I hope you enjoyed the third episode. As mentioned this was going to cover way too much and I had to leave quite a bit out to accommodate this topic. A shoutout to Sistory History who did a promo swap – check out their podcast. Don’t forget you can contact me directly (and if you fancy learn a bit about me).

Maps.

Below is a good map which outlines some of the locations discussed in the episode. You can see Morgantina and Palike.

Image from Juliana Figueira da Hora (see reading list).

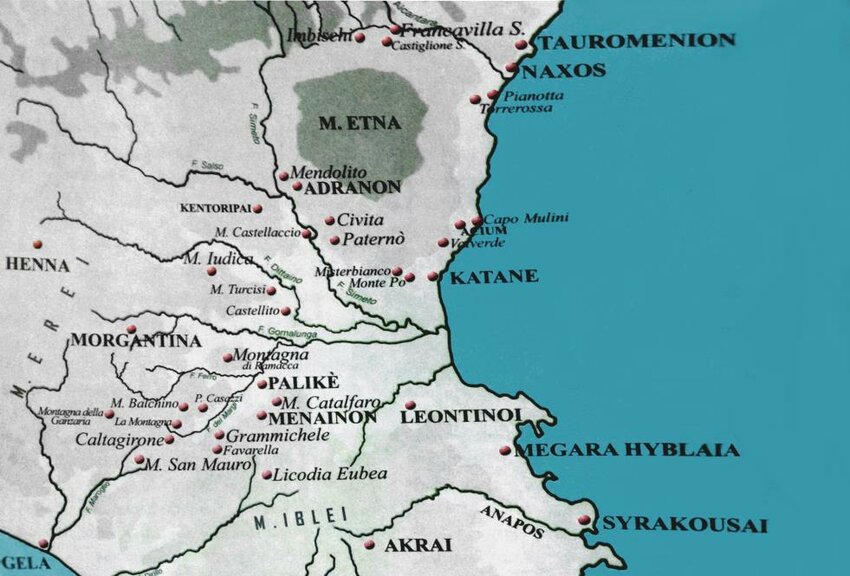

Below is another good map which helps give a wider perspective. It dates to a little after the dates in the episode but the info is still valid. It even has a potential site for Inessa marked on it, you can get an idea of just how Ducetius was marking out his zone of control in the central eastern inlands of Sicily.

Ducetius, Palici & Morgantina.

The Palici (or Palikoi) were local deities as mentioned in the episode. I could have gone into them much more but infortunately didn’t have the time within the episode. JH Croon’s work in the reading list is worth a read.

I mentioned the coin from Morgantina which predated Ducetius and dated to 465 BC. Here it is. If you like coins why not check out a recent blog piece?

As for Morgatina, the below image shows the later development in the foreground with the older settlement (Cittadella) on the hill in the background. It’s likely that Ducetius sacked the Citadella and then the later developments came after he had left Sicily.

Reading list / sources used.

Aristole, Politics.

Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica.

Cartledge, P. Democracy.

Croon, JH. The Palici and autochthonous cult in ancient Sicily.

Da Hora, J. Ducetius: A Sicilian oikista tyrant.

Lentini, Pakkanen, Sarris. Naxos of Sicily in the 5th century BC: New research.

Lloyd, J. Sikel Political Organization to the End of the Fifth Century.

Morakis, A. Ducetius and the relations between Greeks and natives in the Fifth century BC.

Robinson, E. Democracy in Syracuse.

Shepherd, G. Archaeology and Ethnicity. Untangling Identities in Western Greece.

Democracy & Ducetius, transcription.

With a tyrant gone at Syracuse what would happen next? Well, there was civil unrest, the rise of a rebellion and a democratic plant-based process. Join me as I unpack the events on Sicily in the mid-5th century BC on the Ancient History Hound podcast.

Hi and welcome, my name’s Neil and in this episode I’m continuing my miniseries on ancient Sicily with a look at what happened after the fall of those tyrants at Sicily in the 460s and then taking it through to the 440s.

Before I start, the standard fare which I’m sure you are familiar with by now. Please review and rate wherever you can. I’ve been slowly accumulating some great reviews lately, as mentioned before I don’t monetise this podcast – the only thing I ever ask for is for you to help spread the word. There will be episode notes with maps, images and such and including a transcription on ancientblogger.com.

