The ancient Siciliy miniseries has been great fun and I hope you have enjoyed it – I will pick it up again sometime but this episode seemed a good place to pause things. You can find episode notes for the previous episode here – and why not check out the subreddit for this pocast? I also mentioned cheating at the Olympics, here’s a recent article on exactly that.

Maps & images.

It’s fair to say that this episode involved a lot of overseas areas.

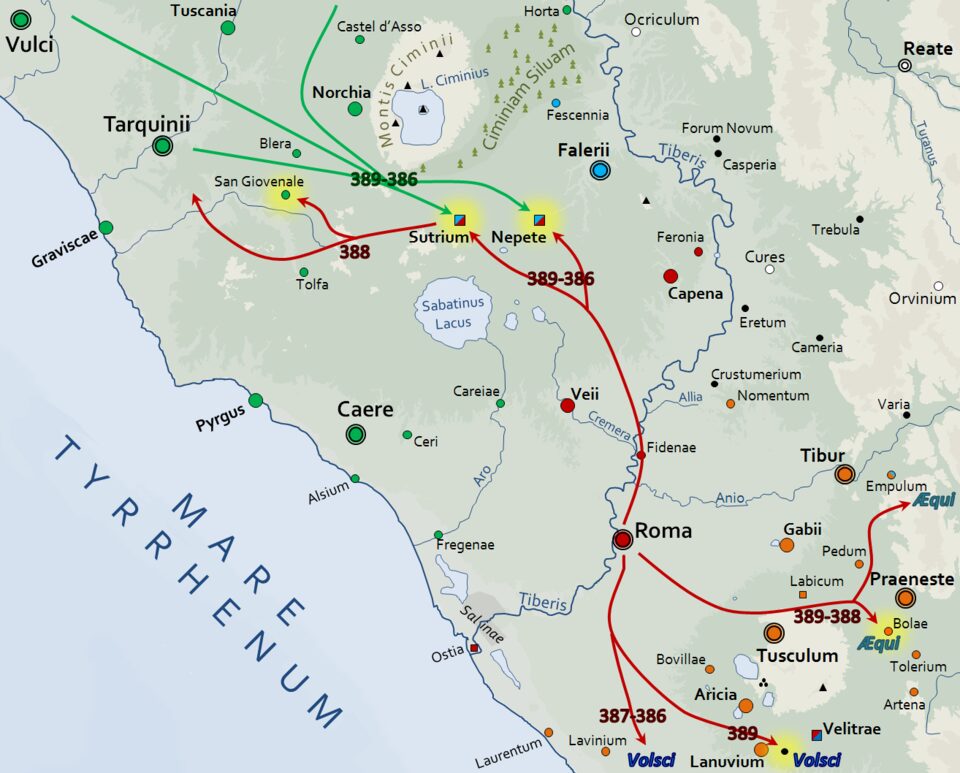

The below map gives a good overview of where some of the locations mentioned were in relation to each other.

This map gives both Caere, Pyrgi and Rome and also some of the conflicts which were going on in the 380s BC. Sardinia is the west (actually southwest) as such by reaching here perhaps Dionysius was making it known that the Carthaginian colonies there weren’t as safe as they seemed.

Sardiana lies around 120 km from the Italian peninsula. The below map shows the state of play in the mid 3rd century BC so long after Dionysius but the distances remained the same. One suggestion for Carthage having taken Motya in the mid 6th century BC was that this helped secure Sardinia.

In the episode I mentioned the helmet dedicated by Hieron at Olympia to celebrate the victory in 474 BC at Cumae against the Etruscans. Here’s the helmet with the inscription.

Reading List.

Cross, N. Insterstate Alliance of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World.

Dudzinski, A. Diodorus’ use of Timaeus.

Duncan, A. A Theseus outside Athens: Dionysius I of Syracuse and tragic self-presentation.

Haberstroh, J. Dionysius of Syracuse: A Tyrant Turned King.

Lampadiaris, N. Syracusan Imperialism.

Lewis, S. The Tyrants myth in Sicily from Aeneas to Augustus (ed Smith & Serrati).

Miles, S. Strattis, Tragedy, and Comedy.

