I hope you enjoyed the episode, what was going to be a two-part episode is becoming an ongoing mini-series on ancient Sicily and I’m really enjoying researching writing and recording it. If you have any feedback get in touch! If you want to have a look at some coins from Himera, Acragas, Selinus and Syracuse you can find my article on them here.

Battle of Cyzicus.

This is where Hermocrates was defeated and was fought off the coast of Cyzicus during a battle which took place in 410 BC. Below is a map of the Sea of Marmara (it’s the lighter blue colour). This connects the Aegean and the Black Sea. I’ve marked up Cyzicus on the other map, it’s on the south coast.

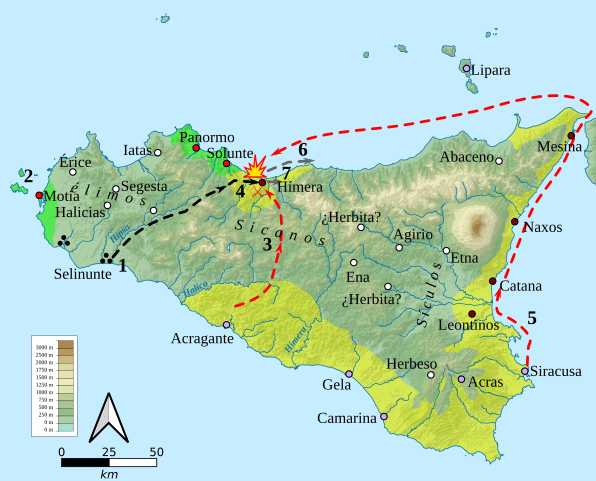

Carthage on campaign in ancient Sicily.

This map plots Hannibal’s movements from Acragas to Himera – the place names aren’t in English but you can hopefully make them out.

Egesta (or Segesta).

Though this was a non-Greek settlement (it was native Sicilian) there was a real sense of Hellenisation there. In fact there is a fantastic temple which was built there around 417 BC.

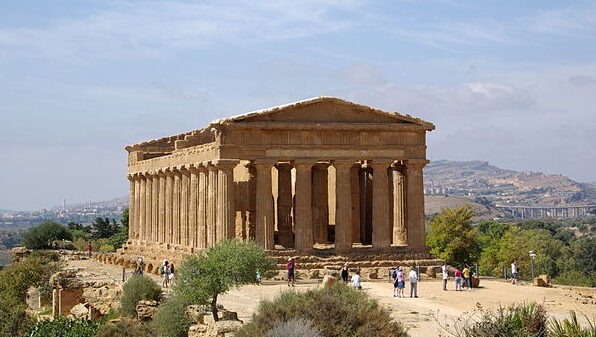

Acragas.

As I mentioned in the episode, Acragas (modern day Agrigento) was wealthy and boasted fine architecture. Below is the so-called tomb of Theron and the Temple of Concordia. The latter was a large Greek temple, its name is taken from a later Roman association it had.

Reading List / Sources used.

Diodorus Siculus

Xeneophon, Hellenica.

Lancel, S. Carthage.

Pilkington, N. An Archaeological History of Carthaginian Imperialism.

ed Smith C & Serrati J, Sicily from Aeneas to Augustus.

ed Tsetskhladze, Greek Colonisation.

Transcription.

Hi and welcome, my name’s Neil and in this episode I’m picking up with what happened at Sicily after the defeat of the Athenian Expedition. In the last episode I ran the rule over the failed attempt by Athens to bring Syracuse to heel. It was a bit of a rollercoaster. If you thought the Greek cities on the island could have a nice cup of tea and a bit of a rest think again. There was a whole heap of trouble coming and that saying about how history repeats itself was to prove horribly true.

Before I go further a big thank you for some of the reviews and comments which have been rolling in. One in particular is worth a mention because it included a great question about why the focus in the episodes were weighted more to the Greeks than the Phoenicians and Sicilians and I want to quickly answer that.

In short it’s to do with the source material we have. The Phoenicians and Sicilians don’t have much in the way of a crafted narrative in the way the Greeks do through the accounts of Herodotus, Thucydides and later Diodorus Siculus.

It would be a dream to have something about the Phoenicians and Sicilians written by one of them and covering accounts of the events of their history. We don’t have that, what we are left with are objects, inscriptions and buildings which require interpretation. It’s still amazing to have these, but a cup, say from a tomb, can only tell us so much. It won’t recall a speech made, provide an account of a battle or simply describe a particular incident which the Greek sources didn’t bother with.