You can find me on X, TikTok, Instagram and YouTube as ancientblogger, all ancient history content btw. This podcast is also on X as @houndancient. I’ve also recently created a subreddit on, well, reddit called Ancient History Hound. You can find my content on there as well.

One final thing and I’ve mentioned this in previous episodes – I’ll continue to refer to the native people on Sicily as Sicilians. You’ll often hear Sicels, Sicanians and Elymians used to refer to separate indigenous ethnic groups. It is useful in a sense as these help differentiate from the Greeks and Carthaginians on the island. But there is debate as to how accurate these are. In any case, if you hear me say Sicilians you know I mean that diverse group of people who were there before the Greeks and Carthaginians.

Ok, then let’s begin.

Assuming you listened right to the end of episode two on the tyrants you’ll have heard me state that in the next episode I’d be including a character who was afraid of getting his hair cut. I’m going to apologise as I won’t be getting to this character just yet. When I came to research and write this episode I naively thought I could cover a couple of major events and then get to the whole haircut anecdote in a single episode.

But reality bites – there was no way I could break down and get into the two main events and everything else in one episode. In fact, these two main events required separate episodes, the first of which you are listening to now. It’s also the reason why this episode covers a relatively short period, starting in 467 BC and finishing around 440 BC.

To get some context and understand where this episode fits I need to give a short summary of where we are. In the 6th century BC, the Greek colonies or cities on Sicily started to generate tyrants. These affected the whole of Sicily in several ways. For example, the competitive nature of them witnessed expansion at the expense of the Sicilians.

In the early 5th century BC tyrants at Gela had come to control much of the eastern third of Sicily. One tyrant, Gelon captured Syracuse and from this point it became the main player in Sicily, at least from a Greek perspective. The competition between tyrants exploded in 480 BC when a fallout between two of them caused a Carthaginian army to become involved. This resulted in the Battle of Himera which was framed by Diodorus Siculus as a confrontation between Carthage and the Greeks which mirrored that of the mainland Greeks against the Persians.

The reality was far from this bombastic narrative. True a large Carthaginian force had been defeated but, as Herodotus reported, the reason they were there was to provide backup for one Greek tyrant against another. This wasn’t exactly as Diodorus had set it out to be. But then Diodorus, like many historians and writers of antiquity, shaped the narrative in accordance with their world view and biases. Diodorus was a Sicilian and though he used earlier sources we should always take into account that he could reframe events to suit his interpretation. Diodorus is the main source I’ll be using here btw.

When Gelon died his brother Hieron had taken over at Syracuse. An action taken by Hieron which factors in this episode was the founding of a new city, Aetna. Though technically true it was really the case of taking the existing colony of Catana, extending its borders, filling it with those loyal to Hieron, whilst removing large numbers of the population there and calling it Aetna. Hieron’s rationale was to provide himself with a loyal base near to Syracuse and to achieve the status of a founder which was a big thing in the Greek world.

In 467 BC Hieron died and power passed to his brother Thrasybulus, and he’s depicted by Diodorus as the epitome of the villainous tyrant, cruel, oppressive and everything else you’d expect. Given that he lived near a volcano Diodorus missed a trick in him not having a lair within it.

Perhaps this was the case, perhaps not, as mentioned in the previous episode and it will form the content of a minisode on tyrants a tyrant wasn’t always a pernicious creature. Anyway, that aside the account of Diodorus and a comment by Aristotle points to the downfall of Thrasybulus after less than a year. Exactly why the people revolted against Thrasybulus might be because he was, as Diodorus painted him to be. It might also have been because tyrants often spent a lot of time shoring up their power base and keeping it so. When one died the new tyrant was often highly vulnerable. It didn’t follow that people who had been loyal to the old tyrant would throw their lot in with the new one.

What we do know is that the revolt wasn’t just from one demographic, the poor. Aristotle noted that those around him and even members of his own family decided that they had had it with tyrants. In 466 BC Syracuse was a place of civil revolt. On one side was Thrasybulus and his supporters, mainly mercenaries. On the other side was everyone else, let’s call them the Syracusans for sake of ease. Understandably the Syracusans realised that they were opposing a very dangerous group, especially as those mercenaries were skilled fighters. Keen to address the balance they put a call out across Sicily for help.

This was answered with cavalry and soldiers coming from Gela, Acragas, Selinus, Himera. It wasn’t just Greeks, even local Sicilians joined against the tyrant.

