In the recent Gladiator II film, much has been made about the naval battle in the Colosseum. Did this really happen and what about those sharks? Well let’s look at both elements and ancient Greece as well.

Sharks and the Mediterranean.

The Mediterranean is home to approximately 73 shark species (according to the Blue Marine Foundation). Many of these might be unsurprising, the dogfish for example. Others might raise an eyebrow, the Great White and hammerhead (the former being critically endangered) . In the film the tiger shark features, albeit in CGI form and there is some debate as to whether this species is a resident of the Mediterranean or just an occasional visitor. In 2015 a juvenile pair were caught off the coast of Libya (read here for more on this). This raised questions as to whether the mother of these was a resident of the Mediterranean or simply passing through as has been thought. Though there is no clear answer yet what can be concluded is that if tiger sharks are residents we have no substantial evidence (yet) of this.

However, we have plenty of evidence of sharks in the Mediterranean going back a long, long time.

Shark BC.

Though the shark is aquatic by nature fossilised shark teeth have been discovered on mainland Europe which date back to the Pliocene period (5.3 to 2.5 million years ago). Adrienne Mayor noted that there’s evidence of teeth dating to the Miocene period being used on sacred sites on Malta dating to the 4th millenium BC. Shark teeth were thought to be used by Maltese potters to effect distinct grooves on bowls which date between 2500-1500 BC.

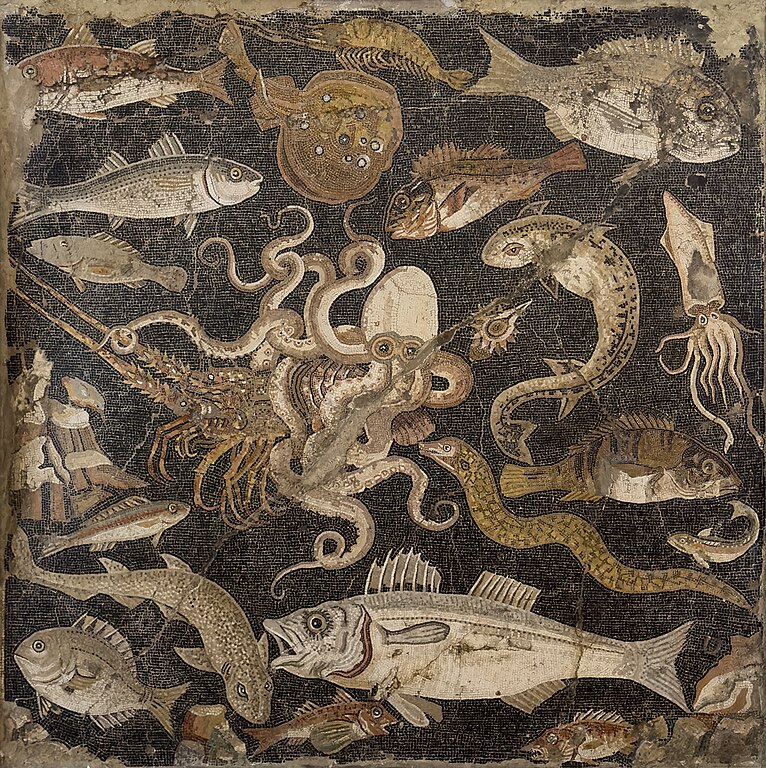

We can see shark species depicted on this mosaic from Pompeii which dates to the early 1st century BC. In the lower left section a dogfish can be made out.

Pliny and Pithekoussai.

Unsurprisingly Pliny commented on the shark in his Natural History. He didn’t refer to them as sharks, instead he used the name ‘canicula’ (dog fish or sea-dog) to refer to sharks more widely. His entry about these indicated how much they were feared:

The divers, however, have terrible combats with the dogfish, which attack with avidity the groin, the heels, and all the whiter parts of the body. The only means of ensuring safety, is to go boldly to meet them, and so, by taking the initiative, strike them with alarm: for, in fact, this animal is just as frightened at man, as man is at it; and they are on quite an equal footing when beneath the water. But the moment the diver has reached the surface, the danger is much more imminent; for he loses the power of boldly meeting his adversary while he is endeavouring to make his way out of the water, and his only chance of safety is in his companions, who draw him along by a cord that is fastened under his shoulders. (Pliny NH 9.70).

