In a recent Ancient History Hound minisode I spoke about a number of gifts which, well, didn’t go so well. Here’s a few instances of gifts from Mesopotamia and Greece which had the sort of outcomes which weren’t expected by the recipient.

Mesopotamia.

We have references to gifts and the situations behind them in cuneiform tablets. Some of these date to the 19th-16th centuries BC (considered the Old Babylonian Period). An individual in one such tablet called Adad-abum asked for a fine string of beads to be worn around the head and I quote:

“I have never before written to you for something precious I wanted. But if you want to be like a father to me get me a fine string full of beads to wear around the head. Seal it with your seal and give it to the carrier of this tablet so that he can bring it to me”.

This is a nice example of a gift being requested, and there’s also a bit of emotional leveraging going on there which I think we have all experienced. However, personal relationships weren’t the only place where gifts were found. On the grand stage they were an important component of what we might think of as international relationships.

Take Zimri-Lim, a ruler of Mari in the 18th century BC which was a city state in modern day Syria. Here was an individual who boasted of being the first to have an ice-house on the Euphrates where ice could be collected from the mountains and kept cool for the summer. A man you might think of good taste, however, one tablet recorded how he sent Hammurabi, the King of Babylon a pair of Cretan boots. These were returned with no reason given. That said it might be worth knowing that in 1762 BC Hammurabi sacked Mari and Zimri-Lim is not heard of again. You can read more about this in a previous article.

In a less dramatic fashion in the Middle Babylonian period, roughly the 16th to 12th centuries BC the King of Cyprus sent an apology to the King of Egypt for the lacking amount of a gift. He could only gift him 500 lbs of copper due to a pestilence which had disrupted copper production on the island. Continuing the trend was the harassment of Takhuli, an ambassador from Ugarit, a city in northern modern-day Syria. He was manhandled by the Hittite King due to the poor quality of lapis lazuli sent there.

Beware of ancient Greeks bearing gifts.

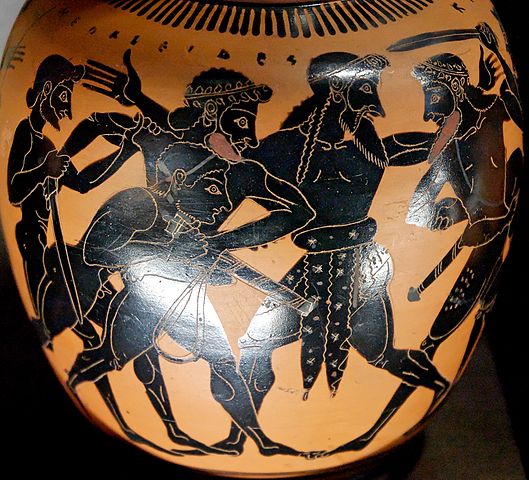

The falling out over gifts was a thing which played a part in one of the most famous works of ancient history. In Homer’s Iliad the hero Achilles sulks from battle because Agamemnon has taken a slave girl called Briseis from him. Eventually Agamemnon realises his error and makes a substantial offer to Achilles, bars of gold, tripods, cauldrons, horses, slaves and when Troy is taken a choice share of more or less everything. But this is refused, and the reason Achilles rejects this over-generous offer reveals how the Greeks might view gifts, as something which reflects status. Something between equals. It’s argued that the initial act of Agamemnon relegated him to something less than an equal in the eyes of Achilles, as such gifts from him are not what might repair the situation because Achilles doesn’t see Agamemnon in that way anymore, he’s not an equal to him and therefore the gifts are largely, well not worthless but they don’t have the worth that they should have.

Something we forget about in Homer is his sense of humour and one gift exchange, this time between equals, is a good example. The Greek hero Diomedes, a favourite of mine, meets Glaucus who fought on the side of the Trojans. Before they fight the pair share introductions and then realise that their grandfathers were very good friends. This changes the situation entirely and the two agree not to fight and instead exchange gifts. Homer notes that Zeus had stolen the wits from Glaucus as he swapped his golden gear, which we understand as his armour for the bronze armour of Diomedes. Not a fair trade by any measure.