In the first two episodes I did my best to offer some insight into the non-Greeks through what we have found at sites across Sicily. But, simply put, that lack of a textual source is the issue here. I hope that helps answer the question and thanks again for asking.

If you want to leave feedback please do and I can neatly segue into the standard appeal for reviews and ratings which you can leave on Spotify and Apple or whichever platform you use to listen. Aside from that you can get in touch with me via my website ancientblogger.com where there will be notes for this episode. You can also find the Ancient History Hound subreddit on, reddit and twitter with the handle houndancient. There’s also me on TikTok, Instagram, Youtube and X as ancientblogger. It’s all ancient history by the way. Oh, and occasional picture of my dog. If you are truly old school enough for an email there’s ancientblogger@hotmail.com.

Ok then, let’s get to Sicily.

In 413 BC Syracuse had delivered a humiliating defeat to Athens. The Sicilian Expedition had been a wild ride with the likely outcome changing more than once. But at the end it was Athens which lost lots of men, resources and its reputation. Things got even worse than that though. It had indirectly led to Athens breaking the Peace of Nicias and so Sparta was now free to attack Athens directly.

The Sicilian Expedition had occurred because in 416 BC Egesta, or Segesta, a non-Greek city had appealed to Athens for support against the Greek city of Selinus which itself was backed by Syracuse. Though Egesta was non-Greek the central issue here was cities on Sicily inviting overseas elements to help with their internal power struggles. This had been done earlier at Himera in 480 BC, which I’ll mention later. It was such a concern that in 424 BC there had been a conference of the Greek cities on the island at Gela in which they all agreed to not bring in overseas interests. Whilst this was sensible the Greeks missed a trick. I say this because it wasn’t so much the action of a Greek city, or in the case of Egesta a non-Greek city, reaching across the waters for help which was the issue or the problem. It was much more about ensuring that no city felt the need to do so. The old saying about prevention being much better than a cure comes to mind.

I’m not going to say more than that, but the Greeks could have saved themselves a lot, and as you will hear a lot, of bother if they had taken that opportunity to redress that problem. But hindsight is a gift I suppose.

After the defeat of the Athenians the historian Diodorus Siculus described a debate as to what Syracuse should do with the Athenian captives and their commanders. Hermocrates, who you might remember from the previous episode, called for clemency. He seemed to want the soldiers released in part along with the generals. But two men were vehemently against this. Gylippus had been the Spartan general who had been sent to help Syracuse and had worked wonders in its defence. His reasons were of the pragmatic type. Sparta was now at war with Athens so if he could avoid all those soldiers returning all the better. The other was a new character, Diocles.

Little is known about Diocles save for his dedication to reforming Syracuse to make it a more democratic place. His reforms included having experts draft laws and the use of lots to select officials. As such he was widely admired, and one account of his death sums up his dedication to the very laws he had created. One day Diocles heard a commotion in the marketplace and headed there to see what was going on. However, he was wearing a sword and one of the laws which he had brought in forbade this, in fact if you were caught carrying a sword in the marketplace the punishment was death. When this was pointed out by an onlooker with the comment that Diocles was not following his own laws he killed himself on the spot. This may be true, or it may be a tale to underscore the virtuous nature of Diocles, but it tells us something at least how he was perceived

The assembly at Syracuse was swung by the arguments of Gylippus and Diocles and so the Athenian generals met their respective ends, and the Athenian soldiers were enslaved, though there is an anecdote that some were able to buy their freedom if they could quote lines from Euripides. As for Hermocrates, he was promoted to general and sent with some ships to aid Sparta against Athens. Though this sounds like something to celebrate it may have been the opposite and perhaps the work of Diocles who emerges as Hermocrates’ political rival. That’s because by giving him this honour Hermocrates was now away from Syracuse. Added to this was that any general was accountable for their successes and failures. Hermocrates couldn’t cash in on his achievements in helping to defend Syracuse, these couldn’t be used to cover him if he failed in his new role.

Outside of Syracuse a big question now hung over Egesta, what would it do next? Athens, its would be protector, had failed. Worse still Syracuse was triumphant and as a result Selinus could act against it without fear. In 411 BC Egesta found itself in the same situation it had been in 416 BC, alone and needing some backing against Selinus and therefore Syracuse. In 416 BC it had been Athens which it sent an embassy to; this time it looked far closer to home.

