I hope you enjoyed the episode on Magna Graecia, as promised here is some more content (including the sources I used/ further reading) and the transcription.

In case you are interested here’s the link for the museum at Pithekoussai – it’s got some great information. Perhaps one day I’ll get to visit. There is also a great piece on Pithekoussai by Penn Museum and includes some of the finds I mentioned there.

Below is the piece I referred to which warned against stealing. It’s currently in the British Museum. I also wrote a short piece on it which you can read here.

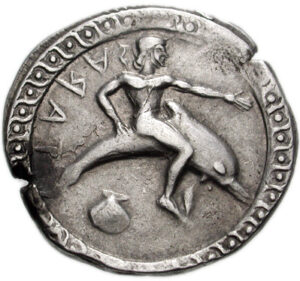

Taras had a couple of interesting foundation myths, both linked to dolphins. Pausanias (10.13.10) mentioned Phalanthus as surviving a shipwreck through the help of a dolphin and when he founded Taras the dolphin became associated with it. Yet there was also a version involving Taras, son of Poseidon, as the founder (10.10.8). The dolphin was the constant though as can be seen on this coin from Taras (circa 500 BC).

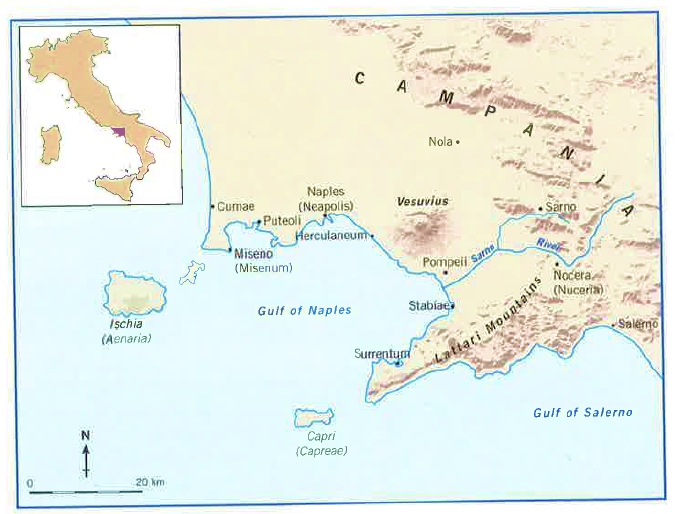

Maps.

Here’s a great map of southern Italy including the dialects spoken there.

This one gives a bit more information in regards to the non-Greek peoples (you can see the Lucanians and the Bruttians there).

As you can see – Ischia was close to Cumae.

Greeks didn’t just settle colonies in southern Italy, this map gives some idea of how far they spread out.

As I mentioned – Pyrrhus was quite the traveller, here’s his movements including the battles (and where he crossed over to southern Italy from).

Sources used / Reading list.

Athenaeus, The Deipnosophistae

Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica

Herodotus, Histories.

Livy, History of Rome

Polybius, Histories.

Thucydides, Peloponnesian War.

Beck & Funke. An introduction to federalism in Greek antiquity.

Cartledge, P. Democracy

Cowan, R. Italy

Cross, N. Interstate alliances of the fourth-century BCE Greek World: A socio-cutural perspective.

Dekk’Oro, F. Alphabets and dialects in the Euboean colonies of Sicily and Magna Graecia or what could have happened in methone.

Donellan L. Modelling the rise of the city: early urban networks in southern Italy.

Pithekoussan amphorae and the development of a Mediterranean market economy.

Changing pottery production technologies in urbanising societies in the Bay of Naples (8th -7th centuries BCE).

Fleming, D. The Streets of Thurii: Discourse, deomcracy and design in the classical polis.

Funke, P. Western Greece.

Gaastr, J. Shipping sheep or creating cattle: domesticate size changes with

Greek colonisation in Magna Graecia

Gatzolis, C. The Europe of Greece: colonies and coins from the Alpha Bank collection.

Granser, E. Pithekoussai (Ischia): Colonisation vs Participation.