Papachrysostomou, A. Ephippus Introduction, Translation, Commentary

Savocchia, L. The Deinomenids of Sicily.

Sanders, LJ. Diodorus Siculus & Dionysius of Syracuse.

Thatcher, MR. Identity and Politics in Greek Sicily and Southern Italy

Transcript.

Bad poetry, a curious use of red-hot nut walnut shells and overseas politics. Join me for the 7th episode in the ancient Sicily miniseries on the Ancient History Hound podcast.

Hi and welcome, my name’s Neil and in this tyrant-packed episode I’ll be continuing the ancient Sicily Miniseries with Dionysius of Syracuse. Before I get stuck into it all I need to make 3 quick points.

Up first is a big thank you for all the nice messages and feedback following my recent update. Your patience is really appreciated as are any reviews and ratings you can give this podcast. On Spotify you can even leave comments for individual episodes and it’s really good to hear what you think. It also helps this podcast get more coverage and exposure.

The second point is about where you can find me. I’m on X, Bluesky, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube as ancient blogger. My AncientBlogger YouTube channel has this podcast as audio but also videos, many from my TikTok account. There’s my ancientblogger.com website and a growing subreddit on Reddit called Ancient History Hound. I put all sorts of content on there and we’ve recently hit 2,000 followers so thanks if you are one of them listening now.

The third and final point relates specifically to the Ancient Sicily Miniseries. After this episode, which finished with the very dramatic fate of Dionysius I’m going to hit pause on the miniseries for the meantime so I can bring you other content. There are many topics I want to cover including a minisode covering popular questions – keep your ears peeled for these. I’ll probably pick this miniseries back up but given that this episode ends with the end of Dionysius it seemed a natural place to pause it all.

Ok I said I’d be quick so, let’s begin.

It’s 396 BC, Dionysius I or just Dionysius as I will be calling him, had managed to once again fend off a Carthaginian force when it was at the walls of Syracuse. Diodorus Siculus, a historian from Sicily who wrote in the 1st century BC and a main source, wrote that a great plague had hit the Carthaginians, and this had so weakened them that they cut a private deal with Dionysius which allowed the elite officers to escape whilst dooming much of their army as it lay wasting away outside Syracuse. The reason for the secrecy and privacy of the deal was because Dionysius expected that if it was brought formally to the Syracusan Assembly they’d reject it as Syracuse now had the advantage. It’s also mentioned that Dionysius didn’t want the Carthaginians wiped out entirely as they provided him with a needed enemy which he could unite the people against and of course there was that huge bribe.

In the last episode I briefly mulled this over and I want to elaborate on this further. In short, was this really the case? Did Dionysius act this way as reported by Diodorus or was it a way of painting both Dionysius and the Carthaginians in a very bad light?

What I am about to say is speculation, but I think it’s valid. It’s entirely plausible that Carthage, after fulfilling the by-then standard policy of flexing its muscles withdrew its forces. Just remember that it had retaken Motya, or what was left of it. It had more importantly taken Messina in the northeast of the island. It had then beaten Dionysius once again in battle.

At this point it could be that Carthage negotiated some form of a temporary peace or just left due to two factors which Diodorus mentions. The first was sickness in camp, a recurring motif which is entirely reasonable. The second that there had been uprisings and issues for Carthage elsewhere in the areas which it controlled. As such the best use of this army may have been away from Syracuse, rather than having to spend time and resources there.

The rationale which Diodorus affords to Dionysius doesn’t quite add up. I would imagine that Dionysius was highly motivated to get something in the win column against Carthage given his poor track record. As for him needing a useful enemy which he could unite the people against. Well, that’s possible. However, one thing Carthage had demonstrated, time and time again, was that it could assemble large armies quite easily. It wasn’t as if by defeating this particular one that the Carthaginian threat would be finally extinguished thus removing that apparently useful enemy.

Further to this point what was the reason for allowing the small group of officers to escape exactly? How would this ensure that Carthage remained a viable threat exactly? The reality was that those escaping would face criticism and probably worse back home. Their escape had no real effect in this context of preserving the Carthaginian threat.

