When you think about tombs and curses the popular examples most likely involve pyramids and mummies (though this is rarer than you might think). However, in this instance we have a curse on a sarcophagus with links to Egypt but also far from it. I’ll be covering curse texts and curse figurines in an episode on my Ancient History Hound podcast and including this example. Here’s a bit more about it all.

Discovering Ahiram.

The discovery of the tomb of Ahiram was a joint venture between man and nature. In 1922 heavy rains caused a landslide at Jbeil in Lebanon and the result was the revealing of a single tomb. Following excavations by French archaeologists a total of nine tombs were found there, the earliest dating to the early 2nd millenium BC. These belonged to royalty, or at least rulers of the area which had been an important site for a long time. Though today we know it as Jbeil there is reference to it as Kbeny by the Egyptians as far back as 2,600 BC. Subsequent cultures had known it by other names, the Phoenicians of the 1st millennium BC knew it as Gebal, the later Greeks as Byblos. The find of tombs there wasn’t a surprise, but what they found in tomb V certainly qualified as one.

The three sarcophagi.

In tomb V three sarcophagi were found, two were very similar. These were of the same design and made of hard stone. The third was different, it was soft limestone and carried inscriptions which stated that this was where an individual Ahiram had been laid to rest by his son. However, it doesn’t seem that Ahiram had been the original resident of either the tomb or the sarcophagus. Those two stone sarcophagi had seemingly been the earlier inhabitants of the tomb. As for the sarcophagus? This was carved in an Egyptian style with Egyptian elements and has been argued as dating to the 13th century BC. Thankfully it had an inscription which named the person resting in it, an individual called Ahiram.

Ahiram’s curse.

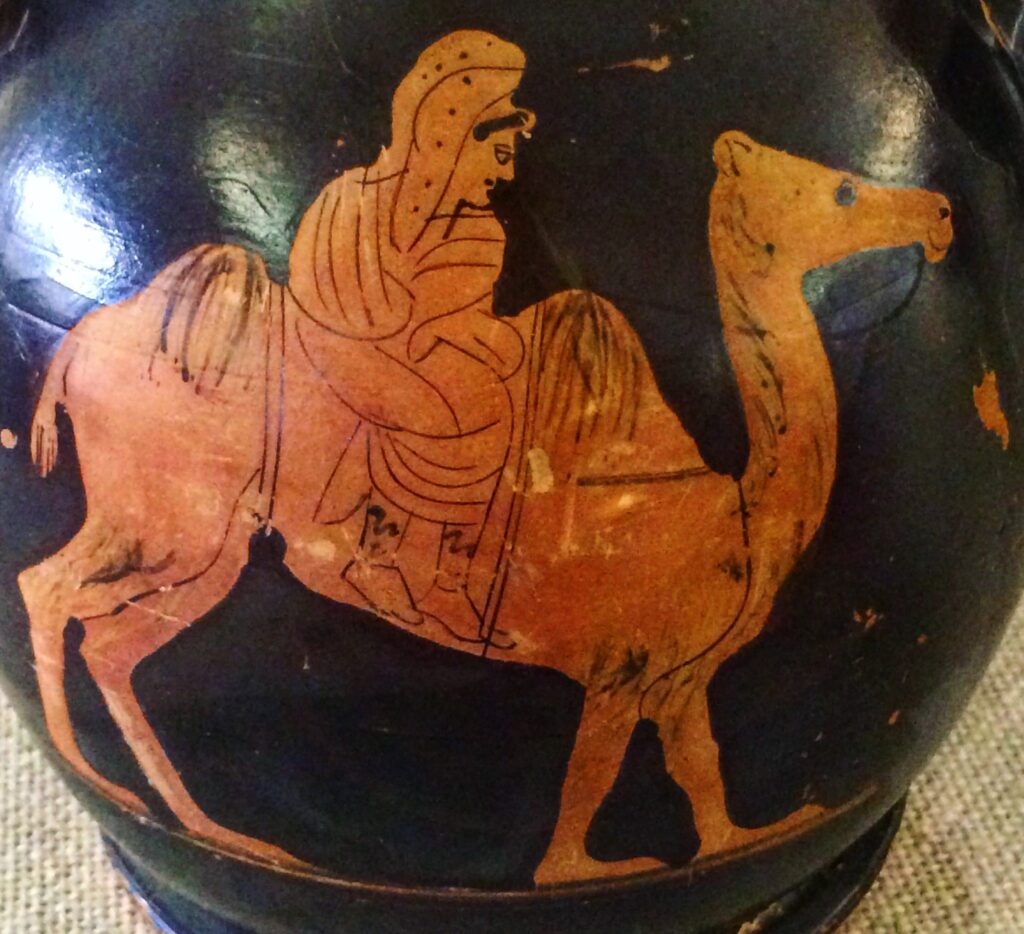

The sarcophagus features scenes, including women mourning and a generalised funeral procession. On the lid two individuals face each other and this has been argued as representing Ahiram and his son. This has fallen into a wider debate about representation on the sarcophagus, even to the extent that it didn’t represent the Ahiram at all but instead was a deity. The challenge here is to understand what may have existed on the sarcophagus prior to Ahiram, what was physically changed when he was placed inside it and what may have stayed but was reinterpreted and thus their original meaning shifted. It remains a subject of some debate.

Traces of paint were found which reminds us that many items we think of as drab in terms of colour were once vibrant things.

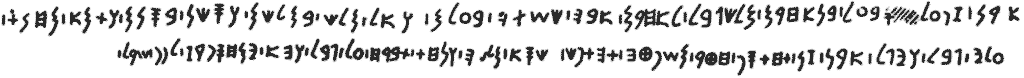

But it is the inscription on the sarcophagus which is considered as integral to Ahiram. It tells us that his son established this for his father and warned against any governor, commander of the army or king from disturbing his rest by moving the coffin (or sarcophagus, as this is a translation). If a person was to ignore this warning then they would face consequences. Their imperial sceptre would break and their throne would be overturned. The curse targeted the symbols of office and rule, as such this was one aimed at a king or ruler. Perhaps then this was about protecting the lineage and legacy Ahiram’s son was establishing. The curse ended with a warning to anyone who might damage the inscription, promising that his royal robe shall be torn. Was this a warning against anyone looking to negate the curse by removing the inscription itself?

The inscription named not only Ahiram but his son who facilitated it all, his name is translated as either Ithobaal or Pilsibaal. It would be unusual for a King to name his father and for this not to legitimise him in some way. As such it’s presume Ahiram may have been a king.

The dating of Ahiram.

The details surrounding Ahiram are sparse, as mentioned it’s unclear if he was even a king, though again it would seem logical that he was. The inscription does give us some information about him, a possible date. This was in Old Phoenician and has been agreed as dating to around 1,000 BC. This provides us with an approximate end date for Ahiram, assuming he was a king. Of course it could have been inscribed decades later, but at worst it gives su something and that’s vital because we have little evidence from which to build out a chronology of the Kings of Byblos. Establishing chronologies can be a torrid affair but sometimes small, almost irrelevant information, can be crucial. As an example the Neo-Assyrian King list was made possible through a note a scribe had made about an eclipse (read here for this and more on eclipses as tools to date with).

Moving back to the inscription, this could well be the oldest surviving example of Old Phoenician we have. Perhaps we’ll find more in the region, hopefully so, though I’ll settle for something less dramatic than a landslide to kickstart it all.

(featured image by Emna Mizouni)