The scene of a deity pursuing a mortal libinously is not exactly a rare event in antiquity. From vases to reliefs and even the backs of mirrors the love affairs of the Greek gods were an easy option for an artist to bake into life on a vase or tease out of marble. Normally the pursuing deity was male and, rather than rely on brute force, would employ some persuasive or magical tactic to satiate their desires.

Take Zeus, for example, he seduced Leda in the form of a swan, Danae as a shower of gold and perhaps most bizarrely, Eurymedousa as an ant. At least with Alcmene he took the shape of a mortal, more specifically an exact copy of her husband which just seems to be taking it one step too far. Still, at least no antennae were involved.

It’s of little surprise that the goddesses found little equality both in opportunity and the means to seduce a mortal. Lefkowitz* argues that a Goddess required consent by both parties, not for them the option of shape shifting or deceit.

Eos and mortal men.

This brings us to Eos, the goddess of the dawn and famously she of the rosy fingers who was possibly the deity hungriest for young mortal men (making Zeus look positively amateur). In her defence this was due to a curse placed on her by Aphrodite, possibly as a result of her catching Eos in bed with Ares. But Olympian politics aside the artisans of the Classical Period picked this theme up and ran with it. According to Dipla** some 190 depictions on Athenian vases featured variations of Eos pursuing her lovers and what makes this really striking is that the mortal loves of Eos only number a handful. To understand this contradiction it’s worth looking at who they were.

We’ll start with Orion, a great hunter who Eos managed to charm but was sadly slain by Artemis. Perhaps Eos had a type as Cephalus was another hunter who she ended up in bed with, the affair eventually ended. Yet Cephalus’ marriage was doomed and his wife ended up on the wrong end of a magical javelin which Cephalus threw at something he saw move in the bushes whilst on a hunt and which turned out to be, well, you have already worked it out. Tragic, but at least novel.

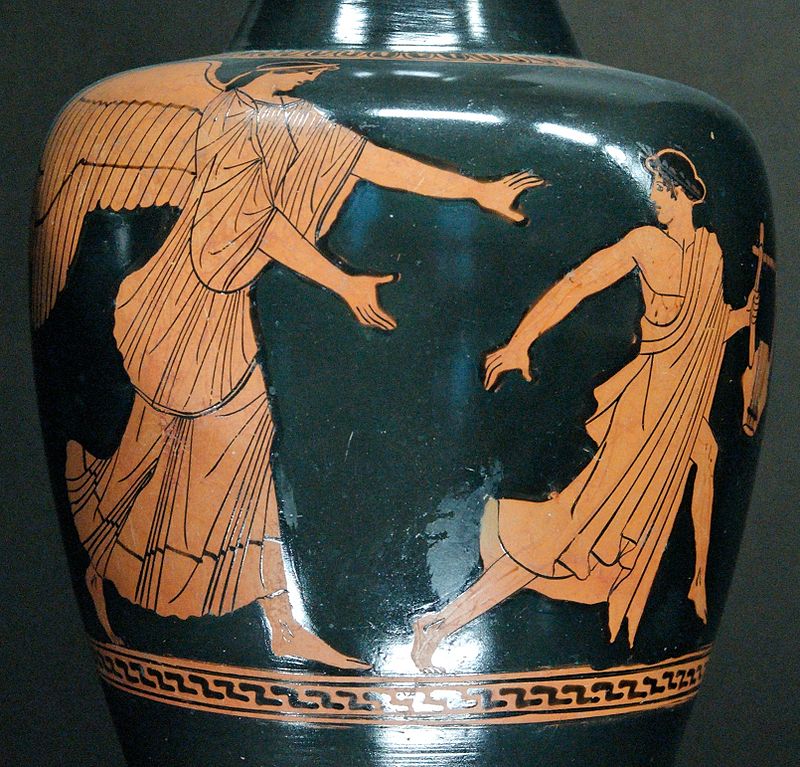

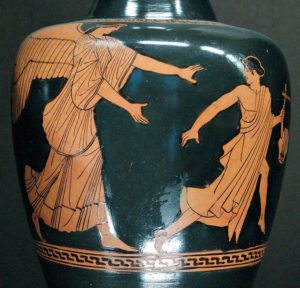

Eos pursues Tithonus, Attic red figure oinochoe, Achilles Painter, circa 470 BC

This leaves us with the other main consort, Tithonus. This Trojan prince differs from the rest by virtue of his not being a hunter, in fact often he’s depicted with a lyre and usually younger looking (which is ironic given the relationship’s outcome). Eos stole the Trojan away to Ethiopia where she bore him a son, Memnon who went on to fight the Greeks at Troy. Given the outcomes of the other relationships you’d be correct is assuming that this one wouldn’t end well.

Rather than being speared at the point of an arrow or javelin it was pedantry which supplied the ambiguous point that doomed poor Tithonus – Eos appealed for him to be made immortal and this was granted. What Eos had forgot to do was clarify her terms more accurately. Tithonus was now immortal but he would also age.

According to the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite Tithonus was left in a room to mumble to himself once he became too old, in another myth he turned into a cicada. It was a simple lesson for the Ancient Greeks – if you’re going to make a request with your seniors check the small print.

Eos chases Cephalus or Tithonus on a red figure kylix, Penthesilea Painter circa 470 BC

We’ll return to the contradiction – what made these few escapades with mortal youths such an emphatic artistic device which became so popular? Dipla noted that often the youths pursued by Eos weren’t named, and even when they were it wasn’t always clear who they were. To Dipla this meant one thing, it didn’t matter who they were, just that they were portrayed as your typical Athenian ephebe.

Eos and Athenians.

Ephebes (or epheboi) were mainly rich Athenian youths who were yet to become fully fledged citizens. They pursued a programme of study, wrestling and hunting. Two of these activities (hunting and study) formed the typical backdrops for Eos and her ambushes and perhaps this added to Eos’ appeal, that she was somehow more likely to appear.

In one fell swoop (and swoop she did) any ephebe was at risk of being the target for Eos’ attentions, it wasn’t a Trojan Prince or mythical hero who might catch the roving eye of Eos and rove she certainly did helped in no part by her wings, which she is often depicted with. Eos’ wings made sense stylistically, it could help her be identified in art, but it also underlined her ability to appear anywhere and at any time. Eos was quite capable of getting around at whim.

For an artist Eos gave the opportunity for something different and given that Cephalus was an Athenian the artists of Attica had a local boy at the heart of the story they wanted to tell. Yet Eos also offered the stark danger of passion, in the case of Tithonus getting what you want might not be so good after all.

You can also read about Aphrodite and her heartbreak (which lead to many breaks) here.

*Predatory Goddesses. Mary R Lefkowitz, Hesperia 71 (2002) 325-344

**Eos and the Youth: A case of inverted roles in rape. Anthi Dipla, Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol 9, No. 2, pp 109-133