Why then might Diodorus have described the events this way? It made Dionysius look very bad and in different ways. There was his personal greed for bribes, the fact that he was in a weird collusion with Carthage and that he wasn’t putting the city first. As mentioned Carthage also came out badly, after all their commanders and officers were happy to give a bribe so they could escape and leave their army to death or enslavement. As stated I am speculating here, and it may have been exactly how Diodorus described but given his anti-Dionysius and anti-Carthage leanings you can see why it feels that he might have, shall we say, revised things.

I should add something about Motya as I mentioned it moments ago. This had been the most important Carthaginian city on the island, although technically it wasn’t really on the island. If you remember episode 1 it had been founded on an island in a lagoon off the western tip of Sicily. After its capture and razing the Carthaginians founded a new city called Lilybaeum to the south on the tip of western Sicily. This was able to facilitate trade and grew to be a highly important Carthaginian city.

Though the Carthaginian army was gone there was that city they had taken, Messina. This stood on the Sicilian side of the strait of Messina a narrow body of water which separates Sicily from the toe of Italy. Messina was retaken and resettled with mercenaries and those from Locri, a Greek colony in southern Italy. Locri, as you might remember, was where one of Dionysius’ wives hailed from and this was a Greek colony which you will hear more of shortly.

Across the strait of Messina, on the Italian side, was the Greek colony of Rhegium. This was a location which Dionysius had no warmth for. You might remember in the previous episode that Dionysius, conscious that Messina and Rhegium were very important strategically, had a few years ago made conciliatory moves towards Rhegium through an offer of marriage.

Rhegium’s response wasn’t just a no it was a no with an insult attached. They wouldn’t let a noble marry Dionysius, instead the executioner’s daughter was offered in place of one. The implication wasn’t subtle. Dionysius wasn’t a real noble and he had no value in their society.

The response from Dionysius, again as I mentioned in the previous episode, was to form an alliance through marriage with Locri, which was a long-term rival of Rhegium. The aim of this was to have an alliance in southern Italy which he could then use to check Rhegium.

You might be wondering what this issue with Rhegium was, well it wasn’t exactly a new thing. Prior to Dionysius it had been the closest thing to an ally which Athens had when it sent that expedition to Sicily and against Syracuse. In the more recent years exiles from Syracuse had amassed there. We shouldn’t think of Rhegium as a passive actor here, it had supplied ships aiding a rebellion against Dionysius early in his reign. It seems that the two were destined for bloodshed and perhaps that offer of marriage was made knowing that it would be rejected but it gave Dionysius the political capital through insult he needed to justify or build a case for action against it.

Sensing that Dionysius was fortifying Messina in order to launch an attack it a force was assembled by Rhegium with Heloris, a Syracusan exile, as its general. Heloris led a failed attack on Messina which Dionysius was about to respond to when he was interrupted by a rebellion. The location of this was the indigenous city of Tauromenium (modern day Taormina) and this was something which Dionysius was continually contending with. The native or indigenous peoples of eastern Sicily were often at loggerheads with Dionysius, and some had supported Carthage in its actions against Syracuse. The reason was that Dionysius had little time for them and had led campaigns against the peoples there to keep them in check.

Dionysius’ attempts to capture Tauromenium failed, and this generated some unwanted consequences. Perhaps sensing a weakness, the pro-Syracusan and therefore pro-Dionysius factions in Messina and Acragas were forced out of the respective cities. Messina was now independent.

Worse was to come in a decidedly Carthaginian shaped entity. An army under Mago, drawn from Libya, Sardinia and southern Italy landed on Sicily and camped near modern day Agyrium, ironically the birthplace of the later Diodorus Siculus. However, no battle was formed, and in 393 BC Dionysius was able to formally agree a truce which gave him Tauromenium and ended the conflict with Carthage.

Carthage was no longer an issue and so Dionysius could enjoy the fruits of peace, or he could focus all his efforts against Rhegium. No prizes for guessing which. But Rhegium wasn’t just new territory in terms of geography, this was, after all, his first foray into southern Italy. He was also breaking new ground politically. This was because Rhegium was part of the network of Greek cities in southern Italy and much like those on Sicily they had what you might think of as their own political ecosystem. Much like the Greek cities on Sicily they also fell out with each other and competed with one another. It was quite a complex affair, and I did an episode on Magna Graecia which included much of this.

