Lovers in Arms.

The story of how Athens formed its democracy is a complex one, it’s a tale of tyrants, opportunists and unlikely allies (I recorded an episode on Archaic Athens and Democracy for my podcast if you want a wider and more in-depth discussion). One story which was linked to the foundation of democracy there became famous and celebrated. It was a daring heroic act involving two individuals, Harmodius and Aristogeiton. Otherwise known as the Tyrannicides.

So it goes that the pair, intent on freeing Athens from the tyrant Hippias, assassinated the tyrant’s brother in 514 BC and this act led to Athens securing its freedom in the form of democracy. Neither lived to see this though, Harmodius was killed on the spot with Aristogeiton caught shortly after and then executed.

The Tyrannicides acclaimed.

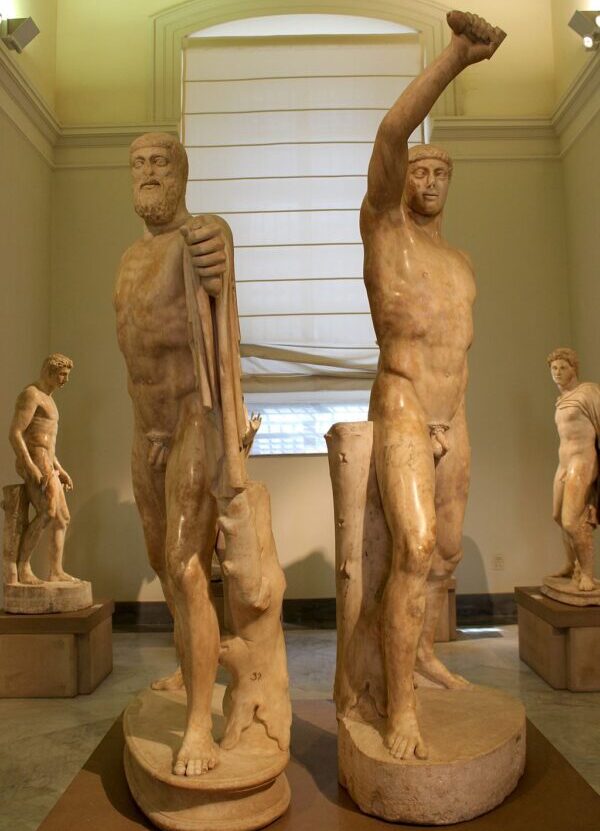

The pair were feted in antiquity, at least in Athens. There were drinking songs, a cult established and famously a statue of them. This was set in the Athenian Agora, no mean feat in itself as the duo became the first mortals with a statue honoured in this very important space. When the Persians sacked Athens they took the statue, but it was quickly replaced. Around 477 BC a new bronze statue was set, again in the Agora. It’s this one which the later famous Roman copy was based on.

A statue base thought to have been the one which held the statues provides further insight into how Athens understood the pair, or the narrative behind them. It’s associated to Simonides and reads:

“Truly, a great light dawned for the Athenians when Aristogeiton and Harmodius killed Hipparchus…the pair made their native land equal in the law.”

The epigram neatly captures the narrative which was strongly pushed in 5th century BC Athens. That the Tyrannicides were crucial in both freeing Athens from harm and helping to establish democracy. However, as good and dramatic a story as it undoubtedly was – how much of it was true?

The truth of the Tyrannicides.

Large scale political or social changes are complex and formed of many small moving parts. In some instances a minor event assumes a much weightier position. Usually this minor event has a symbolism behind it which is far easier to frame a story around than to get into the smaller nuances. Take the storming of the Bastille, a pivotal episode in the French Revolution (France even names its national day after this). Though it undoubtedly happened the storming of the Bastile wasn’t exactly a cornerstone event in the French Revolution. As a small moving part, it did very little to move France to a Republic. But it’s a great symbolic story to tell.

