Lupercalia – some notes.

I hope you enjoyed the episode on the Lupercalia. The promo I featured was with The Partial Historians – if you want to learn about Rome they are a great resource and you can find them on twitter and other locations (just check the link to their website).

In the episode I mentioned my episode on the Foundation of Rome. This was the start of a miniseries on the Roman Kings. Here’s a link to the first episode.

Images.

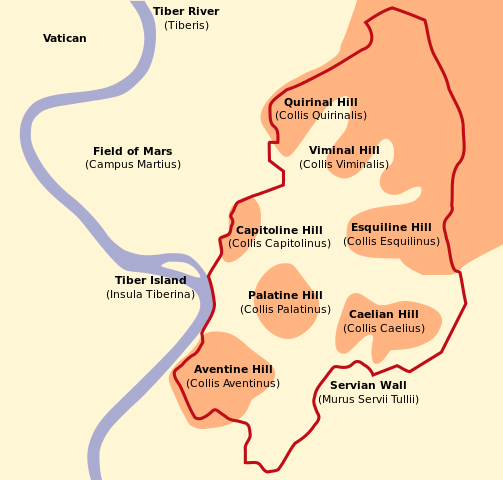

Firstly the Palatine Hill in Rome. You can find a bit more about the Palatine Hill and other Roman hills in a post I did about them: The Hills of Rome.

It’s always good to get acquainted so here’s a good map of the hills.

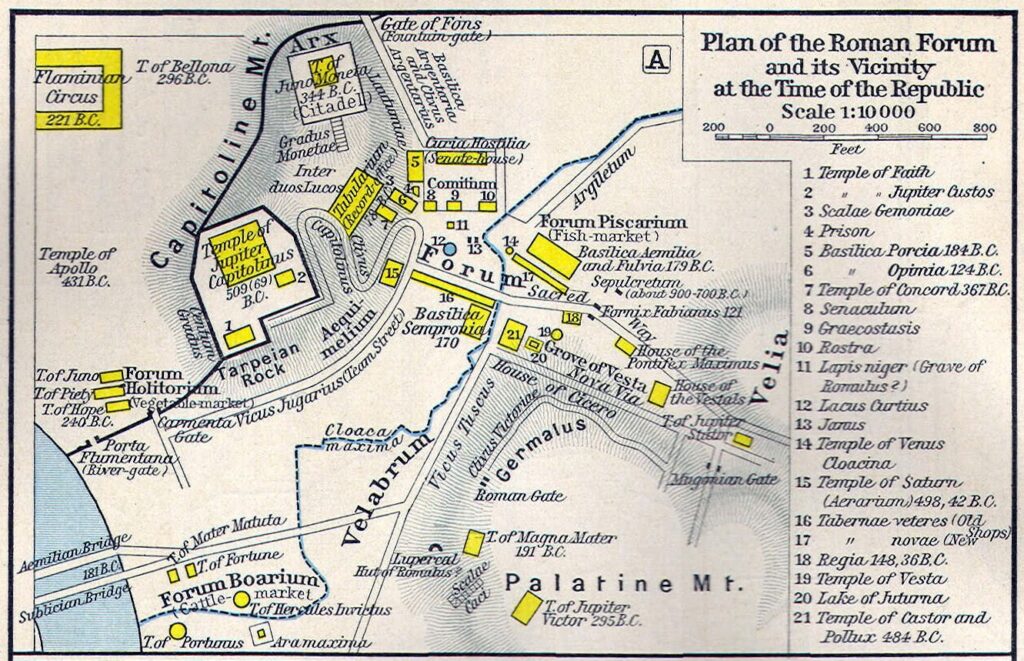

The map below gives a bit more perspective. It also gives the locations for the most likely route run by the luperic. In the bottom left of the Palatine Hill you can see the supposed location of the Lupercal. The luperci would have started here before heading east and then up to the Sacred Way (which you can make out to the right of the Forum).