Within this ecosystem was the Italiote League, an alliance between some, but not all, of the Greek cities. We have little information about this league. Diodorus suggests that it was formed as a direct response to Dionysius and what he thought were Dionysius’ grand plans for conquest in southern Italy. This itself can be argued against and I’ll get to that shortly. Going back to the formation of the Italiote league, well, there is evidence that it was formed in the late 5th century BC, long before Dionysius. To be balanced I should add that it’s possible this was an earlier version of the League and that it was reshaped when Dionysius started to make moves against Rhegium. Again, as I mentioned, it’s quite a complex affair given that we don’t have much information.

What is certain is that the Italiote League and Dionysius clashed in 389 BC in the battle of Elleporus. This manifested because Dionysius was laying siege to Caulonia, a rival of Locri and the League came to its defence. It was badly beaten and Caulonia was taken, razed and its territory given to Locri.

It was the events after the battle which raised an eyebrow, and which can be sieved for Dionysius’ wider policy here. The captives from the army of the Italiote League were freed. Note that they were not executed or sold as slaves but given clemency. This doesn’t seem the action of a tyrant looking to subjugate all of southern Italy. Instead, it looks rather like someone showing a diplomatic hand to keep the Italiote League on his side.

This victory had accomplished two things, it had supported Locri and shown that it was an ally, and it had isolated Rhegium from the protection of the Italiote League. Indeed, the big loser here was Rhegium, and it looked to make a deal which was accepted and involved the city paying Dionysius 300 talents, giving him hostages and its warships. Perhaps the citizens of Rhegium thought that this was the end of it, but they were to be proved horribly wrong.

Around 387 BC with the peace treaty with Rhegium still in its infancy Dionysius assembled an army and led it to the strait of Messina. He sent a message to Rhegium – would they be able to supply his army? Rhegium agreed to do so and by doing this they quickened their demise. This, as you have probably worked out, was a trap. Had Rhegium refused it would have given Dionysius an open reason to go to war with them. By agreeing though the city had reduced the supplies it would need in the event of a siege which was about to happen. There might be one way to stall the siege though, a decent navy could make things very difficult for Dionysius. But those ships were part of the earlier peace deal.

The siege of Rhegium lasted 11 months. Eventually it surrendered and Dionysius entered the city and publicly drowned the son of its leader. When the leader, a man named Phyton, didn’t break at the sight of his son’s execution Dionysius began to worry that people might start to admire him, so he was drowned as well.

By 386 BC Dionysius had achieved much of his military aims though these weren’t the only ambitions he had. This period was also witness to a number of key events in what was a real passion of his, poetry. Like tyrants before him Dionysius had curated a court where he promoted the arts. As a general observation Greek tyrants liked to foster the sense that they were cultured individuals, perhaps to divert eyes from how they’d home to rule in the first place and some of their activites.

Dionysius seems genuine in his love of the literary arts and though we have departed from tales of war for the moment there was still conflict to be found. Take Philoxenus of Cythera a famous poet and musician. For a while he was at court, the date argued is around 389 BC, and according to an anecdote he was at dinner with Dionysius when the tyrant gave a recital of his poems.

Philoxenus was asked for his opinion, and he was brutally honest, so much so that his feedback was met with arrest and time spent in the quarries. But this was a famous musician of his age, and his friends petitioned Dionysius to spare him. The appeals were successful and so Philoxenus once again found himself back at court and back once again at a dinner with Dionysius. This time some different compositions were read out – a second chance for Philoxenus as it were to give some positive feedback.

But Philoxenus said nothing, he simply got up, walked to one of the servants and asked to be taken back to the quarry. Though this is an anecdote we know that there must have been some issue between the two as Philoxenus penned a poem which was called the Cyclops. The setting was a cave where Polyphemus, the famous cyclops of myth dwelled and apparently written during Philoxenus’ time in the quarries. Not much is known about it save that the plot involved a love interest of Polyphemus but also him being outwitted by Odysseus. It was said that the character of the cyclops was based on Dionysius with Philoxenus as Odysseus. The existence of the love interest has also been suggested as pointing to some romantic conflict the two had. Possibly Philoxenus dallying with someone he shouldn’t.