The tale of the Tyrannicides is one earlier example of this, and this isn’t due to some recent arguments made by scholar. The 5th century BC Athenian historian Thucydides took great swipes at the narrative developed by Athens about its democratic heroes. Indeed, he begins his deconstruction of this narrative by writing that “the Athenians themselves are no better than other people at producing accurate information about their dictators and the facts of their own history” (History of the Peloponnesian War. 6.54ff). Ouch.

Thucydides continued to correct the record. The assassination of Hipparchus (the brother of the tyrant Hippias) wasn’t a political act but an act of revenge for an insult made by Hipparchus to Harmodius. This itself was due to Hipparchus making romantic overtures to Harmodius who resisted (he was in a relationship with Aristogeiton).

When the pair made their fateful move upon Hipparchus it was nothing to do with moving the political needle towards democracy. It was about honour and settling scores amongst nobles. It also explains the awkward plot hole in what would be the established narrative in which the pair are praised for killing a tyrant, where in fact they killed his brother. It may have been that later versions of their act had Hipparchus as tyrant to try and make sense of this loophole. Thucydides spent time railing at the idea anyone could have reasonably thought Hipparchus as the tyrant. Presumably this was something believed and again, because it made more sense. The Tyrannicides were called so not because they killed the tyrant’s brother.

An unlikely ally.

Even without trying to explain holes in the narrative there is the question of time. Hipparchus was assassinated in 514 BC and the reforms of Cleisthenes didn’t occur till 508 BC. So how could an act several years earlier have a direct path to democracy? Well, in short it didn’t.

But one outcome of the assassination was to drive Hippias from being a relatively modest tyrant to a paranoid and increasingly pernicious one. In 510 BC he was finally driven from Athens and, shock horror, by Sparta. Exactly what drove the Spartan king Cleomenes to help drive Hippias from Athens is commented on by Herodotus. In his Histories he reported a rumour that the Oracle of Delphi had been bribed (Hist.5.62). Whenever a Spartan sought an oracle there they would be told, in a manner, that Hippias needed to be removed.

The Spartans were highly pious, so the influence of the Oracle seems to have worked and so Sparta forced Hippias from Athens. However, that still leaves us with the individual behind all of this. Perhaps not so much an individual but a family. The Alcmaeonidae were an old and powerful Athenian family who were largely in exile at the time. They had won the contract to build a temple at Delphi and decided to go above and beyond in what was costed and agreed, better materials were used including a façade of Parian marble. The cost of these extras were not charged.

Cleisthenes and his reforms of 508 BC.

The Alcmaeonidae included one famous son at that time, Cleisthenes. He’d been an active politician and so we might play the cynic here and consider the political long game in effect. To help create a political space for their return his family had bribed or given a favour to Delphi in order that they might influence Sparta to remove Hippias. If this was the plan it worked perfectly, though when he arrived back in Athens Cleisthenes still had his work cut out. Ironically, he came up against Isagoras as the two fought for control of Athens. Isagoras was backed by Sparta. If nothing this incident sums up the manner of Greek City State politics perfectly. Allies and enemies were terms which could have a very short shelf life.

By 508 BC Cleisthenes had won the political battle and his reforms took hold. The Tyrannicides could be reinvented as founder heroes of the new political system taking root. Their story encapsulated much of what a founding myth needed, the self-sacrifice for example. It’s just that a few loopholes needed attending to (perhaps why it seems to have been thought by some that Hipparchus was the tyrant). As a founding myth it held great symbolism, the heroic pair prepared to lose their lives (and did) by standing up to tyranny and an undemocratic system. It was perhaps a neat metaphor for Athens which itself was now having to deal with navigating its place in the Greek world with its new political system.

Oh, and of course it completely removed the involvement of the Spartans, which I can’t imagine was an unpopular thing.

(For more reading on Cleisthenes and all of this check out the episode notes page for the Archaic Athens and Democracy episode).