Kagan, D. The Peloponnesian War

Pericles of Athens and the birth of democracy

Kron, G. Archaeozoological evidence for the productivity of Roman livestock farming.

Lampadiaris, N. Syracusan Imperialism

Lomas, K. Greeks, Romans and Others: problems of colonialism and ethnicity in southern Italy.

Martalogu, A. Beyond the Greek and Italiote Worlds: A local Tarentine Perspective.

Miller, G. Arete

Oome & Attema, Hellenistic Rural Settlement and the City of Thurii.

Saltini-Semerari, G. Taranto before Magna Graecia.

Thatcher, M. Identity and politics in Greek Sicily and Southern Italy.

Various SNP genotyping elucidates the genetic diversity of Magna Graecia grapevine germplasm and its historical origin and dissemination.

Wonder, J. The Italiote League: South Italian alliances of the fifth and fourth centuries BC.

Transcription.

(please note that there may have been some changes during recording)

Hi and welcome, my name’s Neil and in this episode I’m going to talk about the Greek colonies in Southern Italy. The Roman writer Strabo referred to this region, and Sicily, famously as Magna Graecia or ‘Greater Greece’ due to the number of Greek colonies there and their influence. In this episode I’ll be looking into the history behind some of the colonies, how colonization manifested and a potted history of the colonies in Southern Italy from the mid 5th century BC through to the early 3rd century BC, where, well, I don’t want to spoil it.

Before I get stuck into it a bit of podcast husbandry. To start with hello, if you are a new listener welcome and for any existing listeners, brilliant, I really appreciate you coming back for more. You, yes, you, are my marketing. I’m a solo hobbyist indie podcaster with a full time job and the pretence of a social life.

I rely a lot on reviews and ratings, apparently these help drive the magical algorithms which then suggest my podcast to a wider audience. On Spotify you can rate the podcast as well as individual episodes. On most other platforms such as Apple Podcasts you can also review or rate. Alternatively just get the word out there to anyone you think might be interested. I’ve had some really nice feedback recently and trust me when I say it makes a big difference.

Episode notes will be on my website ancientblogger.com and this will include a transcription, maps and resources used and cited in this episode. On social media I’m ancientblogger on twitter, tiktok , youtube and instagram. And if email is your thing then I’m ancientblogger@hotmail.com. And just to shake things up this podcast also has its own twitter @houndancient.

Just a couple of final things firstly all these dates are BC unless otherwise stated. Out of habit I’ll probably say it anyway but just in case I don’t. Secondly sometimes there are different names for colonies, whilst I may reference these I’ll try to stick with one name to avoid confusion.

Ok then, here we go.

The story and history of Magna Graecia is one about colonies and this word needs some attention. The words colonies and colonisation carry with them a series of associations which are very specific to modern history. The Greek experience of colonies was different in a number of ways, for a start these weren’t mass movements of people orchestrated by an empire. Often they were small enterprises supported by a single city state. They were also non-military, the rationale behind them I will come to, but it wasn’t a military project there wasn’t an invasion. In fact more often than not it was a slow and steady trickle of people to an area which was known about and with the idea that the colony would knit itself into an existing framework of trade and resource.

There are instances of fighting, in fact that’s mentioned a fair amount later on. But where this takes place it’s more of a result of other dynamics in play as well as it being something which was often in occurrence regardless of who you were or where you came from.

The first question, and an apt one, when it comes to history is when? Well, colonies in southern Italy start to appear from the 8th century onwards and not just here. Greeks also had colonies on the Black Sea, in northern Africa and Siciliy to name a few other locations. They were also not the only other people to be doing this. The Phoenicians, hailing from modern day Lebanon were masters of the sea and set up numerous colonies across the Mediterranean as far as southern Spain. Possibly their most famous colony being Carthage.

So why were the Greeks doing this? Well the exact rationale has been debated, it was once argued that an excess of population drove the various Greek city states to start sending out colonists but this has been challenged as just being a convenient argument rather than a cogent one. The answer was probably a mix of opportunism and some social pressure. For example, a city state knows of a good site in southern Italy. It has access to good trade networks and possibly resources which would strengthen it as a parent city.