Gifts amongst nobles were an important way of keeping good relations – at the funeral games of Patroclus these take the form of prizes, and of course being Greeks there are plenty of tantrums. Menelaus throws a spectacular one when he competes in the chariot race and comes behind Antilochus. Possibly the biggest sulk over a lost prize comes in the Odyssey, when he speaks with the dead Odysseus appeals to the shade of Ajax who fell out with him over the armour of Achilles. Will he finally get over it and chat with the one living person who everyone else is clamouring to chat to? Of course not, he just wanders off.

Perhaps I have been a bit unfair with regards to the sulk Ajax was in. In the Odyssey the falling out over the armour and gear of Achilles is referred to as driving Ajax to a tragic end. As mentioned gifts and prizes could be a sort of currency of status and status was incredibly important in the Homeric code. We understand this more in the play by Sophocles in the 5th century BC called Ajax where he is driven to madness partially by the issue over the armour and sadly takes his own life. Another tragedy from the 5th century BC has gifts as an important plot point.

Wedding gifts and love potions.

Medea in the play of the same name by Euripides is able to take revenge on Jason through her actions against his bride to be. It’s an inversion of a norm we see today, wedding gifts in this instance a golden coronet and a dress both items which will have a horrifying outcome for both the bride to be and her father. These are delivered by Medea’s own sons. What’s worth noting here is that the fate of her sons are also part of her revenge against Jason. As such the elements of Medea’s horrifying plans are all present in this act, through the act of gift giving. The wedding gifts which will end the life of the bride to be and her sons taking them who will also fall at her hand later on.

One infamous wedding gift in Greek myth had a similar potency as those of Medea but the effects weren’t as immediate. Harmonia, the goddess of harmony and in particular marital harmony, was the daughter of Ares and Aphrodite. As you might expect, Hephaestus who was Aphrodite’s husband wasn’t exactly happy and when she married Cadmus the legendary founder of Thebes he made her a necklace as a wedding present. Except this wasn’t your everyday necklace, it was cursed and the wearers of it were doomed to suffer calamities and all sorts of bad outcomes a good example being one owner – Jocasta, the mother of Oedipus. It came to be known as the necklace of Harmonia, which feels unfair on Harmonia.

Another gift with a tragic outcome is found in Women of Trachis, a play by Sophocles. This is a gift with a twist and perhaps here the terrifying nature of it was that it was something which members of the audience might themselves have tried or used – a love potion.

The story behind the love potion perhaps held a clue that it wasn’t what it said on the bottle. When Deianeira, the wife of Heracles, was abducted by a centaur called Nessos he was killed by Heracles as you would expect. The item used was an arrow which contained the blood of the hydra smeared on it. As he lay breathing his last Nessos told Deianeira that if she collected the blood from around the arrowhead it could be used as a powerful love potion or in this case a salve to recapture the heart of Heracles.

As you have already guessed this came to be used by Deianeira, but not before she realises her mistake. The fact that Nessos had told her to keep this salve it out of sunlight and not to touch it didn’t ring the alarm bells you think it might have. After dipping some wool in it she spread some on a tunic, a gift, for Heracles. The horrible realisation of the effects of the salve came when she noticed what had happened to the piece of wool involved – when it was exposed to sunlight it crumbled into powder. It’s too late to do anything and Deianeira soon receives the news about Heracles. Whilst making a sacrifice near a pyre the tunic soaked with the supposed love salve began to burn and this sent him into an agonising rage which he couldn’t escape.

The outcome is bad for everyone, racked with guilt Deianeira takes her life and Heracles ends his on a pyre – the only way he can stop the pain. Not wishing to denigrate a demi-god but when I was 10 I got bottle of Old Spice for Christmas and unwittingly decided to try it. Not exactly the same I realise but I am not exactly a demi-god.

My final example of a gift gone wrong is actually one of the most famous gifts in myth gone right. The Trojan horse. I’ll spare you the details as you are probably well acquainted with it but what you might not know is that this doesn’t feature in the Iliad. This poem only takes us up to the death of Hector, so the death of Achilles, the Trojan horse and the sack of Troy comes later in the wider myth of the Trojan War. The horse is mentioned fleetingly in Homer’s Odyssey – we get much of the standard myth of the horse from Virgil, a later Roman poet.

Further reading.

Oppenheim, AL. Letters from Mesopotamia.

Mueller, M. The Language of Reciprocity in Euripides’ Medea.