I hope you have enjoyed the ancient Sicily miniseries – here is some supporting content! Don’t forget to rate and review – I forgot to mention that you can also find this podcast on Reddit.

Maps

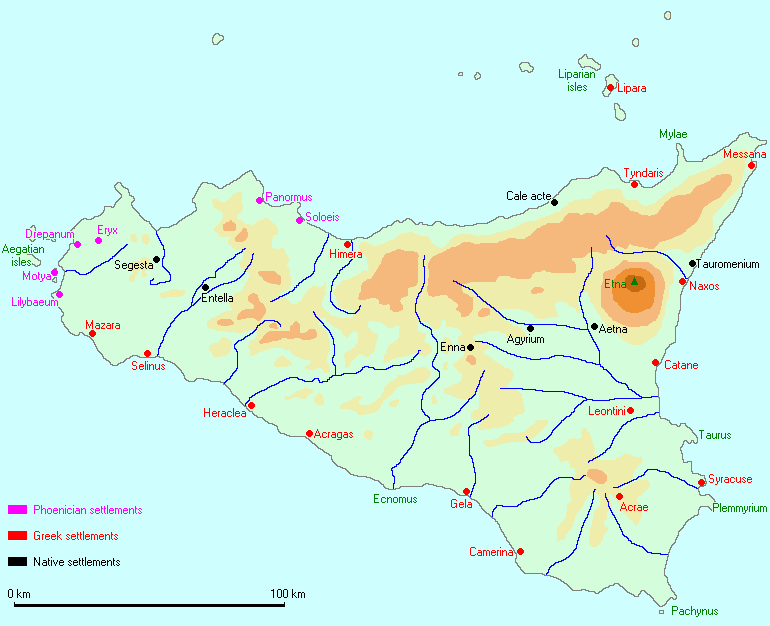

In order to orientate the below map is very good. You can see Motya off the western coast, to the north east Eryx and Syracuse on the other side of the island. Also Messana (Messene) in the top right.

A great map from World History which I’ve cropped so you can see how Locri was important in relation to Regium and the Strait of Messina.

You can see from this NASA image just how narrow the strait it. Both Rhegium (Reggio Calabria) and Messene (Messina) were gateways (those white dots in the water are ships).

The Motya Charioteer

This marble statue was found at Motya and is dated to the around the 470s BC. It’s the source of much discussion, titled the Motya charioteer it may have been a piece siezed by Carthage from a Greek city on Sicily during the campaigns in the later 5th century BC. Or it may have been carved at Motya – there was a lot of cultural transmission so perhaps a Greek at Motya carved this?

It was found in a layer associated the with the sacking of Motya in 398 BC. Was it really a charioteer, or something else?

I’ve mentioned Motya in two pieces on this blog – one concerning the possible use of a sacred pool there as a way of charting the stars. The other was about whales in the ancient Mediterranean.

Reading List.

Bonacini, E & Castornina, A. Euryalos Castle and Dionysian Walls in Syracuse.

Cross, N. Insterstate Alliance of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World.

Dudzinski, A. Diodorus’ use of Timaeus.

Haberstroh, J. Dionysius of Syracuse: A Tyrant Turned King.

Lampadiaris, N. Syracusan Imperialism.

Lewis, S. The Tyrants myth in Sicily from Aeneas to Augustus (ed Smith & Serrati).

Littman, RJ. The Plague of Syracuse.

Nigro, L. The Temple of Astarte ‘Aglaia’ at Motya and its cultural significance in the Mediterranean Realm.

Pownall, F. The making and the unmaking of the memory of Gelon of Syracuse.

Savocchia, L. The Deinomenids of Sicily.

Sanders, LJ. Diodorus Siculus & Dionysius of Syracuse.

Dionysus of Syracuse and the origins of the ruler cult in the Greek world

Transcription.

Building projects, secret deals, weddings and more Carthage. What more could you ask for – join me as I discuss the many headaches of Dionysius I in the ancient Sicily miniseries on the Ancient History Hound podcast.

Hi and welcome, my name’s Neil and in this episode I’ll be continuing my miniseries on ancient Sicily by picking up with the famous tyrant Dionysius of Syracuse and the various issues and dramas he had early on in his reign. This episode covers roughly from 406 BC and lasts a decade till 396 BC. But what a decade it was as you will hear.