It’s tempting to view this response by the other Greek cities as indicative of a sense of loyalty. But perhaps there was something else going on here. Syracuse was the dominant power and had achieved this position through a series of tyrants. The other Greek cities may have reasoned that by ending tyranny the power of Syracuse might be nullified. A weakened Syracuse, versus one with a new tyrant, would certainly serve them better.

Eventually the Syracusans won. Thrasybulus made the rare choice of a tyrant, that is the smart one. He agreed to leave the city and retire to Locri. Which he did.

Following this Syracuse established a democracy, I’ll get to this shortly. But peace didn’t last long. Tensions now grew between two groups in Syracuse. The first was the newer citizens, those given citizenship under the tyrants. This was a common tactic which I’ve touched on in episode 2. In order to retain a stable base of support it was a good idea to cram your city with those who were now obliged to you in some way.

The second group were those families who had been in place prior to the tyrants taking hold at Syracuse. This group had suspicions about the newer arrivals. Were they really committed to a democracy? Or might they have loyalties which could lead to another. Also be sure to add in good old-fashioned snobbery. As such they proposed that the offices of state could only be open to those older families. You might imagine how this went down. Badly. It’s true that some of the newer families may have sided with Thrasybulus or supported him. But there would have been those who didn’t. What resulted was another sequence of infighting which was to last up to around 460 BC.

Or at least that’s what Diodorus says happened. His narrative of these events seems blurry, and it has been argued that Thrasybulus hung round for a bit longer and that this round of infighting was simply round 2. In any case by 460 it seems to have been over with the older families winning. Finally, you might think, a chance for everyone to put their feet up. But you know that wasn’t likely to happen. Into this mix stepped another character who will form much of the rest of the episode. Not a faction within Syracuse, a tyrant or even a Greek. Instead, it’s the chance to discuss Ducetius, a Sicilian who was to launch his own power grab on Sicily.

Little is known about Ducetius as most of our knowledge about him comes from Diodorus Siculus. It’s stated that he was from a well-known family and so was presumably educated accordingly. His emergence as a political and military threat dovetails with the fall of the tyrants of Syracuse and so it’s logical to assume that the political space which they left and the ongoing issues at Syracuse following this allowed Ducetius to make his move.

Ducetius was based in the central eastern inlands of Sicily and when Hieron had founded Aetna the assumption is that lands which had belonged to the locals was taken. Not that Hieron or any of the tyrants had been friends of the Sicilians to any great extent. As you just heard they joined in with Syracuse in opposing Thrasybulus.

Aetna, which had been populated largely by Hieron with mercenaries and his supporters now looked highly vulnerable and Ducetius made to move against it. But they were joined by Syracuse which had its own reasons for an alliance. Syracuse had spent several years fighting the supporters of their own tyrant and just north of them was this city populated with pretty much that same demographic. Perhaps this demographic had supported the unrest at Syracuse? Even if not they still presented a possible threat. It may also have been that Syracuse feared what might happen if Ducetius and his local forces took Aetna and became new neighbours. In any case the two forces allied and captured Aetna.

Before I get to what happened after the fall of Aetna here are some words from the Sistory History Podcast. Just so you know this isn’t paid promotion, I’m doing a promo swap with them and thought you might be interested in their podcast.

Thanks to the Sistory History, although after listening to that I am reminded how I sorely need to up my promo game.

Right, back to Aetna and to the ‘what next’.

Following their defeat those at Aetna were moved to Inessa, and this they renamed as Aetna. I know, all the options they could have chosen. The site previously known as Aetna then reverted to its original name of Catana. It wasn’t just the name though, the previous residents, forced out under Hieron, returned. They found his tomb there and smashed it to pieces.

Elsewhere there were changes in the Greek cities on Sicily. The sons of Anaxilas, a tyrant who had ruled Messina were kicked out. In other Greek settlements and cities on Sicily there was a sort of mass reset with those who had been moved out due to political pressure moving back in and taking back what was theirs.

Of course, this all sounds very simplistic and asks more questions than it answers. What was returned exactly and to whom? Syracuse had endured years of civil unrest struggling with this problem. Yet elsewhere this was achieved without much hassle? Of course, Diodorus may have been sketching the very basics of what went on without going into the detail. We have to remember that his history needed to entertain and perhaps the various instances and manifestations of what went on were a bit dry for the audience.

