I hope you enjoyed the episode, there were certainly many elements of it which I felt easier to identify with. Just in case you wondered there is a short piece here on the Saturnalia. You also heard from the Partial Historians – a great podcast if you aren’t already listening to it. In the episode I referred to the episode I have done on the Haloa – why not give it a listen? It seems the peoples of ancient Greece and Rome really let go in midwinter!

As mentioned here are some resources which I hope you find useful, chief amongst them was Martial’s present list in Bk 14 of his Epigrams.

Maps / Images.

The Temple of Saturn as it now stands, these remains are of a more recent construction than the one which was first involved with the Saturnalia in the early 5th century BC.

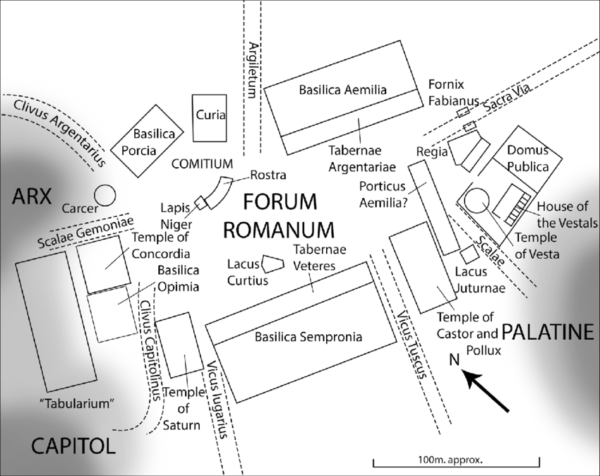

The map below plots where the temple stood (bottom left). The central public space of the Forum would have been ideal for the large feast.

The below image is a fresco from Pompeii which depicts Saturn holding a sickle (this links to his association with agriculture).

Gaming with dice was very popular, you might remember my trip to Richborough Roman Fort where I came across a Roman dice tower (to avoid cheating). Below is another fresco from Pompeii, this time gaming, most likely with dice.

Reading list.

Athenaeus. The Deipnosophistae.

Aulus Gellius. Attic Nights.

Cato. On Agriculture.

Catullus.

Cicero. Against Cataline.

Livy. History of Rome.

Lucian.

Martial. Epigrams

Pliny. Letters.

Seneca. Moral Letters.

Statius. Silvae.

Tacitus. Annals.

Beer, M. Guess who’s coming to dinner?: the origins of the lectisternium.

Bierl, A. Passion in a stoic’s satire directed against a dead Caesar?

Dolansky, F. Celebrating the Saturnalia: Religious Ritual and Roman Domestic Life.

Johnston, A. Vergil’s conception of Saturnus.

Mira Seo, J. Statius Silvae 4.9 and the Poetics of Saturnalian exchange.

Saturnalia episode transcription.

Problems with presents, shouting and parties. Join me as I talk about the Saturnalia on the Ancient History Hound podcast.

Hi and welcome, my name’s Neil and in this episode I delve into the Roman midwinter festival of the Saturnalia. I’ll be looking into its origins and what the main elements of it were, including what was changed and added. There are some very interesting features of it such as giving presents and I’ll be unpacking what you might get, what you might want and the whole present buying conundrum. Yep, it does feel quite contemporary at points in this respect.

Before I start just a couple of things. Firstly, this is an updated version of an earlier episode I did several years ago I have since deleted, in short I listened back to it and realised that there was a lot I missed out, or rather I could add. Secondly, there will be episode notes on ancientblogger.com and these will include a transcription, images, sources used and other information which I hope is helpful.

I’m on social media, ancientblogger on X, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok. This podcast has its own account on X as well, @HoundAncient.

Finally, thanks for the reviews, they mean a lot and I genuinely mean that. I create this podcast purely because I love talking about ancient history, I work full time and this will only ever be a hobby. Reviews not only help with the magic algorithms, in case you didn’t know I don’t have a marketing budget, they fill me with more vim to get the next episode done.

So if you have the chance to leave one on Spotify, or Apple or the platform you listen to then please do. If you want to say hi then find me on those social media accounts or go old school with an email to ancientblogger@hotmail.com.