Egesta, as you may remember from previous episodes, sat in the west of Sicily. This had traditionally been an area controlled by Phoenicians, primarily through Motya which was the first colony on Sicily which was made by the Phoenicians. But there were also the Phoenician colonies of Panormus, modern day Palermo, and Solunto. As I covered in episode 2 – Tyrants and Tragedy – the Phoenician colony of Carthage captured Motya in the mid-6th century BC. Now Carthage controlled that part of the island.

The Carthaginian corner had largely stayed silent in the affairs of the Greeks, the one notable exception was in 480 BC where it had supplied a force to one Greek tyrant who faced off against another Greek tyrant. This had been the famous Battle of Himera where the Carthaginian force was crushed. As a result, it signed a peace treaty with the Greek tyrant Gelon.

Egesta now sent ambassadors direct to Carthage requesting support. This met with strong approval from one individual there. Hannibal Mago was apparently the grandson of Hamilcar, the Carthaginian general who had fallen at Himera in 480 BC. As the movie-tagline goes, this time it was personal. But why would Carthage consider such an offer? What might their motives be?

Without a Carthaginian source we are left to speculate but there are some good reasons as to why Carthage agreed to lend its support to Egesta. The main being that Egesta was in the region Carthage controlled, the western corner of Sicily. If it fell to Selinus or Syracuse or some Greek power block then it would cause tension. The history of the Greek cities on the island had been couched in expansionism, both at the expense of the native Sicilians and other Greek cities. It would be naïve for Carthage to think that Egesta could fall and if not lead to something bigger further down the line.

Scaffolding this point is that to not do anything might be seen a large indication of weakness. What Carthage perhaps feared is what if the Greek cities stopped squabbling, formed an alliance and decided to push them out of Sicily? Carthage now had the funds to support Egesta and it had a general like Hannibal who was pulling at the lead to do so. An important final point was what Egesta offered which was effectively the city itself in return for protection.

Hannibal immediately set about sourcing a mercenary army with soldiers recruited from Africa and Iberia. With this force he landed at Motya and marched to Selinus, in 409 BC he laid siege to it.

Selinus sent for help and Syracuse assembled a force with the cities of Gela and Acragas waiting so they could join them as one single force. Diodorus Siculus noted that this took some time and perhaps this wasn’t an issue as the Greeks thought they had time on their side to respond. This in part was due to the nature of sieges in the ancient Greek world. These were often drawn-out affairs where one side encircled the city and waited it out. A common tactic would be for the besiegers to appeal to a disgruntled faction inside the city, promising them the power that they were seeking once the city was taken. If this worked then lo and behold a gate would spring open at an opportune moment, or soldiers let in for a sneak attack or a revolt incited which would agree a surrender.

When Selinus fell it didn’t do so to any treachery, it fell because men stormed the walls and managed to take the city far quicker than might be expected, according to Diodorus in a manner of days. The following description by Diodorus is full of despair but also what may be familiar tropes about Carthage by the time he was writing. Diodorus Siculus may have been a Greek born in Sicily in the 1st century BC, but he knew his Roman audience would lap up accounts of Carthaginians being suitable barbaric. As such temples were sacked and disrespected, there was mass slaughter of some 16,000 inhabitants and the dead mutilated. Of course this may have been true, but even if not it would have been a good idea to include. After all, it’s not as if Carthage was going to sue.

According to Diodorus Selinus had stood for 242 years before Hannibal took the city and pulled down its walls leaving it as a broken husk. The effect of this shouldn’t be underestimated. True the tyrant Hieron had reshaped Catana and temporarily named it Aetna. But an entire city destroyed, its inhabitants enslaved or slaughtered. This was something the Greeks hadn’t experienced on Sicily and worse was to come.

Hannibal Mago wasn’t satiated, and his next move took him north to Himera to settle the old score I mentioned earlier. So began the fight for Himera.

At Selinus the tactic had been to try and repel the siege from the walls but here the Greeks decided upon a different strategy. A force from Syracuse led by Diocles combined with the defenders from Himera and took the fight to the Carthaginians outside the city. This took the Carthaginians by surprise and drove them back. However, Hannibal soon regrouped and led a counter charge which at first checked the Greek momentum and was then victorious. The defeated Greek force made it back to the city where they waited for the siege to begin. However, what was to cause the greatest damage wasn’t a siege engine or Carthaginians scrabbling up and over the walls. It was a rumour which spread and caused widespread panic.