Dionysius’ court also saw a falling out with a much more famous figure around this time. The philosopher Plato was invited by Dion, Dionysius’ brother-in-law to help tutor the younger Dionysius. This ended with Plato being arrested and sold as a slave on the island of Aegina. Fortunately, his friends bought him and therefore and freed him.

Whether his poetry was that bad Dionysius can be at least credited with not giving up, though perhaps he should have done. In 388 BC he dispatched a chariot team to the Olympic games, nothing unusual in that, but accompanying them were a troupe to recite his poetry.

The Olympic games much like the other Pan Hellenic games were more than just a gathering to watch events. I say events as at other games involved music, poetry and even painting. These games offered a rare scenario where people from all the Greek world and those city states could meet, and this facilitated various levels of politics. Treaties were formally renewed, discussions informally had. There was more going on off the track than on it.

True, an athlete at the Olympic games brought fame to his city and this meant that cheating wasn’t unknown. One manifestation of this was to have an athlete who looked like they might win declare that they were in fact from a different city. Pausanias recounted that Dionysius tried to bribe the father of a boxer in the boys’ competition to say he was Syracusan, but this didn’t work, the bribe wasn’t accepted.

Away from the events a Greek city could make a statement without breaking sweat. A city state might build an impressive treasury or dedicate an expensive statue. There was often a message there and it was rarely that subtle.

Take a golden shield in the temple of Zeus dedicated by the Spartans. The inscription noted that this was dedicated by the Spartans after they received it as a gift from the Argives and Athenians at Tanagra. Nice, you might think, presumably this was something given to them that the Argives and Athenians picked up for them when they went shopping at Tanagra.

Ok, I’m being facetious there but the word ‘gift’ here is not entirely correct. Tanagra was the location of a battle where Sparta had defeated both the Athenians and Argives, and the shield was presumably funded by that victory.

The Sicilian tyrants hadn’t missed this trick – a famous dedication at Olympia was a helmet taken at the battle of Cumae in 474 BC against the Estruscans. Hieron, the tyrant had supplied this with an inscription that read ‘Hieron, son of Deinomenes, and the Syracusans, [dedicated] to Zeus Etruscan [spoils] from Cumae’.

The games at Olympia were ripe for all species of propaganda and so the poetry wasn’t just a personal passion, it was an attempt for Dionysius to showcase that he was less a tyrant and more a cultured individual. At the Olympics he had Greeks from all over who could listen to his works and would then report back to their city state about how impressive he was. Dionysius might be known as less than a tyrant and more a leader who was cultured.

What, then, could go wrong? Well, as it turned out pretty much everything. Both the chariots and his poetry crashed, literally and figuratively. His poetry was mocked and his reputation as a poet left in the dust. What made things worse was that there had been a performance which caught the ear at the Olympics. It was an oration made by Lysias, a famous Athenian which had named him a despot and called upon his removal.

Losing a chariot race wasn’t necessarily all that bad – it was a famously dangerous sport. You might be involved in a crash but it not be your fault. But the poetry failing couldn’t be anything other than the fault of Dionysius. Diodorus described his response– and I quote:

“Dionysius, on learning of the slight that was cast upon his poems, fell into a fit of melancholy.7 His condition grew constantly worse and a madness seized his mind, so that he kept saying that he was the victim of jealousy and suspected all his friends of plotting against him. At last his frenzy and madness went so far that he slew many of his friends on false charges, and he drove not a few into exile, among whom were Philistus and his own brother Leptines, men of outstanding courage who had rendered him many important services in his wars”

Diodorus paints a picture of a dramatic tantrum which led to paranoia and bad decisions. But was this really the case or is it another example of finding the worst possible light to cast Dionysius in?

Again, allow me to indulge in some speculation but perhaps there had been a plot uncovered following the debacle at the Olympics. Dionysius, after all, had his reputation trashed and Lysias was there calling for him to go. The brother of a tyrant and a close advisor wouldn’t exactly be the most unexpected candidates in a plot. Perhaps they weren’t involved directly but Dionysius felt they needed to be moved out of Syracuse for a while just in case.