If you want to find me in the stormy waters of social media you can do so on TikTok, Instagram, YouTube and now Bluesky as @ancientblogger. If you want more content including episode notes for my podcasts, including this one, why not try ancientblogger.com – you can also message me there or go old school and send an email to ancientblogger@hotmail.com

Reviews and ratings – please keep it up. These are crucial in giving this podcast more visibility. New listeners are great, but I want to also give a shout out to all those who keep coming back, there are so many podcasts and the fact that you make time for me is wonderful.

Before I begin I need to provide two corrections and an update. In the previous episode I ended it by stating that by 404 BC Syracuse had its first tyrant in place since the 460s. I meant 406 BC and that’s where the episode ended, namely with Dionysius managing to secure supreme power. The second correction is where I mispronounced his name, you may have heard me call him Dionysus, it is of course Dionysius.

As for the update – the chances are this will be the last episode for 2024 but I’ll be back in 2025. Podcasting is a hobby I really enjoy, I have been doing it for several years now after all. But it’s also demanding. I spend most weekends and at least two evenings a week either researching, scripting, recording and editing an episode. I don’t have a any in reserve, so the minute one ends the next one begins. I also have a real life to contend with and the demands it can make. So any dramas, sickness or just nice things can affect the progress of an episode. Believe it or not solo podcasters commonly suffer burnout, particularly those new to it who are terrified that if they don’t keep up with their schedule they’ll lose listeners and their stats will suffer.

I got close to this situation a few years ago – but I made peace with the fact that I’ll record and release without sacrificing quality or my work/life/podcasting balance. Anyway, I’ve been meaning to say this for a while – if you are a podcaster feeling the pressure of it all – drop me a line if you want to chat. I’ve spoken with several podcasters about this so you won’t be the first.

Right then – let’s get on with the episode.

The previous episode in the miniseries, Revenge and Ruin, ended with the Carthaginians heading towards Syracuse in a seemingly unstoppable fashion having taken cities such as Himera, Selinus and Acragas by storm. At Syracuse an ambitious clerk had risen to the position of tyrant through political cunning which included accusing his rivals of secretly aiding the Carthaginians. This individual, Dionysius, was now a tyrant of the city. However, one with a big problem – ironically Carthage and its success against the Greeks had been used by Dionysius in his rise to power. But now he faced that threat directly.

Much of our information about this part of history comes from Diodorus Siculus, a historian born on Sicily and writing later in the 1st century BC. I have mentioned him in previous episodes as he was an important source. Book 14 of his work supplies us with much of the story here and it’s argued that he relied on contemporary sources to form his narrative. These were Timaeus of Athens, Ephorus and Philistus. We cannot equate contemporary with accurate though, as you might remember from my mini rant about Thucydides from the Sicilian Expedition episode. Indeed, you’ll hear how Ephorus and Timaeus differ in this episode.

In 405 BC Carthage made its move against Gela and Diodorus wrote how the citizens led a fierce resistance to the initial Carthaginian onslaught, each day the Carthaginians attacked the walls and each night the Gelans repaired them. Soon help came in the form of Dionysius who had assembled a force which numbered 30k, according to Timaeus. This force commanded by Dionysius included navy, infantry and cavalry and each would have an important, if not complex, role to play.

Dionysius’ initial tactic was eminently sensible, hit the supply lines with navy and cavalry and wear down the Carthaginians. But that was only the first part, after 20 days of inactivity a plan came together which was as bold as it was complex. Rather than a single mass engagement the Syracusan attack would involve smaller units each attacking at different points across the enemy front line. The idea was to sow confusion, the moment a breakthrough was made the Greek force would then hit another spot. It would be a rolling attack made at different points.

It was a risky strategy because if the Syracusan units didn’t attack in unison they would be easily overpowered and that’s what happened. Had it worked we might be talking of Dionysius as a masterful general but it didn’t and so we aren’t. Unable to bring their plan to bear Dionysius was defeated and only managed to retreat through a ruse involving lighting many, many fires at night to make the Carthaginians think they were still encamped back in Gela when in fact they had marched back at night.