Now, within the city state might be those who would also benefit. Perhaps a farmer whose holdings are never going to grow and would welcome the chance to increase his holdings. Likewise a merchant who would welcome the chance to corner a market somewhere overseas. If you’ve listened to my episode on the Oracle of Dodona you might recall the questions asked there which relate to a new career or moving somewhere new. The point being that ancient Greeks perhaps moved a bit more than we might think.

All that was left was for the Delphic Oracle to give its consent and voila. As mentioned it doesn’t seem that we have large movements of people at a single point in time. A better argument might be that there was a gradual movement over a number of years.

There was also the wider political game between the Greek city states. Perhaps a rival city had a few colonies near to one of yours, so you might think about sponsoring another one nearby just to balance things up. This brings me to the link between colony and parent city. It was certainly an important dynamic as you’ll hear.

Thus far I’ve said ‘southern Italy’ a few times. But what do I mean by that? Well Magna Graecia is a loose term but we can think of it as covering everywhere south of modern day Naples. This generally included Sicily but in this episode I’m not going to include Sicily, it would just be too much to cover as well as everything else. But if people enjoy this episode I will endeavour to do one just on Sicily and the colonie there.

Southern Italy wasn’t empty, the idea of a colony in the middle of nowhere didn’t make much sense. The ideal colony would have internal trade routes and perhaps a people who were amiable towards the colony. Infact it could be that the colony itself mixed with an already existing local population. This would benefit everyone, the locals would have new resources brought in and the Greeks would have somewhere stable.

The site of Pithekoussai is a great example of this. Pithekoussai was most probably a settlement, a trading post rather than a colony, though there is a debate on this. It dates to the early 8th century BC, and Greeks from Euboea, an Island just off the Attic coast were those who were said to have settled there.

It was located on the island of Ischia in the bay of Naples and exacvations there have revealed a stunning variety of objects. A scarab from ancient Egypt with the name of the Pharaoh inscribed onto it, an ointment flask from Syria and, closer to home, Etruscan pottery.

Here’s exactly why you might want a colony or trading post in this spot. And the Greeks there brought their own skills to the table. Development in pottery enabled mass production of amphorae, this itself had a knock on effect. That’s because of the two main industries there perfume and wine and these took full advantage of this and both grew as a result of being able to export more of their respective products.

Consider the knock on effects this had both for non-Greeks and Greeks alike. More product meant more workers hired, the infrastructure which moved the goods would have been improved. The operational chain would have been extended and brought more people in thus building the economy further.

When the Greeks settled across the bay of Naples this technology continued to make an impact. The fast-wheel technique meant a better quality of product and more of it. Non-Greek peoples learnt this and were able to create a finer product which they could then export or sell to a growing class who could afford it. Previously only a small group of elites could afford to import fine pottery, now a greater slice of the population had access to it. And of the traditional style? Well, that wasn’t overriden – it continued to be made which is a good example of integration.

And it wasn’t just pottery itself but what was on it. Two items found at Pithekoussai had inscriptions in Euboean Greek, a variation of ancient Greek. One inscription on the famous cup of Nestor invited the drinker of the vessel to enjoy their drink, the other inscription was certainly contrasting. It stated “I am Tatia’s lekythos, may he who steals me go blind”. This is some of the oldest Greek inscriptions to have survived and it’s also the type which influenced the development of the Etruscan alphabet.

There are a few other good examples of Magna Graecia acting as a conduit for new ideas and practices. According to a study which is in the reading notes the domestication and cultivation of grapevines was added to by the Greeks in southern Italy who took different types and mixed them with existing varities. This was then pushed out to the western Mediterranean. There had been viniculture in the region, but the Greeks developed it further particularly in the types of grapevines used.

A similar pattern existed in respect of agriculture, varieties of Greek sheep imported were prized for their wool production. The practice of growing larger cattle was something else the Greeks introduced and which became a standard practice.