If so then what Diodorus is doing is reporting Dionysius’ response to what was a serious threat as simply a dramatic tantrum caused the by rejection of his poetry.

In 385 BC Dionysius undertook an overseas expedition against the Etruscans. According to Diodorus he was short of funds and raided the port town of Pyrgi. This was located some 50 km northwest of Rome and linked to the Etruscan city of Caere by a 16km long road. Pyrgi boasted a substantial sanctuary which housed temples, and this invariably stored valuable items. One in particular, the temple to Ilithyia, a Greek goddess associated with childbirth, was sacked and 1,000 talents taken.

Diodorus reasoned that this raid was solely to keep the coffers topped up. True it did supply Dionysius with funds, however, there may be other motivations there. The Etruscans had long been a commercial rival for Syracuse, you may remember the battle of Cumae in 474 I mentioned earlier. An important trade route ran down the western coast of Italy and through the Strait of Messina as such though the Etruscans weren’t exactly neighbours their effect on this trade route could be felt by Syracuse. Perhaps there had been issues and this was a show of strength.

There had also been something else going on nearby to where Dionysius raided which involved the Etruscans, Gauls and a certain city called Rome. The details, and indeed the dates, are debated but it seems that an invading force of Gauls had been in Etruria causing mayhem and once infamous outcome was that they eventually sacked Rome in, or around 387 BC. Rome had both enemies and allies amongst the Etruscans. Caere, the city linked to Pyrgi had been an ally.

The instability in the region following these events may have given Dionysius a window of opportunity. He could make a show of force against the Etruscans and fill his treasury with little, or less risk. Were this the case, and apologies for even more speculation, it’s likely that Diodorus might prefer to present it all as purely motivated by money and greed whilst also drawing a negative comparison as it had been Carthaginians who were guilty of desecrating temples for loot.

And on the subject of Carthage, well, across the sea was Sardinia. This had been a place where Carthage had colonies and Diodorus noted that the intention of the raid was to cover the cost of making war against them once more. In the short-lived invasion by Carthage, I mentioned earlier I did say Sardinia was a place where some of the forces were recruited from. It wouldn’t be implausible that Dionysius’ raid in this area was also to remind Carthage that he had a longer reach than they thought he had

In 382 BC another new war with Carthage broke out and is thought to have lasted several years, from around 382 BC to 376 BC. Despite the timescale we have little meat on the bone in terms of what Diodorus tells us. Only two engagements are mentioned, the first at Cabala was a win for Dionysius. It wasn’t just a Carthaginian defeat, they also lost Mago, their general.

The second battle was similar in many ways to the first. Known as the Battle of Cronium the location has been debated and there was a decisive outcome as well as a key figure lost in battle. However, this time it was Dionysius who was defeated. Not only was he beaten he lost his brother, Leptines, in the battle. The outcome of this was, as you have guessed, another truce with Dionysius paying 1,000 talents whilst receiving the cities of Selinus and Acragas.

In terms of Dionysius versus Carthage this was largely it though I should say that there was a brief engagement just before Dionysius died when he had tried, and failed, to take Lilybaeum. But now I’m going to look towards the east and mainland Greece. So, it’s time to give the Carthaginians a well-deserved rest.

At the start of the 4th century BC Sparta had been preeminent, by the end of the 370s things had changed massively. In 371 BC it had been defeated by Thebes at Leuctra and with this Sparta was no longer a relevant power anymore.

Syracuse had a long relationship with Sparta as you might recall. It had been a Spartan general, Gylippus, who had helped turned the siege against Athens when there had been that Athenian expedition. Another Spartan, an admiral called Pharacidas had backed Dionysius when he was challenged openly at the assembly. Dionysius seems to have monitored the gradual decline of it and trod a carefully in how he supported this once powerful ally. He didn’t want to make an obvious break from them, one which might be seen as betrayal. But when Sparta came to battle Thebes in the 370s he offered the minimal support.