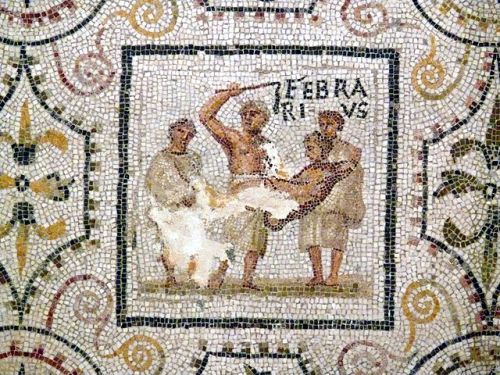

The representation of February in a 3rd century AD mosaic from Thysdrus in North Africa. Currently at the Archaeological Museum of Sousse.This is a great overview of the Lupercalia from Darius Arya.

Reading List / Sources cited.

Chandler, L. Ovid’s Fasti, Livy and the History of Rome from Romulus to the Gallic siege.

De Grossi Mazzorin & Minniti. Dog sacrifice in the Ancient World: A ritual passage?

Gillison, J. The Luperclia: suggestions for a near eastern mythological influence.

Guarisco, D. Augustus, the Lupercalia and the Roman identity.

Ionescu, DT. Amiculum Iuonis: Juno and the feast of the Lupercalia.

Scapini, M. Whipping in myth, ritual and magic practice: a case of convergance.

Tennant, PMW. The Lupercalia and the Romulus and Remus legend.

Vukovic, K. The topography of the Lupercalia.

Wiseman, TP. The God of the Lupercal.

Cicero. Philippics. Pro Caelio, Letters

Dionysus of Halicarnassus.

Dio Cassius.

Juvenal. The Sixteen Satires

Livy. The History of Rome.

Ovid. Fastii

Plutarch, Life of Romulus, Life of Caesar, Questions.

Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars.

Valerius Maximus.

Varro. The Latin Language.

Transcript.

Hi and thanks for joining me my name’s Neil and in this episode I’ll try to get to the bottom of what the Lupercalia was and how the Romans understood it.

Before I do the normal podcast husbandry bit, I need to thank Alicia. I had an email from Alicia saying that she really enjoyed the episode I did on the Saturnalia, so would I be interested in doing one on the Lupercalia? Well, here it is and thanks again Alicia. It’s always fantastic to hear from listeners so if you have an idea, just send it in.

You can find me all over the place, on twitter, instagram, youtube and even tiktok I’m ancientblogger. And this podcast has its own twitter handle of @houndancient. Don’t forget my website, it’s called ancientblogger.com and I’ll be posting episode notes on it for this episode. This will include the sources used, reading list, transcript and other content which I hope helps.

So -what should you expect? Well, I’m going to summarise what the sources made of the Lupercalia, in particular what they thought the origins of it were. I’ll also bring some modern perspectives which help us understand things. And then of course I’ll be recreating how it went and this includes one famous instance from Roman history which had the Lupercalia as its backdrop.

Right then, I’m going to begin by asking you to imagine the following scenario. You’re in Rome at some point in the first century AD, more specifically it’s February the 15th and you aren’t just anywhere in Rome. You’re near the foot of the Palatine Hill or perhaps in the Forum. There seem to be a number of people gathered around, something’s brewing. And then you see or hear them a group of young men running about naked and holding thongs made of goathide.

As they run past people they strike them with the aforementioned thongs. Rather than lead to a riot it’s actually encouraged and people seem to be happy with what’s going on. This was the Lupercalia.

By the time the Lupercalia was being literally run in the 1st century AD it was was considered old, very old – indeed as you’ll hear it was linked to the myth of Romulus and Remus with the sacrifice and starting point of the running located at the Lupercal. This was a cave outside of which the mythical twins were found by the she-wolf and suckled. The Lupercalia was therefore tied to events and places which, in myth, predated Rome’s foundation.