And of course there were the Roman baths. I’ve done an episode purely on this but it’s considered that the baths which Rome became famous for originated in Sicily and Magna Graecia was how Rome got hold of the idea and, well, the rest is history.

The Greeks in southern Italy certainly influenced the people around them and elsewhere. So where were these colonies exactly? Here are a few of the major ones and a bit about them

From Pithekoussai it is a hop, skip and watery jump across to the mainland, a journey of approximately 17km (10.5 miles) to what’s considered the oldest Greek colony in Italy. Cumae. Given its proximity to Pithekoussai it’s no coincidence that there was a relationship between the two. Pithekoussai was the founder, perhaps the growth on the island of Ischia prompted the Greeks to set up their own colony across the waves. This new colony was therefore Euboean and Cumae’s foundation date is given as 740. To put some context on that date the traditional foundation of Rome is given as 753 and 776 is the date for the earliest recorded victor at the Olympic games. A caveat for the latter is that 776 wasn’t the first Olympic games, to hear more on that then you can help yourself to an episode I did all about it.

Cumae must have been considered an old and important location by the later historians of Rome, Livy who wrote his history of Rome in the late 1st century had Rome’s last King, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, as living out his exile here. In more realistic history Cumae howed its international links when it sided with Syracuse against the Etruscans in a naval battle in 474 BC.

Cumae is also a great example of how a colony could become a parent to another colony, around 470 BC it settled Neapolis, probably in conjunction with an older settlement of Greeks there. This grew and later we know it as Naples.

Moving south and along the coast there were a number of other colonies such as Elea but it’s to the toe of Italy which we pause at and a colony called Rhegion. This was founded around 730 BC and by colonists from Euboea. Between Rhegion and Sicily are the straits of Messina which, at their narrowest point measure just 3.1km (1.9) wide.

It would be tempting at this point to head over the straits of Messina and talk about the Greek colonies there, however, as I mentioned earlier the Greek colonies of Sicily demand their own episode – so I’ll just give the briefest of summaries. Sicily was split largely between two factions, in the west the Phoenician cities which allied with Carthage. In the east sat many of the Greek colonies with Syracuse arguably the most famous. Syracuse became a major player in the western Mediterranean and you’ll hear later about how it got on and didn’t get on with the Greek colonies in southern Italy.

On the subject of strained relations if we were to head east along the southern coast of Italy and towards the arch of its foot we’d come to Locri. This was said to have been founded in 680 by Locrians from eastern mainland Greece. It was even said have had the first written code of laws provided by Zaleucus. As you’ll hear Locri wasn’t the most neigbourly of colonies.

Our next stop is further east along the coast and just before the arch of the Italian foot, this is where we find Croton. Founded in 710 by the Achaeans, a people from the northern region of the Peloponnese, it was a famous location for a number of reasons. This was where Pythagoras was said to have landed and where he developed his school and where Pythagoreanism started to talke hold. Don’t worry, I’ll get to that later. It was also the home of one Milo, possibly the most famous athlete of ancient Greece. Milo was a wrestler who won six times at the Olympic games whilst also holding victories at other pan-Hellenic games. His strength was legendary as was his appetite. He was said to have eaten 20 pounds of meat and 20 punds of bread each day, washed down with 8 quarts of wine (that’s seven and a half litres). At Olympia one year he carried a 4 year old bull around the stadium and then ate it later on. Bit of a gym brah I sense, just swap the bull for a large protein shake.

If we were to continue east along the coast we come to Sybaris and what a place it apparently was. Founded in 720 by Achaeans it became a byword for excessive luxury – in fact it the word ‘sybarite’ a person who is self-indulgent in their fondness for luxury comes from Sybaris.

In the 3rd century AD the Greek writer Athenaeus documented some of the opulence associated with the city and its residents. This included awnings covering roads, chefs being awarded crowns for their skills and even other chefs being banned from copying a recipe if it was deemed worthy. Horseplay took the form of just that, dancing horses taught to dance to the flute. This backfired when those horses in the Syrabite army fought one from Croton. When musicians in the opposing army started to play music the horses danced over to them with their riders presumably bemused by it all still atop.