Diodorus was a bit more detailed with the goings on back at Syracuse. The democracy was in place though it’s unclear what exact species of democracy this was. Aristotle commented that it wasn’t until later in the 5th century when Syracuse became a democracy. Yet there were instances which I will come to where we can detect the signs of a democracy in action at Syracuse. So what was Aristotle saying exactly? One argument has it that when Aristotle wrote this he meant that it had become more of a standard democracy following some reforms made later that century. If so then we may just be splitting hairs as it wasn’t just Diodorus who paints a democratic Syracuse. In the next episode you’ll hear how Thucydides describe what seemed to be an active democracy in action.

I now come back to Ducetius and his campaigns in Sicily. An easy trap to fall into would be interpreting Ducetius as some ‘Braveheart-esque’ rebel leader intent on unifying Sicily and fighting back against the Greeks. It’s certainly true that Greek-Sicilian interactions had been getting more tempestuous, particularly with the rise of the tyrants who were happy to take their lands. However, Ducetius had his own agenda and as you will see this would also see him face off against his fellow Sicilians. It’s more plausible to think of Ducetius as a leader who was consolidating power amongst the Sicilian towns in that eastern central region and doing it with both carrot and stick.

After his attack on Catana or Aetna as it was then known Ducetius refounded his hometown of Menae on the plain of Catana. Here Diodorus referred to him as a king, but this title isn’t afforded to him again. Instead, he’s labelled as ruler or leader thereafter. This could be read as Diodorus not being fully sure of what Ducetius was exactly. He was in charge, but of what and what did that make him exactly!

Whatever he was in charge of and however it functioned Ducetius was to bring it against another settlement in 459 BC. This time it wasn’t a coastal Greek settlement but a Sicilian one further inland.

Morgantina was a famous Sicilian settlement which dated back centuries. Initially the settlement was based on a hill, known as Citadella. Greek influence had spread there from the 7th century BC. In the 6th century BC this extended to the adoption of Greek architecture and pottery. Morgantina may have been Sicilian, but a Greek visitor might recognise familiar structures and even the odd voice. Those outside of Morgantina could witness this through their coinage. A litra coin, dating to the mid-460s, so prior to Ducetius, had an ear of grain on one side and the profile of a man with a beard on the other. The lettering on the coin was Greek.

In the mid-5th century, the older settlement was abandoned, or perhaps destroyed and a new one fashioned on Sierra Orlando. The new layout seems to have been influenced by how the Greeks were doing it. This new build may have been after Ducetius had stormed Morgantina and was possibly done by a Greek city. Perhaps Ducetius attacked Morgantina because of its Greek leanings, but that seems a whimsical reason. It’s more likely that he was striking out and increasing his power base in the eastern central lands of Sicily.

After the success at Morgantina Ducetius doesn’t get mentioned by Diodorus for several years. But we do hear from him, though not before there’s yet more political instability back at Syracuse.

In 454 there was an attempted coup by a character called Tyndarides. Diodorus depicts him as using the tried and tested ‘How to become a Tyrant’ route to power. Namely, gain acclaim with the poor and seek to accrue a personal bodyguard. However, this failed, and he was put on trial and executed.

Following this Syracuse put in place a process which had been used at Athens to mitigate a character rising to seize too much political power. The exact conditions a tyrant might emerge from. This was ostracism, albeit with Syracusan twist. Replacing the pottery sherds upon which the names of potential candidates for exile were written they used olive leaves. As a result, they called it Petalism.

Ostracism is a feature of ancient Greece which is well known, or at least the word is. The irony is that it wasn’t common.

There’s much of it, which is debated, for example, when was it put into place exactly? I cover this and much more in an episode specifically on ostracism. But in the context of this episode, we might think of ostracism as a check against tyrants. This was particularly important at Athens after the introduction of democracy or the early form of it in the late 6th century BC where such a situation might have occurred.

The idea was simple, each year a vote was taken as to whether an ostracism was required and if so a vote was taken a few months later. Even then there was a number of votes required to legitimise the result which, if successful would involve that person being exiled for 10 years. Syracuse employed this process but changed a few bits. As mentioned there was the name but there was also the duration if you were exiled you only got 5 years.