Our main sources on how the Lupercalia began are Ovid, Plutarch, Livy, Valerius Maximus and Dionysus of Halicarnassus. We have others such as Cicero and Varro also chipping in. All of these writers date to either the 1st century BC or later – straight away there’s an important point to be made.

And it’s that Rome was late in the game when recording or accounting for its history. Rome’s earliest known historian, Fabius Pictor, dated to the end of the 3rd century BC. To give some perspective that’s around the time Hannibal was fighting Rome in the 2nd Punic War.

It must have been a challenge, or more likely an impossibility, to find any contemporary sources which might explain the Lupercalia or provide insight into the whys and hows of it all.

And you know what? Far from being frustrating it’s fascinating. Because it feels as if the writers are trying to make sense of it all. By the time of their writing the Lupercalia was an established and important ritual. But no-one is sure exactly how it got there. But they each had their ideas and observations and I’ll try to summarise what those were.

I’ll start with possibly the most famous account of the Lupercalia by a poet called Ovid. His very long poem, the Fastii detailed the Roman festival calendar and gave descriptions on each festival. As it was a poem there was a need to entertain, this wasn’t a dry account, and what Ovid wrote about the Lupercalia and how it began is stocked with action. Most of it nude.

It starts with Romulus and Remus as young men who are not aware of their background or calling, at this point they are are simple shepherds and attending a sacrifice to the god Faunus who is linked to the Greek god Pan.

As the brothers exercised naked, by the way Ovid is all about why the participants in the Lupercalia, the Luperci, run naked, the alarm is raised. Rustlers are making off with the cattle and so Romulus and Remus launch into action in their respective birthday suits. They split up into two groups with Remus and his group returning with the cattle and Romulus and his bunch returning empty handed.

This part of Ovid’s poem goes some way to explaining all that nudity, it’s because the twins had been caught out whilst exercising. But Ovid also supplied more information about where it happened, the inclusion of the goathide thongs and their function.

For Ovid the Lupercalia was linked to the Lupercal – a cave – which was found at the foot of the Palatine Hill. It was outside the cave where the basket containing the twins came to rest after the floodwaters receded and it was here that the she-wolf found and suckled both Romulus and Remus. This link and the importance of the cave seems to be universally agreed upon by the way and as you’ll hear it formed the starting point of the Lupercalia.

As for the goathide thongs and why you would want to use them to hit people, well, this was given a secondary explanation – separate from the story of the twins chasing their cattle. Ovid wrote that when Romulus was king there was a fertility crisis at Rome. Help came in the form of Juno, a Roman goddess who spoke from a sacred grove. Her instruction was “let the sacred he-goat pierce the Italian wives” and yes, that doesn’t sound good. Luckily an augur, a type of priest was available to demonstrate what this meant in practice. After killing a goat he made thongs from its hide and used these to hit the women their on their backs. This fulfilled the godly prescription.

Ovid’s account of the Lupercalia therefore provided a rationale for many of the elements which formed the Lupercalia of his day, he was born in the mid 1st century BC and died around AD 17. There’s the nudity, the running, the goathide thongs and using them to hit people. But these aren’t presented as one single ritual, the running and nudity have their own origin story and the thongs and use of them have their own. There seems to have been initially separate rituals and this is an important point to note. There’s also a heavy element of the foreign, or non-Roman. Ovid mentioned Pan and the link to Faunus. He also included a character called Evander, not a Roman but a Greek from the region of Arcadia. In fact the worship of Pan was prevalent here. And finally, that augur, the priest who interpreted the words of Juno…he’s describe as hailing from Tuscany, or Etruria – the Etruscans having a big influence in Rome. Particularly in the accounts of the early kings of Rome – and if you want to hear more about that you can find my miniseries on the foundation myth of Rome and its kings.

Our next source to consider is Plutarch. He was a Greek writing in the 1st century AD and is famous for his Lives which featured famous Greeks and Romans. His account of the Lupercalia sits in his Life of Romulus, but he also mentioned it in his Questions.