Right then, I’ll begin.

The Saturnalia was a Roman festival which was celebrated in the depths of winter. December 17th is often given as the starting date of the celebrations which varied in duration as you’ll hear. By the 1st century AD we have a festival which included feasting, drinking, wearing bright clothing, giving presents and giving slaves the day off. Oh, and shouting Io Saturnalia a lot which can’t have become annoying at all.

However, in order to understand what this was for and how it had come about we need to leave Rome and head east to Greece. It was here that the Kronia was celebrated, this took place in Attica during the summer and it was a day where masters sat at the same table with their slaves and feasted. The Kronia was held in honour of the Greek deity Kronos, the father of Zeus who, even for Greek myth was a complicated character. Possibly the main myth you may have heard about him was how, after hearing that one of his children would usurp his rule, ate them and thus kept them imprisoned in his stomach – these are gods after all. One of his children, Zeus was hidden from him and avenged his siblings leading to the downfall of Kronos and the rise to power of the Olympians with Zeus in charge.

Anything involving a feast with Kronos associated might seem ironic, or even, pardon the pun, in bad taste. But the communal eating was about slaves and masters being considered equal and this tapped into another myth about Kronos. After usurping his father he ruled in a time called the Golden Age. It was a time of plenty where everything was easy and everyone was equal. At the Kronia this was symbolised by the slaves being treated as equals. There was also another association, agriculture. Kronos seems to have been linked to this, in fact this shouldn’t be that much of a surprise. Growing crops and harvesting was fundamental and other gods were linked in to this vital part of life.

Though the Kronia was an Attic festival there were other festivals held in Greece where slaves were allowed to participate as equals. Carystius of Pergamum, who wrote in the second century BC, noted a festival to Hermes on Crete where slaves were served by their masters. He also commented on a festival in the Peloponnese which lasted several days and on one day of it masters served their slaves and slaves even got to play dice.

Finally, going further east there was a festival at Babylon, which according to Berossum who wrote in the 3rd century BC involved slaves commanding their masters and even one of the slaves made master of the house. This element along with the playing of dice is worth noting for later.

As a concept then the idea of a festival where slaves were temporarily freed or given rights wasn’t uniquely Roman. Instead, and as you’ll hear, Rome formed its own version of this type of festival and it seems that the Greek influence upon it was strong.

Where the Kronia was named after Kronos the Saturnalia was likewise named after a Roman deity Saturn. Now, it’s not as simple as saying that Saturn was the Roman version of Kronos though there are often shared narratives when dealing with Greek and Roman mythology. Instead Saturn certainly became his own god and one particularly associated with Rome and agriculture. In Roman myth he emerged as someone who travelled to Italy as almost a mythical King / Farmer combination. Helping mortals understand agriculture and presiding over a golden age there. He certainly feels very different from Kronos and by the Imperial period he had his own mythology which was really quite distinct.

A very reasonable question you may have is why you’d have an agricultural deity celebrated in the depths of winter. Well, the reality was that this point in the agricultural year was crucial and not just for Rome. There is an episode you can listen to where I discussed the ancient Greek festival called the Haloa which was held around the end of December. This was in in honour of Demeter the Greek goddess of agriculture and the premise of it, much like the Saturnalia, was to ensure good relations with an agricultural deity which would manifest in a good harvest in the spring. We can easily think of the summer as when things grew in ancient Greece and Rome, but the reality is that in the height of the Mediterranean summer isn’t particularly condusive to growth. Those dark winter months, after the sowing in the autumn was when the real action was taking place. Exactly the time you wanted to appeal to the necessary agricultural deity.

In terms of when the Saturnalia started it’s difficult to tell. Mainly because Romans didn’t have their historians till the 3rd century BC and after. Livy, who wrote in the late first century BC did provide a date and a reason. According to him it was first set as a festal day in 497 BC when the then new temple of Saturn had been dedicated in the Roman forum. It’s notable that the festival was seen as inherently linked to the temple and possibly because to Livy this made sense. Though of course it’s possible that the Saturnalia existed before this in a more basic form akin to the Kronia.