Croton and Sybaris clashed and in 510 Croton defeated it in a battle where Milo commanded the army dressed as Hercules. There were continued clashes between these two cities as you’ll hear shortly.

Out final colony sits in the point where the arch meets the underside of Italy’s heel at Taras, later known as Tarentum. This was apparently founded by Spartans, or rather the illegitmate children of Spartan wives. One account has Phalanthos, the founder, as saved from a shipwreck by a dolphin and hence the dolphin became the symbol of the city. Taras had it all, probably the best harbour in southern Italy and abundant agricultural resources. It made use of these and as you’ll hear came to become a major colony

As I mentioned earlier there had been people prior to the Greeks arriving and these non-Greek peoples interacted with the colonies in different ways. There were the Samnites, hailing from the mountanous central south region. To the south of them were the Lucanians they occupied the central southern part of southern Italy. To their east were the Messapians and to the west, running along to the toe of Italy were the Bruttians.

What’s important to note is that there wasn’t a profound Greeks vs non-Greeks dynamic in play here. It wasn’t a case of us versus them. Non-Greeks fought with non-Greeks, Greeks fought with non-Greeks and Greeks fought with Greeks. Violence often belonged to a wider set of behavioural patterns, for example to settle disputes, rather than belonging to a Greek vs non-Greek axis.

Probably the best description I’ve come across in relation how everyone behaved towards each other was that it was directed by opportunism. The chance to raid, to enrich or seize strategic control of an area was really what drove many actions and outcomes. And any student of ancient Greece will recognise just how capricious Greek cities could be to each other. It was all of this this plus a bunch of non-Greeks acting in a similar way. It was a mixture of Mean Girls meets a Jerry Springer feuding family food fight.

Aside from making me feel old this analogy is quite apt because I’m going to kick off my brief history with the end of a long running feud between two colonies. As mentioned Croton and Sybaris had fought in 510 with Croton victorious. This continued through the early half of the 5th century with Sybaris suffering numerous defeats. Around 446 things came to a head and Sybaris appealed for help to the wider Greek community. Athens responded and sent settlers to reset things and hopefully prevent any more fighting. This failed to work largely because the Sybarites kept falling out with the new settlers. Eventually they left to found a new colony called Sybaris on the Traeis.

What followed next was an ingenious solution, the founding of a new colony called Thurii near to what had been Sybaris. It would also not be done by one or two cities but be a pan-Hellenic colony to showcase co-operation amongst the Greeks. The person behind this was an Athenian politician called Pericles. Nothing in this new colony would be left to chance, the layout of it was designed by Hippodamus who had set out Athens’ new harbour, the Piraeus. The philosopher Protagoras was said to have drafted the laws. Even the celebrities of their time such as Herodotus were added as founders.

Perhaps the idea of Greeks working together was a tad idealistic but it was needed, in the Greek mainland tensions were running high and within southern Italy Polybius wrote of sizeable unrest caused by Pythagorean communities. Pythagoras had been dead for some time but his followers had established bases in some colonies and these were not getting along.

The founding of Thurii had knock on effects. Taras wasn’t too happy with what it saw as a rival colony nearby. The response was for it to set up its own colony called Heraclea as a check and balance. But elsewhere other Greek colonies were starting to form up defensive positions. According to Polybius the colonies of Croton, Caulonia and the new Sybaris formed an alliance. The fact that new Sybaris had been created in part due Croton’s defeat of it and that they were now in a defensive alliance is a great example of how quickly relations could change.

This alliance, known as the Italiote League, is thought to have been formed around the 430s. We know little of it, indeed the genesis of it is given at a later point by another historian which I’ll come to later. All three founding colonies had Achaeans as founders and they followed an Achaean constitution in this new league. There was obviously a theme there. The formation of leagues and federations was a common thing in ancient Greece and it presumably made sense to form one at that point. The Italiote League, at least in this form is thought to have acted as a check against the likes of Thurii and other Greek colonies such as Locri.