Plutarch saw the Lupercalia as a festival of purification, this due to it being held in February and more on that later. He linked it with the location of the she-wolf nursing the twins, noted the association with the Greeks through the figure of Evander. These seem to be agreed elements. But he also had questions.

For example, he’s not exactly sure how the name of the festival linked to what went on exactly. It was named after wolves, and is linked to the site, the Lupercal, but how did that relate to what went on during the festival? He also included some much needed detail about what happened during the ritual.

The priests, after sacrificing the goat, touched the foreheads of two youths with the bloody knife. The stain was then wiped off with some wool dipped in milk. As to what happened next he commented that young married women were very happy to be hit with the thongs as it promoted both conception and a healthy birth.

Plutarch also included the thoughts of earlier writers. One, a character called Butas, reasoned that the blood on the forehead represented the peril Romulus and Remus were in that day whilst the milk represented the she wolf who had suckled them. As for the hot topic of nudity Caius Acilius had concluded that the twins had made their chase naked so they wouldn’t get too sweaty. Hmm, try that in court. But Acilius did think that the sacrifice of a dog, which occurred at the Lupercalia was because dogs were enemies of wolves and that it was borrowed from the Greeks who also sacrificed dogs in the context of rite of purification.

Dionysus of Halicarnassus, another Greek source from the 1st century BC placed the figure of Evander as the main influence to all of this, and it was even noted that the Palatine Hill was named after Pallenteum, an Arcadian city. It was at the foot of the hill that Evander built an entire settlement, all of this before Rome, and had even completed a temple to Pan near to the Lupercal.

On a wider point Dionysus often linked ancient Greece with the formation of Rome. He sees Greeks everywhere. Yet in this instance he’s not the sole advocate, the association of Evander and Arcadia to the Palatine Hill and the proto-Lupercalia is found even within the most ardently patriotic of Roman writers.

A good example is Livy who famously wrote about the history of Rome towards the end of the 1st century BC. He also had Pan and Evander as the main influencers to it all. Livy did change the story concerning the twins, rather than some cattle-rustlers this was an ambush with Romulus able to fend off the attackers but Remus being taken hostage. This is a crucial plot point because in the myth of the twins and the founding of Rome it’s this event where both are told of their parentage and so begins their quest to avenge their grandfather Numitor.

Finally there’s the account given by Valerius Maximus. His description of the foundation of it seems to mediate some of the previous points. I’ll read it out:

The custom of the Lupercalia was begun by Romulus and Remus, at such a time as they were making merry, because their grandfather Numitor, king of the Albans, had permitted them to build a city in the place where they were brought up, under Mount Palatine, which Evander of Arcadia had consecrated, by advice of Faustulus their foster-father. For thereupon they made a sacrifice, and having slain several goats, and eaten and drunk somewhat more than usual, they divided up their pastoral band, and girt with the skins of the sacrificial victims they sportively struck the bystanders

Valerius described the original Lupercalia as much more akin to what the Lupercalia was in his day, the early 1st century AD. Unlike Ovid there isn’t a separate rationale for the whole business with the whipping. It’s all part of the main festival. As an explanation for it all comes in one tidy package, a bit like the celebrants perhaps.

The sources all provide their understanding of the Lupercalia and how it had originated and there are some basic elements which seem agreed upon or at least not overly contradicted. Firstly, this was an old festival dating back to one founded by Romulus and Remus or one they participated in and was linked to their nursing by the she-wolf. Secondly it had strong links to ancient Greece and finally it had a geographical location – the Lupercal a cave on the foot of the Palatine Hill. I appreciate these are very broad basics – but you have to start somewhere.

There are gaps with some sources offering information which the others don’t. There are also differences, which you might expect. But there is also a contradiction sitting at the heart of the Lupercalia – how did any of the goings on at the Lupercalia relate to the name of it. In other words, what’s any of the Romulus and Remus myth got to do with running around whipping people and what’s a fertility ritual doing in a month where purification was considered the overarching theme.