The following day the Carthaginians entered an empty city. Gela, along with Selinus, Acragas and Himera was now in broken pieces. As he travelled back to Syracuse Dionysius and his army stopped at Camarina where he evacuated the people there as well. This had been a location which had traditionally not always seen eye to eye with its parent city of Syracuse but here the people gathered what they could and moved out. Diodorus painted a pitiful scene in which soldiers looked on aghast as maidens of marriageable age rushed along the road in a manner described as improper for their age before commenting that the stress of the moment had done away with the dignity and respect which are shown before strangers.

Dionysius now faced mumblings amongst his men, and this led to a group of cavalry riding off to Syracuse. When they arrived, they made for Dionysius’ house, pillaging it and assaulting his wife. The tyrant hadn’t been ignorant of this rogue section of cavalry riding off and had also raced back to Syracuse, the force with him were able to eventually catch them in the marketplace, killing some with the others fleeing to nearby Aetna.

With one internal revolt crushed the larger external one still loomed large. Carthage hadn’t been stopped and now Syracuse faced an army which had made short work of Greek walls in the other cities it had taken. Perhaps the only source of hope was that some years earlier Syracuse had faced the might of Athens and been in a similarly desperate position before things got better. Back then the saviour had been overseas support and perhaps a few mistakes by Nicias, the Athenian general. However, this time no such dynamics were in play.

And yet, despite this somehow Syracuse escaped the experience of Carthaginians sacking the city. I say somehow because the section covering this in Diodorus’ account didn’t survive. When it does pick up it tells us how Himilcar, the Carthaginian general, sent a herald to conclude terms of peace with Dionysius which was agreed. The terms stripped Syracuse of much of its power base. The cities of Leontini and Messina were now independent. But most importantly Syracuse had survived.

The big question in the room was why? What had happened which had saved Syracuse? There are some ideas, a strong contender is that Hamilcar’s army was sufficiently weakened through plague to force him to step back and force severe terms. This wouldn’t be the first instance of a Carthaginian army suffering from disease whilst on campaign on Sicily. It wouldn’t even be the first instance of an opposing army suffering from this whilst near to Sicily. When Athens had laid siege to Syracuse it had been forced to camp on the marshy area near to the west. Plague or disease was a plausible reason.

Another argument suggests that Carthage was facing threats elsewhere and so redeploy its forces elsewhere. Perhaps it was a mixture of both. Dionysius might have breathed a sigh of relief, but this peace had come at a cost though it wasn’t one which Dionysius had any intention of keeping.

As the Carthaginian forces headed back across the horizon Dionysius was planning war. Perhaps the only silver lining in the Carthaginian successes on Sicily had been that they had left blueprints of their strategy amidst the broken ruins of the Greek cities they had conquered. The concept of a siege for Greeks was largely formed of two tactics. The first was good old-fashioned patience. Cities were easily encumbered with those from the nearby towns and villages escaping to them and though they might bring in a bit of extra food the situation in a city could deteriorate very quickly. As such simply encircling it and cutting off routes in and out of the city was often enough. This had been the primary tactic of the Athenians when they had laid siege to Syracuse and I covered this in the Sicilian Expedition episode.

The second tactic was a variation of the first. However, this involved appealing to a disaffected group within the city who might want to ally with those laying siege to it. Perhaps a group of nobles who weren’t happy with a lack of power or a political party of sorts. Ultimately the pay off would be that, under new ownership, they would assume a loftier position than before. Once this group had agreed they might leave a gate or two open or swing favour to accept the demands of those besieging.

But Carthage hadn’t done anything like this. They had been masters of the smash and grab, acting in horrifying expedience. They got over the walls quickly and the Greeks had little to counter this. Knowing that he’d be going to war Dionysius embarked on a series of actions to ensure that he and therefore Syracuse would be far better prepared and in the years following 404 BC these fell into three main categories. Improving the city’s defence, upgrading its offence and shoring up his position politically.