The rumour was quite simple; Hannibal wasn’t intending to lay siege to the city. This was a distraction and whilst the Syracusan force was embroiled at Himera a small group of elite soldiers went onboard ships and heading for Syracuse which lay undefended. Like any good rumour it was plausible enough to be believed and the Greeks responded to it as if it were real. Himera was to be abandoned in order that the Syracusan force could return, Diocles commandeered 25 triremes to help with the evacuation. These would shuttle back to pick up the population and move them to a safe distance. In the meantime, a force would be left to defend the walls as best it could and wait to be picked up.

Perhaps those last defenders realised what was going to happen, but perhaps some furtively scanned the horizon for the tops of masts or a prow. But these never came in time. Soon Hannibal took the city of Himera and so began its destruction. Cue the expected stories of brutality. This even extended to 3,000 prisoners being executed by Hannibal’s men at the spot his grandfather had fallen. In a short space of time two important Greek cities on Sicily were practically gone.

By 409 BC the fortunes of the Greeks on Sicily and Carthaginians were in stark contrast. Syracuse had gone from the zenith of defeating Athens outside its walls and more impressively in its Great Harbour to the nadir of retreat and watching an enemy destroy Greek cities which were in a sense under its watch. Just to give some context you might think that this meant all of Greece was at war with Carthage, this wasn’t so. Carthage continued to trade with other Greeks. Pottery from Athens was still being imported and traded whilst all this was going on and it’s another reminder of how complex the nature of Greek city state politics could be.

After completing his victory at Himera Hannibal dispersed his troops and returned to Carthage a hero, his ships sitting low in the water with all the spoils of war from those two rich Greek cities. His successful campaign had left more than gaps in the landscape where cities once stood. It had reset the power dynamic on the island and this itself would have internal consequences at Syracuse as you will hear.

If you scraped the barrel you could find some comfort for the Greeks on Sicily. Hannibal hadn’t pressed his forces more, so they at least had that. Perhaps that was it, a stern lesson for the Greek cities who would be left to lick their wounds for a few generations. They were also not entirely out of the fight and there was at least one individual who was looking to show Carthage that the Greeks still had fight left in them.

When Hermocrates set off as a general to support the Spartans with those ships he’d ended up quite a distance from Sicily. The modern-day sea of Marmara sits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. It was here in 410 BC that a Spartan force which included Hermocrates and his fleet, was defeated by Athens. After the defeat word came from Syracuse that the generals, Hermocrates included, had been exiled, and yes, that was probably the work of Diocles.

Xenophon, a contemporary source, painted a scene of those serving under Hermocrates begging him to stay and not leave. But of course, Hermocrates wouldn’t hear of it, this was the law after all, and Hermocrates would never break the law.

When Hermocrates returned to Sicily he couldn’t enter Syracuse due to his status as an exile. But he could do something. Making his way to the ruins at Selinus he partially rebuilt the fortifications and used it as a base. With around 6,000 troops he started to raid the Carthaginian western area of Sicily.

His next target wasn’t Carthaginian, it was his political enemies back in Syracuse. Hermocrates travelled to Himera where he gathered the bones of those Greeks who had fallen and had them transported to Syracuse for burial by a detachment of his men. This might be considered an act of pious altruism, however, it was much more a political act with an underlying message. When the carts arrived in Syracuse the effect was to undermine those who had been in charge at Himera and who hadn’t afforded the slaughtered Greeks the correct funerary rites. In a sense this seems obvious, after all the whole force had been soundly beaten so there wasn’t the opportunity to do this. However, affording the fallen the necessary rites was always a sensitive subject. During the Peloponnesian War Athens had lost a naval battle at Arginusae and a storm had prevented recovery of the bodies. Despite this the generals in charge were charged and executed when they returned.

Diocles and others who had overseen the defeat were now under high scrutiny and in 408 BC Diocles was exiled as a result, and from this point we don’t hear much about him save that anecdote about his death I mentioned earlier. If this was true then presumably he was recalled though a politician with strong democratic leanings being recalled at a later dates seems unlikely for reasons which will become obvious.

Hermocrates had settled the score against his political rival as it’s difficult to consider what he had just done with the remains unless it was to undermine and sow discontent with Diocles. With that said he was still an exile and perhaps the plan had been to have his enemies forced out of Syracuse and his exile to be annulled. But that second part didn’t happen. It’s also possible, especially given what happened next that Hermocrates had little intention to return to the political system which had seen him exiled. It seems more likely that he wanted to sidestep it.