It was also around this time that, to the east, the Peloponnesian War had started. This presented a raft of new challenges to the colonies there, how were they expected to respond to it? In some instances we can clearly see how the relationships manifested but also shifted. For example an Athenian force attacked Locri around 427, presumably in support of Rhegion which is where it had launched a force into Sicily from. However, in 416 Rhegion gave minimal assistance to an Athenian naval force on its way to attack Syracuse.

Presumably the colonies of the southern coast were indifferent about being drawn into a war on Sicily though some colonies such as Thurii and Metapontum did provide troops to the Athenians and Taras did provide some support to Sparta. At best though it was a passive obligation.

To the north the colonies were facing a different kind of threat. In the 420s Cumae and Capua was taken by Samnites. The colony of Poseidonia, itself settled by people from Sybaris was taken by Lucanians, and probably at this point renamed Paestum.

The colonies to the south didn’t have to wait long before they would come under attack, at least some of them anyway. By the end of the 5th century a new threat was developing from across the sea and from the island of Sicily. Here a tyrant named Dionysus had seized power. Dionysus’ background might have been underwhelming, he was apparently originally a clerk, but he was now in charge of what was a powerful city and seems to have had a talent for ruling. Just as an aside it was under him that Greeks in the western Mediterranean first started to build siege engines such as towers.

Dionysus’ main headache had been the Carthaginian cities on the west of Sicily. But other Greek cities on Sicily were still opposed to him. There had been Leontini for example and this had been backed by Rhegion. It’s important to remember how close Rhegion was to Sicily. It had sat on the shoulder of Syracuse for some time and supported rebellions against Dionysus. To soothe things Dionysus had sought a political marriage but this was snubbed by Rhegion. The realisation must have set in that there was only one recourse. War.

In the late 390s Dionysus launched an invasion with Rhegion as his main target. For Diodorus Siculus, a historian of the 1st century BC, this was when the Italiote league was formed. It was a coalition of Greek colonies against Dionysus. This contradicts the earlier date given by Polybius, however, there is a good argument which may explain this.

Simply put there were two versions of the Italiote League, perhaps separate or not and these related to separate challenges. The first version was a response to the growing power of Locri and Thurii felt by those Achaean colonies. The second, perhaps an offshoot or reorientation was to provide a defence against Dionysus.

As to who formed the second league, well we can be confident that both Croton, Caulonia and Rhegion were members. But not all Greek colonies were members, and in fact some were likely acting against the Italiote league. Take Locri, which had formed an alliance with Dionysus in 390, it may also have helped that Dionysus’ wife came from there. Likewise Taras, they had enjoyed close links with Syracuse for some time so were most likely indifferent, it was unlikely that they would have sent troops against the invading tyrant.

Dionysus also made an alliance with the Lucanians. Earlier I mentioned how alliances didn’t fall in line with the Greek and non-Greek axis. So here we have a Greek from Sicily making war on other Greeks whilst allying with non-Romans against said Greeks. And other Greeks sitting on the sidelines or offering support against a league of Greeks. Need a sit down, me too.

In the battle of the Elleporus River the Italiote League suffered a huge defeat against Dionysus. Rhegion then fell to him in 387 and in 379 Croton was taken as well. But Dionysus didn’t pursue any kind of empire building. In fact after his victory at the Elleporus river he had released all the captives he took. This points to a policy of stabilising the region and pacifying it of winning goodwill as wel las victories. Dionysus died in 367 but with both Rhegion and Croton out of the picture the leadership of the Greek colonies and presumably whatever form the Italiote League now took was up for grabs and Taras siezed the opportunity.

It was presumably under the auspices of the leadership of the Italiote League that Taras started to flex its military muscle. The first manifestation of this was hiring a mercenary army in 342 to counter the growing Lucanian influence in the area. Given the depletion of the Italiote league as a military force perhaps the Lucanians sensed an opportunity.

The choice of a mercenary army seems practical. Taras could afford it and the Italiote League hadn’t covered itself in glory in the military context. Added to this was the issue of citizen men who had the levers of power in their respective cities. This resource was worth protecting and Taras had known what might happen if a large number of them were lost. In the early 5th century it had suffered a defeat in which large number of the elites had died. This changed the social structure to the extent that it moved from being what must have been an oligarchy, to a democracy.