In terms of improving the city’s defence, well, eyes turned towards two locations – the plateau known as Epipolae to the north and west of the city and to Ortygia, the island upon which Syracuse was founded. For those who listened to the Sicilian Expedition episode you may remember Epipolae. This, as mentioned, was a plateau which essentially controlled the northern and western routes out of the city. Given where Syracuse was located those were the two land routes it had. When the Athenians had laid siege to Syracuse Epipolae had been the initial battleground with both forces looking to gain control of it.

When Syracuse and Athens had contested the plateau much of the action occurred on the eastern end, the part which overlooked Syracuse. However, the main way to access it was from the western end which boasted a gradual incline rather than narrow steep tracks. It was here that Dionysius built a fort known as Euryalos. This, along with walls prevented access to Epipolae from the west, exactly where a Carthaginian force would be coming from.

The building took several years, beginning in 405 BC and nearing completion in 396 BC. According to Dionysius 60,000 workers were hired and 6,000 oxen moved the stone to where it needed to be. Tyrants had traditionally been associated with big civic projects and for good reason. Firstly, these fostered a sense of civic pride.. The Greek city states were fiercely competitive with each other so we can assume this helped boost morale – something which was much needed. Syracusans might now boast about how expensive and modern their fortifications were.

There was also an economic benefit. This activity provided work for people across all levels in Syracuse. The poor as labourers, the merchants who brought in the needed resources and all those involved in what we’d now call the supply chain. Dionysius made sure he made good political capital out of it. He attended the construction personally, holding competitions to see who could build their sections first and dishing out prizes. It would be easy to dismiss this, however, it’s thought that Philistus, a minister of his was the source and it does fit with Dionysius’ approach to politics. I would also add that perhaps he used these visits to gauge his popularity and keep his political compass orientated.

The other main improvements to defence were a bit more, let’s say personal. The island of Ortygia was now fortified and homes allotted there reserved for Dionysius’ most loyal followers and some of his mercenaries. In addition, a harbour was built there. It was what any tyrant wanted, a refuge but a grand one at that.

Just as Dionysius realigned his defences to the new type of threat he realised his army and navy would need to do things differently. Around the beginning of the 4th century BC, he brought in experts from afar to not only build weapons but design new ones. Diodorus wrote that it was here that the Greeks first developed their catapult. I say their because it doesn’t seem that this was new elsewhere and exactly what the catapult was is debated. From Dionysius’ description it was a mechanical device which shot arrows, not then the type which might fire balls of stone.

It wasn’t just on land, for his navy there was the newly designed quinquereme a type of heavy warship which could carry a larger complement of marines.

I now come to the third category, improving his position politically. Dionysius looked to improve his standing both at Syracuse and outside it through marriage. But not a single marriage, rather Dionysius married two women.

If you are thinking ‘wasn’t he already married’ well, the sad truth of it is that his previous wife had died because of the assault I mentioned earlier. The move to polygamy wasn’t seen by the sources as particularly good, especially since it was something which the Persian Kings did. This was used to build a picture of Dionysius more comfortable with the eastern trappings than the Hellenic ones.

However, both marriages were politically a good idea. One wife, Aristomache, was from Syracuse and from a sound family, this most likely secured the loyalty of an important faction there. The second wife, and the way he went about it, reveals how much politics was involved. Dionysius turned his eyes to the northeast of the island and across the straits of Messina for a political alliance which would secure the eastern part of the island. The city of Messina was allotted land which bought Dionysius political goodwill. But across the straits was Rhegium, modern day Regio Calabria and relations with it were not at a good point.

In the 420s, when Athens sent its first small expedition to Sicily Rhegium had been the base of its operations. Syracuse had clashed with it as a result. Though it hadn’t fully supported Athens in the second Sicilian Expedition, the more famous, or infamous one, it had offered the Athenians harbour. In short it was no fan of Syracuse. And that wasn’t necessarily a problem except for the fact that being just over the narrow straits meant that Rhegium could prove dangerous if Dionysius was campaigning out of the city, say for example if Dionysius was leading a large number of troops to the western part of the island. An offer of marriage was sent, and the response wasn’t just a no – it was an insult. Rhegium did offer a bride, but no-one from a noble family and instead the daughter of the public executioner. This, then was what Rhegium thought of Dionysius, and it was an insult which wasn’t forgotten.