I’ll start with the latter point. One possible solution is an argument which posits that the Lupercalia was originally a festival of purification and that at a later date the fertility element was added and this took hold, eventually becoming the main event.

The Roman name for a ritual concerned with purification was lustratio and though these rituals varied there are certainly elements of it which can be found in the Lupercalia. As an example take the procession which marked out an area. Far from dour occasions these involved chanting, music and dance with the participants carrying instruments of purification. Then there is the month of February, named after Februus a deity associated with purification but also fertility. And here we might pick up on that link with Juno because she was also known as Juno Februata. Sadly the sacrifice of dogs was also common in purification rituals. They were also often a sacrificed to the Underworld deities and the Lupercalia sat in the middle of a wider festival called the Parentalia which involved placating the dead. It’s easy then to consider the Lupercalia as a purification ritual or emobdying many elements and assocaitions of it.

Where the fertility element to the Lupercalia came in is intriguing. A fragment of Livy stated that this was introduced to the Lupercalia in 276 BC as a response to an outbreak of stillbirths. As with the Saturnalia the idea of introducing new elements to a festival wasn’t uncommon in Rome. But we might also pick up on the involvement of Juno. In Ovid’s account it was Juno who advised the Romans what to do as a result of the fertility problems and which culminated in the whipping.

It’s plausible that this was a later addition to the Lupercalia, but it could also have been an element of the original ritual which itself was rebranded. Initially the whipping was part of the purification ceremony as an act which drove away bad spirits or had a similar function. But it could also feature as a fertility ritual and this association gradually grew and became the main one for this activity.

But what’s the link with Romulus and Remus exactly? Well, it’s not exactly clear. Valerius has the twins as the founders but the other sources tend to associate the twins with an existing festival – one which served as a backdrop to their nude heroics. The main link is of course the location for the Lupercalia, the starting point at the Lupercal.

And there’s also another position to consider on this – that the Lupercalia was a mix of an original lustratio performed in early Rome and the myth of Romulus and Remus which may have been a later addition and was therefore grafted onto it. This might sound bizarre, surely the Romulus and Remus myth should be the oldest element in all of this. Well, their myth can’t be evidenced much before the 4th century BC.

Perhaps, and just perhaps because this is all speculation, there was originally a lustratio ritual in early Rome. It was celebrated in mid-February which made sense given the theme of that month being purification. But it was changed and had two big developments. One was the rise of the myth of Romulus and Remus which became standardised as Rome’s foundation myth. What happened next was a bit of retrospective continuity and so their story was attached to the lustratio and perhaps the name Lupercalia restulted. Either way the important thing was to have an association of the twins and that ritual.

Then there was the fertility ritual. The whipping may have been part of the original ritual and functioned to drive away the bad spirits but it then took on a new function, promoting fertility. Alternatively the whipping was just added in as a new part of it and so we had a new type of festival.

All of this is speculative especially given the gaps in our knowledge. But fear not I’m going to move from the hypothetical to the practical and describe the festival. Before I do here’s a quick word from the Partial Historians.

If you are interested in Roman history – go find them. It’s that simple.

Where was I , yes – What would the festival have been like by the Imperial period and what was that famous incident?

On the 15th February two groups of selected individuals would have congregated at the lupercal. These were the Luperci, the naked young men participating in the ritual. These were sub-divided into two groups, the Fabiani and Quinctiani. These represented the two groups who had joined with Romulus and Remus in their chase of the rustlers, the Fabiani had followed Remus and the Quinctiani joined with Romulus. It’s worth noting that this was a ritualised race so there wasn’t a requirement to be the quickest. After all this festival was all about audience participation.

At the Lupercal a dog and goat would have been sacrificed and a member of each goup had their forhead symbolically marked with the sacrificial knife. It’s possible there was a small feast or it took place later but we know what happened next, the two groups of men set off.