Better then to employ professionals who were better trained and whose loss wouldn’t be felt in the political and economic context.

The first mercenary hired was a King of Sparta no less. In 342 Archidamus III was called upon with a mercenary army to help counter the power of the Lucanians. His success was brought short when he was killed in battle in 338. Following this Taras employed Alexander of Epirus or Alexander Molossos. Alexander had pedigree, his nephew was Alexander the Great and he certainly shared his more famous namesake’s desire for empire building. Here then we meet a problem. What if the mercenary general you hire decides that southern Italy looks very nice, a perfect place to carve out a kingdom.

It’s been argued that nearly did. Whilst employed to defend Thurii agains Bruttians the mercenary general started to forge close links there. Tensions with Taras started to grow and rumours were that he planned to move the seat of the Italiote League to Thurii. Presumably here he’d conduct a court with Taras increasingly isolated. We’ll never know because Alexander was killed in 331. According to Livy (9.19) as he lay dying of his wounds he compared his own successes with that of his famous nephews and concluded that his nephews victories were easier as he had merely faced effeminate easterners. That’s a whole new level of bitterness right there.

Taras continued with their poor recruitment policy. The third mercenary hired at the end of the 4th century was the Spartan Cleonymus, another effective general but yet another one who was looking to create an empire. Diodorus Siculus commented that Cleonymus acted in a distinctly ‘un-Spartan’ way and an example given is the general gaining access to a rival city of Metapontum under the impression of a diplomatic visit before sacking it and taking 200 women as hostages. Eventually Cleonymus outstayed his welcome and was forced out though not without some effort on the part of Taras and more or less everyone else.

The latter quarter of the 4th century hadn’t just been a tale of bad recruitment on the part of Taras. Aside from some bad guests southern Italy was experiencing attention from elsewhere and this wasn’t from overseas. Another faction was making steps southwards, one which would become a huge influence in southern Italy. You guessed it, Rome.

It wasn’t that Rome was this brand new entity, it was more that it was one of a number of peoples, factions and cities to the north of the Greek colonies. There were many at this time. But in the second half of the 4th century Rome had started to expand to the south. It’s main concern and in fact we can think of it as a buffer, were the Samnites. As I’ve mentioned these people occupied the area north of the Lucanians. Rome had tried to expand into the rich lands of Campania, but needed to secure the Samnites first and this took the form of three wars which took place with them from the mid 4th century to the early 3rd century with the Samnites finally defeated.

This presumably had increased Rome’s reputation with the southern colonies. In 284 Thurii needed help with the Lucanians but rather than ask Taras it turned to Rome which duly agreed. There’s little chance that any of this occurred without the understanding of consequences. Thurii, as you’ve heard, wasn’t a huge fan of Taras so possibly welcomed the chance to do a bit of stirring. Rome also must have realised that it was overstepping the line. But that’s almost what you expect of it.

In 282 Thurii went further and requested more Roman support. The outcome was another Roman victory against the Lucanians, enhancing its reputation further, and a Roman garisson there. This possibly was more about keeping the pro-Roman nobles in the city safe as much as anything else but it was another real blow to the pride and reputation of Taras.

It wouldn’t be long till Taras could exact revenge on Rome, a small Roman fleet soon appeared near its harbour. Whether it had strayed off course or not mattered little, Rome had infringed on its territory and with only a handful of ships. Taras was quick to send out a naval force which intercepted and defeated the small Roman force.

Rome sent an embassy to Taras to discuss the return of the Roman prisoners this included an ex consul called Postimius Megellus. Throughout the visit the embassy was mocked, in particular its attempts to speak Greek. The coup- de grace was provided not by a Tarentine official, but by a drunk with the nickname ‘half bottle’. As Megellus walked past ‘half bottle’ emptied the contents of either his bladder or bowels onto the ex-consul’s toga. When Megellus returned to Rome war was declared.