Perhaps it directly influenced Dionysius’ next move because he then made the same offer to Locri, a town to the southeast of Rhegium and a strong rival of Rhegium. The outcome here was positive, and he now had the hand of Doris, daughter of a leading noble there. This interest in southern Italy might seem an overstretch. Why bother? Well, southern Italy was important to Syracuse. Take the mercenaries which were sourced by there in large amounts by Dionysius. If you consider the geographical context the southern tip, or toe, of Itay offered an easy path to Syracuse. As such it needed to be secured. If you couldn’t secure it through an alliance with Rhegium (which sat on the Italian side of the strait of Messina) then keep Rhegium on notice by allying with its rival.

These two marriages also brought two characters into play who I’ll be picking up in future episodes. Dion, the brother of Aristomache, who became a trusted advisor of Dionysius and with Doris he had a son born in 397 BC named Dionysius.

With much of this in place Dionysus could now settle some scores. Although the defences weren’t quite finished he gambled on them not being entirely needed, at least not initially. Dionysius hadn’t built them not to be tested but any counter from Carthage would take time and he hoped that they would be finished by the time they were needed. In 398 BC he launched his attack and did so against the Carthaginian city of Motya.

For those who have listened to the earlier episodes you might recall this being the first colony on Sicily and a Phoenician one at that. It was located at the far western tip of the island, itself on a small island in a lagoon. In the mid-6th century Carthage, itself another Phoenician colony, had attacked and taken it as their own. It was a vital location, both strategically and commercially. Perhaps more important to Dionysius was its importance symbolically, to make a real stand against Carthage was to make war on its main centre on Sicily.

Dionysus advocated for war in the Syracusan Assembly, possibly to ensure he had the backing to do so and made his appeal on three broad points. The first was that Carthage hated the Greeks, that Carthage lacked manpower and resources due to a plague back home and finally that those Greek cities under the Carthaginian yoke needed to be liberated.

Each of these points are worth assessing. Did Carthage really hate the Greeks? In one sense the damage they had wrought on the Greek cities they had effectively razed in recent years would have supported this, or at least courted an emotional response from those in the Assembly. However, you could also counter that Carthage hadn’t been the aggressor when it had gotten involved with the Greeks on Sicily. I covered this is the previous episode in case you want more details on how and why war with Carthage had ensued in the years previous. There was also a long history of Carthage and the Greek cities being largely content with each other.

As for opportunism, well, it may well have been that Carthage was still having issues with the plague back home. But as you will hear they weren’t exactly impotent. As for the final point, this was an appeal to Syracusan pride. Let’s free the Greeks whether they want to be freed or are even in a position to be freed. A more cynical read would be, let’s get our dominance on the island back and get those Greek cities back in their place.

So it went that in 398 BC Dionysius took his men westwards. Diodorus wrote that this force consisted of 80,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry with 200 warships sailing road the coast. That’s a very large force and we might consider a smaller number to be more realistic. This force, or at least the infantry and cavalry, headed to Eryx, modern day. Eryx was a native settlement and seems to have incorporated Phoenician culture as well as Greek, though naturally when Dionysius arrived they were keen to point out that they were no friends to the Carthaginians.

Dionysius split his forces and whilst one campaigned in the area against the few settlements allied with Carthage the others were set to work building moles or earthworks across that lagoon. Whilst Carthage had no substantial force on the island it did retaliate with a fleet which attempted to trap the Syracusan navy which was largely stationed now in the lagoon in which Motya sat. This was unsuccessful and eventually the infantry was able to build an earthwork across the water and at this point it was largely a matter of time. The new artillery kept defenders off the walls with towers and rams working to secure a section of Motya’s walls. Eventually a breach was made and Syracuse moved in to take the city.

Often the most dangerous part of the siege for the attacker was if they managed to get in. In a weird reversal they would now be under siege, well sort of. Unfamiliar streets with barricades and all the while hit and run attacks from those who knew the layout of the city a lot better. From above defenders, which might include women and children, would be throwing objects from rooftops.