Unlike at Athens were it lasted several decades; at Syracuse it was a short-lived affair. Diodorus noted that the problem was that Syracuse was losing too many people to exile. Worst still with the exile of all of these rich and obviously intelligent men the democracy had fallen into the hands of demagogues and ruffians employing gutter politics. Note the sarcasm there. There are a couple of comments to make about this. The first is that this sounds exactly like the sort of criticisms made against active democracies. And here I can point to the comment made earlier about how we think that Syracuse had that type of active democracy long before the end of the century.

For the second point I need to pick up that sarcasm again because this comes across as very snobby. Naturally the rich nobles were all excellent persons, not a bad one amongst them. It may have been true that Petalism had upset the political balance but perhaps Diodorus was showing his own bias here.

A year after the failed coup we hear of Ducetius again. He hadn’t been idle and Diodorus referred to a Sicilian Federation now under his control. The exact nature of this federation isn’t clear and herein runs the danger of Diodorus using a term which didn’t accurately describe the nature of what Ducetius had formed. It’s plausible that Diodorus didn’t have the source material which he could accurately map out the nature of this organisation. In a way it follows his uncertainty in what to call Ducetius when referring to him earlier as a king, then a ruler.

We might speculate further on the composition of this federation. Was it formed of obliging towns and settlements or were some added to it who had little choice. I make this point purely to extend on one made earlier. Namely that Ducetius wasn’t necessarily a Sicilian Braveheart, more likely another political player who was operating with a different resource base but intent on extending his territory.

It was in 453 BC that Ducetius founded a city, Palike. This wasn’t random, it was next to a sanctuary to the Palici who were worshipped by the Sicilians. The Palici were a pair of deities linked to the underworld. More specifically they were linked to the hot waters found nearby. Locals would swear oaths at this location. By founding a city there Ducetius was confirming his Sicilian credentials. The Palici had been on the radar of Hieron, the tyrant of Syracuse. When he founded Aetna he had Aeschylus write a play to be performed there. Though it hasn’t survived the fragments which have, and other commentary indicate that the Palici were involved in the main plot. It’s been argued that Hieron was trying to bring them into the Greek pantheon.

In 452 BC Ducetius captured Aetna. But not the original Aetna which had reverted back to its name of Catana. This was the settlement of Inessa which had been resettled following the success of Ducetius and Syracuse and renamed Aetna. The exact location of Inessa hasn’t been found but it’s mentioned by Thucydides as between Catana and Centuripe. Ducetius’ was pushing his boundaries in more than one sense and Syracuse must have wondered not if but when they’d have to deal directly with him.

As it turned out, they didn’t have long to wait.

In 451 BC Ducetius attacked Motyum. Just in case that sounds familiar, it’s not Motya, the Carthaginian city on the western end of Sicily. This was a small settlement with a garrison from Acragas. As such its thought to have been located near to this Greek city. Where Inessa, or Aetna, had been to the east this was further west. We can now understand this as a push to the west in terms of Ducetius extending his territory. This was the first incursion by Ducetius against a Greek city and Acragas called for help from Syracuse. Syracuse, perhaps realising that it was paying for that necessary decision made in 460 BC heard the call and sent troops. The Greeks and Ducetius clashed and when it was over Ducetius had won the day.

This seems to have shocked the Greeks. Syracuse went as far as executing the general in charge of their troops upon suspicion that he had been bribed. This wasn’t that unusual in terms of a practice; generals weren’t often executed by the Greeks, but they were held accountable, and this is another indicator that there was an active democracy in place at Syracuse. In fact, in the next episode, we’ll hear of one general who was very concerned about what might happen if he returned to Athens having failed.

The success of Ducetius was short lived. A year later he was beaten at Nomai, another unknown location but likely in the same area as Motyum. With his army dissolving around him Ducetius was forced to make a run for his life. The obvious place would be to return to the Sicilian interior where he had been building that support. I mentioned this in episode 1 but just so you know the Greeks had settled largely on the coast of Sicily. True there were some sub-colonies established more inland but these were there largely to secure trading routes to that interior as well as mark out territory. Amongst the hills there Ducetius could lick his wounds and plan. That would be the sensible option. But Ducetius did the exact opposite and dashed to Syracuse.

When he arrived, he made for the altars and declared himself a supplicant of Syracuse. The strategy here was that Ducetius was appealing to a Greek fundamental belief, that of being a supplicant and the possible safety it afforded you.