Hermocrates co-ordinated what seems to have been a power grab and specifically a very tyrant shaped power grab. Communicating with his supporters in Syracuse he arranged to arrive outside a city gate at night with a small number of soldiers. Presumably he would then enter the city and before any resistance could be mustered seize power. Of course, he might also plead his case and ask to be recalled from exile in person. But that doesn’t sound very plausible.

As to his intentions, we’ll never know because word had gotten out and both Hermocrates and his supporters were ambushed by a group of Syracusans. Hermocrates was killed and his supporters met the same fate or were arrested and then themselves exiled. That is with one notable exception, and I’ll come to him shortly. So ended Hermocrates, a very interesting character who I feel deserved a better end.

For Syracuse and the other Greek cities the threat of a returning Carthaginian force needed to be mitigated. Ambassadors were sent to Carthage requesting that Carthage ceased hostilities, though perhaps request might be too strong a word. At best Syracuse could hope that Carthage might find other options elsewhere. The response from Carthage was ambiguous and served only to confirm what Syracuse must have suspected, namely that Carthage still wanted more. We might also figure in the actions of Hermocrates who had rallied a reasonably sized force, partially resettled Selinus and launched attacks on Carthaginian territories. With this in mind could Carthage ever trust that the Greeks wouldn’t just use peace to regroup and then attack them once the situation was more favourable.

The hero of Sicily, Hannibal Mago, was chosen to lead an army. This time of huge proportions. Diodorus cited two sources he used, Ephorus and Timaeus who were roughly contemporary. Ephorus had the army at an eye-watering 300k with Timaeus providing a smaller 120k. It’s a good example of how even contemporary sources might differ. The reality was that a much smaller sized army was more likely, an army half the size of Timaeus’ 120k would require huge logistical support. With that said Carthage did have a base of operations on Sicily but even so even 60k would have been a very large army.

Just as a note and a chance to make a dig at Thucydides about his whole idea that Athens was trying to conquer Sicily – a point I made in the previous episode. When Athens launched the Sicilian Expedition the military force numbered just over 5k. I know, but as I said in the previous episode it just really irks me.

In 406 BC Hannibal landed with his forces in western Sicily. Syracuse had been amassing a response and had sent out emissaries to the Greek cities on Sicily to form a unified block. Acragas, on the south coast, was the obvious target for Carthage and so they began to bring in everything from around their city inside it as to deprive Carthage of any resources. According to Diodorus the city was fabulously wealthy. Its citizens lived well as made clear with a decree that guards who spent the night at their post were only allowed two pillows and a mattress. Tough times indeed.

The army of Hannibal soon arrived nearby and offered Acragas the option of neutrality, but these terms were not accepted. As was custom the besiegers cleared buildings and anything near to the walls so they could build a mound up to the city walls. However, in doing so the soldiers of Carthage demolished a very large building, well a tomb in fact, the Tomb of Theron. You might remember Theron from episode 2. He was a tyrant at Acragas and as the tomb was being broken down lightning struck it. Soothsayers in the Carthaginian camp had warned against damaging the tomb and though a coincidence what happened next must have vindicated them in the eyes of those Carthaginian troops who began to suffer.

Earlier I spoke of how a force besieging a city might operate and how the Carthaginians seemed to have developed a way of storming the city walls. This may have been Diodorus retrospectively applying what he understood by siege warfare of his day. But there was something which anyone in a siege in the 5th century BC and centuries later would have known about. Disease.

Large concentrations of people living in relatively unsanitary conditions, often the case with an army at siege, could easily be ravaged by disease. Think of the arrows of Apollo which blighted the Greek camp early on in the Iliad. Think of the bouts of illness suffered by the Athenian forces who laid siege to Syracuse which I mentioned in the previous episode. This great fear was visited upon the Carthaginian camp and amongst the victims was one Hannibal Mago. Diodorus recounted how the Carthaginians looked to bring favour from the gods with sacrifices which even included that of a young boy.

The new Carthaginian general was called Himilco and now he faced a different threat albeit not directly. A force from Syracuse numbering 30k arrived and immediately engaged with the Carthaginian army who were driven back. The Syracusans, under a general called Daphnaeus, didn’t pursue them and the rationale given was that Daphnaeus didn’t want to run into the main Carthaginian force. This presumably means that the force besieging Acragas was an advanced detachment of it.