However, at best this delayed the inevitable. Diodorus described a savage sacking of Motya by the Greeks. Albeit one which was more civilised than when Carthage had sacked Greek cities. In those instances, temples were not respected and those seeking sanctuary within were dragged from them or butchered where they stood. Dionysius, being a civilised Greek, appealed to Motyans to head for the temples where their safety would be guaranteed. Just in case for a moment you thought that this was a humane side of Dionysius, well it wasn’t it was because he needed to ensure that the bills could be paid. The dead don’t sell well, whereas all those who survived could be sold as slaves to refill his treasury.

Following the sack Dionysius rested his men and continued to campaign in the west of Sicily. Across the sea Carthage assembled a military response and Diodorus cited the numbers which Ephorus and Timaeus, those more contemporary sources, had recorded. Ephorus had 300k infantry, 4k cavalry and 400 warships. Timaeus gave a much smaller size, just, and I do the airquotes thing here, just 100k in total with 30,000 of this raised in Sicily. I’ll leave you to ponder on those numbers.

This force, under Himilcon, retook Motya and headed to a place you may not have immediately thought of – Messene. You may remember this city from previous episodes, it was on the northeastern tip of Sicily and on the Sicilian side of the Strait of Messene which separates Italy and Sicily. So why here? Well, it firstly provided great harbour facilities and was close to Syracuse. It also ensured that no reinforcements could come across the strait. Though Messene tried to put up a defence it was to no avail, their defence not helped by crumbling walls and large gaps in others. It must have been a nice day off for the siege engineers.

The issue facing Dionysius as he headed back was what to do. The local tribes near Syracuse had rebelled. This wasn’t that surprising; Dionysius had attacked these peoples after the first truce made with the Carthaginians. The reason back then had been their alliance with Carthage – why had they allied with Carthage you might ask? Well, because of how they’d been treated. You might detect a pattern there. It turns out that treating locals really badly doesn’t really get you anywhere particularly when they rebel which you resolve by treating them badly.

The initial clash between Syracuse and Carthage wasn’t a land one. Though Himilcon had moved south along the coast his route was blocked by an erupting Mount Etna. This meant he had to take a longer route into the island’s interior. Dionysius took the initiative and sent his navy against the Carthaginian navy with his forces watching from the shores of nearby Catana which would improve morale. As a good idea as this was the cheering Syracusan crowds soon fell silent as their navy was beaten. Dionysius was now in a quandary. If he took his army north he’d leave Syracuse open to a navy which could simply sail into the Great Harbour there. It seemed as if the recent besiegers would themselves become the besieged.

Worse still for Dionysius was internal dissent. At an assembly meeting a man stepped forward called Theodorus and he delivered a withering critique of Dionysius. Perhaps the most personal attacks came in the form of comparisons with Gelon, an earlier tyrant of the city who was seen as a beneficial ruler. Under Gelon Syracuse had united the Greek cities on the island and given them freedom with the reverse under Dionysius.

The speech finished with an offer for Dionysius to be allowed to leave with his possessions or stay and face those who wanted their freedom. Theodorus is something of a curious figure. Did he exist or was he an invention – a narrative device to facilitate later criticisms, or even contemporary ones? We know that Timaeus, a contemporary source I have mentioned was no fan of Dionysius. Yet it’s argued that were it an invention of Timaeus the criticism might have been a bit more accurate. And that’s because alongside the valid criticism Theodorus makes are some which aren’t very good. For example, Theodorus noted how Dionysius had enslaved Syracuse. Well, the Assembly still seemed to have a function and there was Theodorus able to speak out against him. Not exactly enslavement. There was also an argument about how Carthage ruling Syracuse wasn’t much different to Dionysius ruling it.

Hmm, given how Carthage had treated Greek cities and given what Syracuse had just done to Motya I think we can agree that was highly unlikely. If Carthage were to take Syracuse it wouldn’t be very nice for anyone.

The next speaker in the Assembly was Pharacidas, a Spartan who had served as admiral for Syracuse. He was a friend of Dionysius and stated that he, and by default, Sparta, wouldn’t support a regime change. And with that the threat was over though apparently a segment of the Assembly went away cursing the Spartans. What then of Theodorus’ implied threat – namely that if Dionysius didn’t leave voluntarily there would be consequences? Perhaps Theodorus was just bluffing.