One of Sparta’s long-time rivals, and opponents in this war was Athens and there seemed to be a charm offensive brewing. You might be tempted to draw a line from the failed siege Athens had made decades ago against Syracuse to the speech at the Olympics in 388 BC and from that concluded that Athens had always been an enemy. However, relations between City States were often capricious. In 394 BC there had even been a formal decree at Athens stating their friendship with Dionysius.

In 370 BC a letter from Isocrates, a prominent Athenian rhetorician, praised Dionysius as “the foremost of our race and the possessor of the greatest power”. A year later something more substantial was offered by Athens, an offer of citizenship. This was paired with a decree praising him and why I said that this was substantial was that the citizenship would have been voted for. This wasn’t a private token gesture but one which had been given a mandate of sorts by Athenian citizens who voted for Dionysius to become one of them.

Perhaps this popularity surge helped Dionysius to what must have been something he had always hoped for, literary success. In 367 BC his play, the Ransom of Hector won at the Lenaia which was a festival celebrated in January at Athens. This included a dramatic festival and though it wasn’t quite like winning at the Great Dionysia it was success, nonetheless.

This victory was to have a profound effect on Dionysius because according to Diodorus it killed him. Well, the celebrations did. Apparently these were so excessive that Dionysius drank himself to death and without reaching for a stereotype that does feel like a ‘poety’ way to go.

Summing up Dionysius is difficult, mainly because of the sources and their attitudes towards him. I’ve given some examples where I think Diodorus might be giving a less than balanced account of him. This in part through his own framing of him but also the sources he used, for example Timaeus. In truth though Dionysius suffered at the hands of many a writer and across more than one genre and century. Ephippus, a comic poet of the 4th century BC had a character in a play swear an oath which, if he broke, would force him to learn the dramas of Dionysius. Another comedy writer called Eubulus made Dionysius the main character in a play where he was mocked for his inabilities as a poet and as a despised tyrant.

Writing later on Cicero recounted how his wives would be strip searched before they could visit him privately. Another story from him details how his barber once boasted that he was the most powerful man in Syracuse because he held a razor to the tyrant’s neck. When Dionysius heard of this the barber was executed and from then on the act of shaving him was left to his daughters who had to use red-hot walnut shells to singe his beard.

Even the poet Dante got in on the act. Though it’s not entirely clear whether the reference was Dionysius or his son the Florentine poet has him ensconced in the 7th circle of Hell in his work the Inferno. Here Dionysius boils in a lake of blood as punishment for his treatment of others, perhaps it was in place of that massive hangover which he was probably going to have if he had survived.

The biggest crime Dionysius committed was by virtue of him being a tyrant. This was never much of a popular thing in antiquity, particularly from the Classical Period onwards. For the audience of Diodorus Siculus, writing in the 1st century BC the idea of an individual subverting the established political process to place themselves in power was not a popular thing. And yes, that is ironic when you think about what went on in the 1st century BC and what Rome was to become.

In spite of all that criticism of him it’s worth considering one thing that he was very good at, surviving. Dionysius came into power in his late 20s and reigned until his death in his mid-60s. He wasn’t assassinated, though there must have been plots and so we could consider him a successful ruler given these small metrics. Under him Syracuse continued an upward trend of being a very powerful city state and it’s worth thinking about his background. Dionysius had risen to power through sheer political instinct and vigour. To have survived so long he must have been an effective communicator. That is to say he must have been able to speak at all levels of society and there’s one instance of this that I think gives a very small positive window we have of him from Diodorus.

It was probably when he was using Philistus as a source, the same Philistus who Dionysius had as an advisor and who he exiled. It occurred during the building of the walls and defences very early in his reign Dionysius was said to have visited the sections being built and praised those working there, he even held competitions to see who could finish their section first. He seemed popular with the men and here I can think of him as that clever opportunist who knew how to appeal to different people. A tyrant who probably held the odd baby smiled all the while and remembered names. In short a consummate politician but also one you would not wish to cross because he was undoubtedly as ruthless as he was as good holding a grudge.

I hope you have enjoyed this episode, and I will pick up the miniseries on ancient Sicily again sometime in the future. Until then keep safe, don’t try that thing with the hot walnut shells and stay well.