Supplication can be thought of as a ritual where you place yourself at the mercy of a person or, in this case, a city. You may have heard of it elsewhere in Greek culture, be it in a poem or a play. This was an important ritual which was duly respected by the Greeks. By performing this action he had escaped being made a prisoner on the battlefield, a fugitive who might easily be done away with.

Now the treatment of him might impinge upon the religious mores of Syracuse and they had to consider him within this context. A debate was called.

Killing Ducetius might now displease the gods and bring a stain on the city. So, a compromise was reached. He was exiled to Corinth, the parent city of Syracuse, where he could live out his days. Or at least that was the plan. His exile only lasted a couple of years, in 448 he was back. This time as the founder of another city on Sicily. On the northern shore of Sicily, the settlement of Kale Acte was founded, and this has been argued as modern day Caronia. Ducetius’ desire to settle here was given as the result of an oracle he’d received. However, this feels at best a cover story.

Given that he arrived with colonists and other support this wasn’t an escape from Corinth. No nighttime escape aboard a merchant ship in disguise. What seems most plausible is that he was returned to Sicily with the backing of Corinth and Syracuse and with a specific job, to found a new city. Why was this though? Well, we can only avail ourselves to speculation but there is a thread of logic which can be found here and it starts way back when Syracuse first allied with Ducetius in 460.

Remember that at the outset they had been allies and that alliance had benefitted both parties. After this Ducetius hadn’t bothered Syracuse much at all. The closest he’d come was taking that settlement renamed Aetna, the one which was previously Inessa. Yes, this was closer to Syracuse than it might like but it was still within reason. The following actions undertaken by Ducetius had been to the west, not on Syracuse’s doorstep.

Consider also what Ducetius did after he was defeated. His rationale to arrive at Syracuse might have been seen as outrageous. Why not seek the safety of the Sicilian interior. Well, perhaps it wasn’t that safe. Perhaps the power base he built there was fragile and with this defeat he realised that he was a marked man wherever he might go. Best then to risk it with Syracuse where he might plead with them as to him not being a direct enemy. Syracuse was a democracy so perhaps he had support there.

We can speculate further. Perhaps the deal struck with Syracuse and Corinth involved him returning at some point to found a colony with the knowledge that he could be a useful ally on the island. True, his power base had gone. We don’t know though if there had been tensions within the Sicilian interior following his defeat and his return might act on these to bring support back to him. Founding a city would benefit Syracuse and Corinth. It would also be highly valuable to have a popular Sicilian leader allied to them.

This is all speculation, but it does form a coherent policy. It allowed Syracuse to control some of the Sicilian population and this was an important issue. In Episode 2 I mentioned how Camarina, a sub-colony of Syracuse, had risen against it. The reason for this we are told was the sub-colony allying with Sicilians against its parent city.

All of this might have looked good but it didn’t go down well with one Greek city on the island. Acragas was seething. Not only had Syracuse let Ducetius live when they had him in their grasp he was now back and presumably with the blessing of Syracuse. They had not only failed to exact justice on Ducetius, but Syracuse was now using him to advance their political position. It’s easy to see why Acragas was so angry. The result was a battle fought at the Himera river between Syracuse and Acragas. Diodorus wrote that other Greeks cities joined in on either side, but sadly doesn’t mention which ones. It was a furious engagement with Syracuse emerging victorious.

Ducetius, with his colony founded, seems to have made a bid for power amongst the Sicilians once more. Perhaps this was part of the deal with Ducetius allowed to return to Sicily, found a city and then move back to his heartlands where he could act as an ally to Syracuse. Perhaps Syracuse had been duped and Ducetius had decided that he had unfinished business. His next action would answer the question, but it never came to be. In 440 BC he fell ill and died.

So ended the life of Ducetius. Ducetius provides a unique character and perspective on ancient Sicily. The view and motivation from a Sicilian. It’s a great shame that we don’t know more about him. As ever, perhaps one day we’ll come across something which fills the gaps and adds some flesh to this intriguing character.

And with that I come to the end of this episode. In the next episode I can promise you more tales of mainland Greek city states getting involved in Sicilian business once more. This time on a much larger scale with disaster and misfortune in tow. The Athenian Expedition to Sicily is a story in itself and one I’ll be unpicking. Make sure you subscribe to avoid missing out.

More importantly until then keep well and stay safe.