The exact route the luperci took isn’t clear but it is linked to two places, the Forum which was just to the north and slightly west of the Palatine, and the Via Sacra or Sacred Way. This wasn’t a random route and it’s thought that it represented an original one which marked out a boundary, it’s probably one of the few consistencies in all this that we have. The generally accepted route is that the luperci headed east, in an anti-clockwise fashion around the Palatine Hill before joining the Via Sacra just to the north of it. They then headed west following it to the Forum. Along the way the luperci would stop to hit people, or whip them.

Juvenal mentioned them tapping the hand of modest young ladies but perhaps things could get a bit more, let’s say, dynamic. There is a mosaic which dates to the 3rd century AD found at Thysdrus in modern day Tunisia. It’s called the mosaic of months and each month has its own image, February’s is a man wearing an apron holding a whip above his head. In front of him a woman is held by two attendants with her back exposed. This in fact links closely with Ovid’s description where following Juno’s instructions and the augur’s interpretation of it – the women were struck on their backs.

Perhaps this was a more formal or idealised representation of the whipping, but enough about that, back to the running albeit with some whipping.

It’s thought that the route ended at the Forum, but it has also been argued that the runners then headed back to the starting point. In either case the Forum and the Lupercalia in 44BC was the backdrop to a very famous event. It was here that a certain Julius Caesar was sat watching the goings on. And then a runner appeared holding a diadem, sometimes referred to as a crown. This wasn’t any runner though, it was Mark Antony, Caesar’s right hand man. What happened next was pure political theatre. There was a tension, the diadem symbolised absolute power the type Kings once had at Rome. That didn’t end well hence the whole Republic thing. Caesar, perhaps sensing the lack of support refused the diadem. The crowd broke into applause. Antony repeated the offer twice. Each time it was offered there was only the merest smatterings of applause, in contrast with each rejection the crowd broke into loud applause.

Of couse none of this was in any way spontaneous. Perhaps Caesar wanted to guage the reaction of the people, had they cheered when Antony offered the diadem then perhaps he would have sought to make himself a king of sorts. But the negative reaction had consequences. Those who had initially applauded the offer were led off to prison by two of the tribunes. Whatever the intention had been there was no doubt as to how this type of power grab would be viewed by the Roman people. It had been firmly rejected.

Mark Antony had run in the Lupercalia not as one of the original two groups the Quinctia and Fabiani. He ran as a newly created third group, the Juliani. You guessed it, Caesar had included his own family name as a new addition and he wasn’t naïve when it came to the politics of the spectacle so we can draw from this that the Lupercalia carried some weight, not only as a spectacle but something within the marrow of Rome. As an aside the Juliani group seems to have been abandoned after Caesar’s assassination which is not reall that suprising.

Another Caesar, the first emperor of Rome, Augustus also involved himself with the festival. Exactly what this entailed isn’t clear though Suetonius remarked that he prohibited young boys from running in it. This has been considered as Augustus giving the festival a cleaner image, but it might just be the practicality of it. Augustus often had his eye on how public festivals might be used and so limiting the participation of the Lupercalia may have been benficial to him in some way.

In the later periods participating in the Lupercalia became strongly associated with the Equestrian class in Rome. Perhaps there was an expectation that if you were to make anything of yourself you needed to have been a participant. But like any race or naked rambling with a goathide thong there is always an end. But the end of the Lupercalia wasn’t as immediate as you might have thought. When Christianity came to become the ruling religion in Rome you may have thought that the Lupercalia was on short notice. But no. It stayed as a festival till around the end of the 5th century AD irking a good number of Popes. When a late 5th century Pope (Felix III possibly) tried to abolish it a senator stated that this helped prevent pestilence and famine. So we’d best leave it in.

One final point about the Lupercalia is the association with Valentine’s Day. I’ve not come across anything which supports this. I’m not really sure how this festival links in, a group of naked men holding goathide thongs doesn’t immediately come to mind when I think of romance. But hey, each to their own – it’d certainly make a good rom com.

And on that note this brings me to the end of the episode. I hope you have enjoyed it – don’t forget to rate or review if you can and till next time keep safe and stay well.