But Daphnaeus wasn’t being passive. He made for the Carthaginian camp nearby and laid siege to it, cutting off any supply routes. This caused a near mutiny of the mercenaries in the camp, but Himilcar, the general at the camp, stalled this with a bribe and a promise that everything would be ok in a few days. The promise Himilcar gave wasn’t empty. It was based on the fact that he knew a number of supply ships were sailing towards Acragas and these weren’t under escort. When they were intercepted and seized by the Carthaginians the situation was reversed. Now Carthage had the supplies it needed or could at least eventually get to whilst the Greeks besieging them knew that they had lost their logistical support. The Greek force was only a temporary one and now the situation looked hopeless. Acragas had very little stored and so couldn’t resist any sort of siege, those supplies had been crucial and had they arrived presumably they could have bought the city time.

There was only one choice, as at Himera there would be another evacuation and another empty city. The people gathered up what they could carry and at night they made for Gela this time by foot.

When the Carthaginians entered Acragas it was largely a ghostown, as you might expect Diodorus has accounts of the Carthaginians acting in a barbarous manner – pulling people from their sanctuary in the temples and showing no mercy to those who had remained. A huge amount of loot was taken including the Brazen Bull which I mentioned in episode two.

Back at Syracuse an Assembly of the people was called and there were raised voices and fingers being pointed at all angles. Blame was thrown around, firstly at the generals, then the leaders at Acragas and even at Syracuse. After all it had been Syracuse who had largely called the shots and under them the Greeks had lost three substantial cities.

In amongst the name calling and shouting a man stepped forward, his name was Dionysus. He was from a middling family and was a clerk, a respectable job. Up until this point he’d been largely anonymous, though there was that incident where he’d managed to escape when Hermocrates and his supporters had been set upon. Yes, this was the individual who had slipped away, and his political instincts now charge.

Dionysus advocated that the generals be punished. Not through the standard process, let’s do it right now. This kind of firebrand rhetoric drew support and when he was threatened by the officials with a fine if he spoke anymore a wealthy citizen called Philistus stepped forward and said he’d happily pay any fines issued as long as Dionysus kept talking.

Dionysus became the man of the moment – highly popular, a real crowd stirrer and you probably know where this is heading. He pushed through a law to recall those who had been exiled as Syracuse needed all it could muster. Some of those exiles would presumably have been the fellow supporters of Hermocrates but even if not they would return and now be obliged to him. Did this include Diocles? It’s not clear and perhaps unlikely as I mentioned earlier.

In a short space of time Dionysus became the dominant politician at Syracuse and he was soon to extend his popularity elsewhere.

Gela, to the west would presumably be the next city along the southern coast to fall. Syracuse had deployed a Spartan there called Dexippus with the job of defending it. Now one of the generals, Dionysus took a force there to bolster its defences and immediately played politics once more. He got involved in a stand off between some rich nobles and the poor, finding in favour of the poor he had the nobles executed and confiscated what they owned. This he used to pay off the soldiery there and those he’d brought along. Almost overnight Gela was celebrating his name.

When he returned to Syracuse he did so with a revelation. Himilco, the Carthaginian general, had sent an envoy to him. The premise of the envoy was to discuss the captives taken by Carthage but secretly it was about him walking away. The envoy told Dionysus that Himilco had secretly bought off the other generals over to the side of Carthage. He knew that Dionysus wouldn’t join him presumably because Dionysus was just so upstanding a fellow who would never sell his city out. Instead Himilco requested that Dionysus just step aside.

Dionysus was so outraged by this obviously not fabricated in any way event that he offered to step down as general because he couldn’t work alongside these traitors. The next day an Assembly was called to discuss this, and Dionysus came armed with other charges against his fellow generals. In a moment of pure coincidence, and yes, that is sarcasm, one voice shouted out that it would be better if there was just one general with supreme power and it should absolutely be Dionysus.

If you listened to my episode on Tyrants and even if you didn’t you’ll know where this is headed. But what was missing was a bodyguard which a tyrant usually required. Copying a trick by Pisistratus, the tyrant of Athens, Dionysus feigned an attempt made on his life. It was now crucial that he have a bodyguard to keep himself safe from those who were set against him. This he duly received.

In 404 BC Syracuse therefore had its first tyrant since the removal of Thrasybulus back in the 460s. The mixture of tyranny and a Carthaginian force on the island weren’t exactly new elements, but there was something unique about it all. In particular this Carthaginian force was threatening Syracuse directly. It was rumbling towards Syracuse and Dionysus needed to act fast.

In the next episode I’ll pick up on what happened next.