Though the internal situation had been quietened there was still the problem of the Carthaginian force once more bearing down on the city. As a display of might the Carthaginian navy had earlier sailed into the Great Harbour of Syracuse to intimidate those watching on. There were also raids made on the outskirts of the city by the Carthaginians. One such raid was on a temple to Demeter and Persephone. Impiety and the disrespect of sacred spaces was a common motif Diodorus used to underline the barbarous nature of the Carthaginians. It was also used to link to a previous consequence. You might remember in an earlier episode what happened when Carthage ignored its own soothsayers and destroyed a tomb outside Acragas. Even if you haven’t you might guess and though Diodorus doesn’t explicitly link the raid on the temple with what happened next you get the feeling he’s leaving a hint. The consequence, as you may have guessed what happened next was plague.

Perhaps a reason for not directly linking the plague to the temple raid was because Diodorus offered some rationale for its outbreak. A large body of men mixing together and a camp being located on swampy land providing very good conditions for an outbreak of sickness and plague. In particular the location as that where the Athenian force had suffered widespread sickness when they had attempted to besiege Syracuse several years earlier.

The description provided by Diodorus in many ways echoed the description Thucydides gave of the plague which hit Athens. Social disorder where the dead went unburied and as for symptoms, well, these have been scrutinized to understand what the disease might have been. The most likely candidate is thought to be is smallpox, with typhus also possibly present. Smallpox is highly contagious, and the most common form has a mortality rate of 30%.

Seizing the initiative Dionysius launched a series of attacks on the severely weakened Carthaginians. In one instance placing a number of mercenaries who he thought were likely to revolt in the front lines and then having the cavalry abandon them to be slaughtered.

Syracuse had its foot firmly on the neck of the Carthaginian army. A few battles against sick and panicked men and the entire army might be gone. And yet this, according to Diodorus, presented a problem for Dionysius. The threat of Carthage was useful to him, an enemy he could unite Syracuse against when eyes were turning towards him. When Carthage contacted him about a peace treaty he reasoned that the people would never agree to it and so made his own private deal. For the sum of 300 talents a core group of the army were allowed to escape on ships by night leaving much of the army behind.

The remaining forces, whittled down significantly by the plague, were made captives. Some escaped with others, such as Iberian mercenaries enrolled in the army. The baggage was left for the army to fight over.

In 396 BC a sort of peace had broken out, but not one formally recognised. If we take Diodorus’ account of the private deal Dionysius had made then presumably the average Syracusan thought this was a failed assault by Carthage. A break in play of sorts with the war still on but just Carthage gone. Indeed, it’s worth considering that whole account of the private deal. Did it really happen or was it Diodorus attempting to repaint a scenario to place Dionysius in a bad light. It’s not as if any of the elements of the event couldn’t be explained without Dionysius’ treachery.

Imagine that Carthage had once more been planning to assault Syracuse or put pressure on it through a show of force outside its walls. But once more disease and sickness severely affected those plans and following some successful counter attacks Himilcon reasoned that his army faced a greater risk by staying there. They had, after all, achieved some objectives. Carthage had been able to retake Motya with little fuss and it had demonstrated its abilities through taking Messene. With all this in mind the sensible decision was to return to Carthage. None of this required a secret deal. It’s also notable that the secret deal allowed Diodorus to depict the Carthaginians in a bad light once more. Their commanders were happy to betray their army and Dionysius reported how this betrayal caused rebellion in Libya which Carthage held sway over.

Perhaps, just perhaps, the rebellions had begun earlier and had been a contributing factor in Himilcon returning home. The rebellions in Libya were therefore not a result of Carthaginian cowardice, they were a reason, another reason, they might need to return home.

This is all speculation, but it’s a good experiment as to how events can be manipulated and reported in a way to set a very different narrative. Perhaps there was a secret deal, but perhaps not.

With the Carthaginians gone Messene returned once more to the Greeks and Diodorus tells us that those who lived in the Greek cities enslaved by Carthage were now free. But he says no more about this.

In the next episode I’ll pick up with what happened next and, unsurprisingly it does involve Carthage but there are new developments too. We hear of Dionysius’ literary side – for any of you Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy fans, think Volgons. There’s also the chance to avenge a person snub I mentioned in this episode.

Until then, keep safe and stay well.