What is also important to consider here is that Livy is placing it in the distant past from when he was writing about it. In a way whether or not one was held in 497 BC is here or there because Livy felt it needed to be at the earliest times of Rome. Remember that Rome had only become a Republic according to tradition in 509 BC. The dedication of the new temple to Saturn and the Saturnalia were early developments in Rome’s new Republic.

The early form the Saturnalia took was most likely a simple feast with slaves sat with their masters. However, this changed in 217 BC. For those with an ear for dates you might recognise this as during the 2nd Punic War, when Hannibal had marched into Italy. This is true and in a way the change made related to him, but not directly. Let me explain. In 217 BC Rome found itself at difficulties in dealing with Hannibal. In December of 218 BC it has suffered a defeat against him at Trebia, this meant that the new consuls who would take charge in March of 217 BC would have Hannibal top of their to-do list. This was a near perfect opportunity for either to win fame and fortune. An aspect of the Roman political system was that a consul only had a year to become as famous as he could. Being able to save Rome from an enemy general on Roman soil would guarantee everlasting fame.

In the spring of 217 BC two new consuls lined up to take respective armies against Hannibal. One of the consuls was Flaminius and he was, let’s say very over eager to meet up with his army and win that battle. So much so that he avoided undertaking the essential rituals a new consul needed to take before he could do such a thing. He managed to sneak out of Rome and meet up with the army nearby. The Senate was horrified, this was highly impious and they even sent a messenger to demand Flaminius return. But of course he didn’t. He did meet up with Hannibal at Trasimeme in the summer of 217 BC and fell on the battlefield along with most of his army.

Livy recorded in that year a number of portents were seen which caused even more alarm at Rome, the implication being that the gods were not happy with how Flaminius had conducted himself. The solution which was proposed was to include a ritual at the Saturnalia later that year, a ritual called the Lectisternium.

This wasa Greek ritual which involved placating the gods by having them join you at a feast. This was facilitated by having votive images of the gods placed on a couch which was carried to the feast. The idea being that you would improve relations with them. Though it might have been a new element to the Saturnalia it wasn’t new to Rome. In 399 BC Livy recorded that it had been used to placate the gods during a pestilence. It’s also an interesting sidenote to how adaptive Roman customs could be to external cultures such as the Greeks.

Rome didn’t just change what formed the Saturnalia, the duration of it was also tinkered with. There’s evidence that by the 1st century BC it was seven days, under Augustus this was brought down to three days. By the time of Claudius in the mid 1st century AD it was a five day affair.

During the Saturnalia all official business was closed, no courts, no Senate no nothing. Rome certainly committed to it and you might now realise how important it was to Rome and why, as I mentioned earlier, Livy was so keen to have it as a very old Roman tradition. As undoubtedly important and popular it was the irony is that we don’t have a single comprehensive description of one. What we do have are various sources often commenting on a particular aspect, the noise of the streets or, as you’ll hear, the politics of presents.

What I’m going to do now is give a brief outline of how a Saturnalia may have been in the 1st century AD using some of those sources. I’m also going to unpack some of those elements futher, the issue of slaves being freed for example. Before I begin here’s a quick word from the the Partial Historians, long time friends of the podcast and very apt for this episode.

Thanks to the Partial Historians there, I’m hoping to appear as a guest on their podcast to talk about the book which I will be downloading soon. Anyway, back to the topic in hand.

At Rome the Saturnalia began on the 17th of December, or thereabouts, with sacrifices to Saturn at his temple and then attention moved to the statue of the god himself. Woollen fetters or bonds which surrounded the statue’s feet were loosened. Symbolically this released the god in some context, possibly to invigourate the fields or enjoy the large public feast which then took place. He wasn’t the only god invited though as this was when the lectinsternium took place.