Taras had no standing army and so they turned to their old practice of hiring experienced generals and mercenary armies. This time they chose a general who became famous and was instrumental in more ways that one. His name was Pyrrhus, he had a very credible career up until this point having fought in the Diodachoi, the Wars of the Successors, basically the fall out after Alexander the Great’s death in 323. His experience was in the east and he brough with him not only this but something which hadn’t been used before on the battlefield of the western Mediterranean, the war elephant. These were most likely the Asiatic variety and had been a feature of armies fighting in the Wars of the Successors, in fact Pyrrhus had been present at the battle of Ipsus in 301 where elephants had inadvertently played a crucial role. War elephants weren’t ever that effective, but they were expensive and so more of a statement unit in an army though as you’ll hear they were initially effective against Romans who had never encountered them and who nicknamed them Lucanian Oxen.

Pyrrhus’ campaign with Rome is a minisode in itself, perhaps I’ll put it on the to do list. But to summarise he fought Rome in three battles. In 280 he defeated them at Heraclea with his elephants causing chaos amongst the Roman cavalry, the horses were terrified of them. At Asculum in 279 he won again, though only just. Though the Romans were technically an amateur army they had the experience of fighting the Samnites as well as other campaigns so they were quite good. Pyrrhus’ mercenaries, though technically of a better quality, suffered from attrition. Rome could be defeated and then draw on more reserves. Interestingly a census done around 280 gave the number of citizens able to serve in the military for Rome at around the 270,000 mark. Something which would become a hallmark of Rome was that it could levy seemingly endless numbers of troops.

This attrition of Pyrrhus’ army in the face of this challenge was presumably behind Pyrrhus’ famous comment following his victory at Asculum “if we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans we shall be ruined”. This led to the term Pyrrhic victory, which is where a victory comes at a huge cost to the winner which almost negates the fact that it won.

Between the third battle with Rome Pyrrhus decided to take a contract from the Greek colonies on Sicily to help against the Carthaginian cities there. This he did and as a nice bit of trivia it was from this encounter that Carthage was inpired to start using elephants in its army. Though the species used was a smaller variety local to north Africa.

In 275 returned and fought a final battle against Rome at Beneventum. This time he lost, and with opportunities in the Greek mainland Pyrrhus decided to give up on Rome and pursue his ambitions there. Back at Taras there was garrison left by Pyrrhus and commanded by Milo one of Pyrrhus’ trusted officers. This initially supplied some stability but elsewhere in southern Greece the landscape was rapidly changing. In 277 Rome had taken Croton and Locris. By this point Rhegion too had a Roman garrison.

Taras seems to have stayed non-Roman mainly due to the garisson there but also because Pyrrhus may have realised how valuable it was. In 272 Pyrrhus was killed, his death was as eventful as his life. He had been besieging the city of Argos and attemped to sneak in a force which included an elephant. Yep, you heard that correctly. Stealth and massive pachyderms aren’t good bedfellows and soon the alarm went up which led to that thing an invading army always dreaded, street fighting. A few reasons why this is so, firstly the invading force don’t know the layout of the streets and are easily ambushed. Secondly you are often having heavy objects thrown at you from people on the roof. The story goes that an old woman landed a roof tile on the head of Pyrrhus which either killed him or knocked him out at which point he was killed.

Upon hearing this the garisson at Taras realised there was little point being there anymore and in 272 they negotiated a depature which allowed the Romans in.

It’s at this point which Rome had taken the key points of southern Italy and could claim it as certainly within their remit. But this didn’t mean it was all shades of Rome here, by the end of the century a certain Hannibal would be up to mischief here, trying to unpick the alliances Rome had and having some success. Rome’s conquest of the Italian peninsula is sometimes seen as an absolute thing, a conquest here and there resulting in immediate subjegation. But it was a much more gradual process than that and I hope what I have done is take you to the earliest manifestation of Roman control in the south.

I also hope you’ve enjoyed listening to how the Greek colonies manifested in southern Italy and the types of interactions which resulted. If you’ve enjoyed it – let me know, it’s always great to hear fom you. More importantly until next time, take care and keep safe.