The concept of danger below the surface had been noted as far back as Herodotus (6.44). Before they arrived at Marathon in 490 BC the Persian naval commander Mardonius had suffered from a storm near Athos. This was a peninsula in the north of the Aegean Sea and here ships were wrecked with sailors drowning and being eaten by the numerous sea monsters which Herodotus had reported as living there. It’s highly plausible that sharks would have been involved.

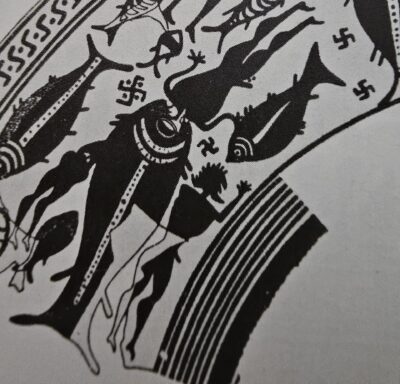

In the context of art and the shark we can move to something of a speculative image. The Shipwreck Crater dates to the end of the 8th century BC and was found at Pithekoussai (you may recognise this place from a previous post). The crater is decorated with a depiction of a shipwreck.

The imagery on the crater has been reproduced as a drawing and alongside several fish and the upside down ship there’s what seems to be a person with its head in the mouth of a large fish.

As with any image there’s always a danger in taking it too literally. Perhaps here the artist was simply using the size of the fish to add drama (including the fate of the drowned which I detail below), or possibly because they had heard stories of large fish in the Mediterranean? That it specifically evidences a shark attack is one of many alternate readings.

Of course it might be to offer a wider and more horrifying comment – that those drowned would serve as food for sea creatures. This outcome would mean no proper burial of the deceased and with that no chance to progress through the Underworld. This was a substantial fear for the ancient Greek and we might remember the fate of poor Arestopaeus who fell to Achilles as he fought in the river Scamander in Homer’s Iliad. After being killed the poet described how his corpse was left for eels and fish to nibble on. For a seafaring people the awfulrealisation of drowning and your body not being recovered was echoed in the opening speech by Polydorus in Euripides’ Hecuba. He addressed the audience as a ghost and one whose body lay bobbing in the sea after his cruel murder. He described it poignantly as unburied and unwept. Think also of the fate of the Athenian generals after the naval battle of Arginusae in 406 BC. They had failed to recover the bodies of those who died during a storm and were executed as a result when they returned to Athens.

Sharks in the Colosseum?

For those who have listened to my Ancient History Hound episode titled Rise of the Gladiator you will know that naval battles were a separate thing from a standard gladiatorial fight. These were naumachia, often staged in an artificial lake or such where non-gladiators would fight each other in a naval setting. A famous instance of this was one under the Roman emperor Claudius in which the criminals fighting greeted him with an oath which has since been erroneously mapped to gladiators as the “we who are about to die” thing you often read. Just to clarify – we have no record of a gladiator every saying this – it was only mentioned once and in the context of a bunch of criminals fighting to death on ships in a naumachia.

Much has been made of the logistics behind using the Colosseum as a location for naumachia. The main issue being that there was a substantial structure underneath the Colosseum which made the prospect of flooding the area above it highly improbable. As ever though there might be some truth that the Colosseum was used – but only for a short time and before the sub-structure under it was built. The website Bad Ancient has a great article on this and concludes that any naumachia at the Colosseum most likely took place in its early years under the emperors Titus (AD 79-81) and Domitian (AD 81-96). Even then each emperor only seems to have used the Colosseum once for a naumachia, the tradition seems to have been that naval battles took place in either artificial basins previously used or new ones.

Further reading:

Mayor, A. The First Fossil Hunters.

The Classical Association of the Middle West and South: Do We Need a Bigger Boat? A Possible Depiction of a Carcharodon carcharias on the Pithekoussai Shipwreck Krater.

Collareta, Casati, Di Cencio & Bainucci. The Deep Past of the White Shark, Carcharodon carcharias, in the Mediterranean Sea: A Synthesis of Its Palaeobiology and Palaeoecology.

Richter, A. Greek Art.