The early part of the celebration was held within the context of the public. It was a public sacrifice and a public feast. In the days following no official business was conducted as mentioned earlier and this was a possible vulnerability for Rome. With the Senate unable to react it did leave a window of opportunity for nefarious activites and one big near miss for Rome was something called the Cataline conspiracy. This involved a character called Catiline attempting a coup in 63 BC. Though it failed it was allegedly to be sprung during the Saturnalia when everyone’s attention was elsewhere and the machinery of state was suspended albeit getting well oiled as my nan would say.

The Saturnalia transformed Rome into a backdrop of partying and a lot of noise and even before the festival kicked off the city as a buzz. Seneca commented on this in the 1st century AD when he wrote, and I quote: “It is the month of December, and yet the city is at this very moment in a sweat. Licence is given to the general merrymaking. Everything resounds with mighty preparations”. He also referred to the ‘liberty capped throng’. This was a reference to the felt cap worn at the time, the pileus which was traditionally worn by slaves when receiving their freedom. It became a popular choice of headwear furing the festival.

The Saturnalia look didn’t just reside on what you wore on your head. The formal toga or even smart tunic was ditched for the sythesis a multi coloured robe. Martial, who you’ll be, hearing about a lot more later on, wrote about a character called Charisanus who still wore the toga at this time and an argument I’ve read is that this was ironic. Saturnalia had a chaotic and subverise motif, so why not do so by not conforming to this rule. Perhaps wearing a toga when you shouldn’t have was the edgy thing to do.

The Saturnalia didn’t just have its own outfits, it had its own shout. The cry of “Io Saturnalia” first became a thing when the lectisternium was introduced in 217 BC, at least according to Livy. This in fact gained a comedic connotation which I’ll come to later. By the 1st century BC the festival had become highly popular, or at least Catullus, a poet of the day thought so when he referred to it as the best of days. In the Imperial Period emperors might use the Saturnalia to win popularity. Statius, a Roman poet of the 1st century AD wrote about a sumptious Saturnalia under the reign of Domitian where games were held which involved races, women gladiators and both nuts and treats being distributed to the public.

As well as the public feast and street parties there were the private parties. And at this point I need you to imagine just how varied these may have been. For example, a Saturnalia party hosted by a rich Roman must have been a chaotic affair, perhaps the poorer Romans had a more communal experience of it. After all they may not have had the space to host. It may have inflicted upon some the fatigue we have when trying to ensure that you see everyone during seasonal celebrations. I have some friends who need a PA over Christmas in here in the UK to ensure they see all their friends and relatives and cause no offence to anyone.

Within the realm of the private celebration we meet a fundamental of the Saturnalia which I mentioned earlier. That slaves were afforded some level of freedom. I say ‘level of freedom’ because it’s plausible that some slaves were still required to work. All that feasting and eating at the wealthy Roman’s party – well that wouldn’t have been possible without slaves, or some slaves doing the hard work.

It may have been that the freedom afforded to slaves depended on a number of things. If you had a villa outside Rome populated by them you might imagine all would be given time off. Cato the Elder in his work On Agriculture noted that the slaves on his villa were given 3.5 litres of wine each. This does come with the caveat that wine in both ancient Greece and Rome was mostly lower in alcoholic content than today and that would be before you mixed it with water. In any case I’m sure it did the trick.

Perhaps in smaller households it would have been easier for slaves to join in. However, in large households perhaps some slaves were given more time off than others. A sort of reward system with some allowed complere freedom and others a rota or something which managed the logistical challenges of having an entire workforce who you relied upon suddenly not working.

Freedom for slaves came not only in what they could do but what they could say, backchat or just honest opinions were encouraged but this was a double edged sword. We get a unique insight into this from Epicetus, a source from the late 1st century AD. He had once been a slave and commented how being too honest may not be a great idea when the master – slave relationship was reinstated.

This element, the idea of a slave free to talk honestly leant itself to a bit of an in joke which I mentioned earlier. This related to anyone speaking above their station, or being accused of doing so. If they did , was met with a reference to the Saturnalia. Take, for example, a freedman called Narcissus who was sent by Claudius to give instructions to some soldiers. Try as he might when he made to outline what needed to be done the soldiers shouted back at him ‘Io Saturnalia’. In Petronius’ Satyricon a slave speaks back and is asked whether it was December yet.

There have been arguments around this practice of giving slaves temporary freedom and allowing them to dine and mix with their masters. Did it act as a social valve, allowing tensions between slave and master to ease? Or was it a reward system as I referrred to earlier? In the episode I did on helots, a people the Spartans subjegated and who worked the fields for them, I spoke about a possible hierarchy of helots where some were afforded responsibility over other slaves. It certainly seems to have been the case that in a large household staffed by slaves there would be some who were in charge as it were, of others.

Perhaps, and this is obviously all speculation, the opportunities afforded to slaves were mapped onto this heirarchy which differed on how many slaves you had and what kind of attitude you had towards them

Slaves weren’t the only marginalised group in the festival. Both women and children must have been a part of what went on. Again, their involvement was likely aligned to social expectations. A respectible Roman wife may have had the meal with the slaves but then withdrew when things ramped up. You might imagine then a rich family hosting a party with wives and non-slave women taking to a separate part of the house though hopefully taking the good wine with them.

As for children, again, this may have sat with the various ways people celebrated, though there is a story which involves a 14 year old, the then Roman emperor, singing and a very bad outcome. The story comes to us from Tactitus and I quote:

““During the amusements of the Saturnalia the two young men had thrown dice for who should be king, and Nero had won. To the others he gave various orders causing no embarrassment. But he commanded Britannicus to get up and come into the middle and sing a song. Nero hoped for laughter at the boy’s expense, since Britannicus was not accustomed even to sober parties, much less to drunken ones. But Britannicus composedly sang a poem implying his displacement from his father’s home and throne. This aroused sympathy – and in the frank atmosphere of a nocturnal party it was unconcealed. Nero noticed the feeling against himself, and hated Britannicus all the more.”

This event dated to AD 55, and Nero was a young emperor, only 18 himself. Nero’s cruel behaviour may have been very plausible because Britannicus was technially a threat to him. I say technically because Britannicus may have had no designs on the top job, but he was the son of the previous emperor Claudius. As such he could be used as a pawn to challenge Nero and perhaps by treating him this way at the Saturnalia Nero was attempting to reduce his credibility.

Britannicus’ success was fleeting, he died in mysterious circumstances shortly after this event. Obviously a coincidence.

In this story you’d also heard referenc made to the ‘king’. That is a feature of the Saturnalia where a person may be chosen at random to be in charge and they could ask anyone to do what they wanted. Obviously how this manifested must have varied, for example there may have been a restricted pool of candidates. Or perhaps not, perhaps everyone had a chance including slaves. Lucian, a 2nd century AD writer commented on what a king might do and this included libelling yourself, dancing naked or carrying a flute girl three times round the house. Lucian correctly pointed out that a main benefit of being king was that it offered safety from being asked to do the sort of ridiculous things a king might ask you.

But it wasn’t all crazy antics, Aulus Gellius a 2nd century AD grammarian and writer gave an account of what he and some other Roman friends did over Saturnalia when living in Athens. They spent it playing a trivia game, albeit one which dealt with questions about history, correcting commonly misintepreted tenets of philosophy, the investigation of a rare word or, drum roll here, the obscure use of the tense of a verb. Well, each to their own.

Lucian mentiond knucklebones and this was a form of gaming, of chance as these were rolled as we might do dice. Chance was important, not only for the purposes of gaming, but because it also brought with it the notion of equality in that anyone, assuming you aren’t cheating in some way, had the same chance of rolling a number or such.

Augustus reportedly loved to play dice at the Saturnalia and in fact throughout the year, Suetonius who reported this also wrote that Rome’s first emperor would give mischevious presents and gifts during the Saturnalia and this brings me to the whole shebang of giving and receiving gifts.

A primary source for Saturnalian gifts is Martial, a poet of the 1st century AD. Martial’s writings covered a wide range of topics and were often, shall we say, colourful. His epigrams contained around 223 gifts ideas running from the types of things you might expect through to the somewhat bizarre. I went through this list and tried to group them into broad categories.

I’ll start with what might be called tableware. There were common or basic cups, but then there were jewelled and crystal one, even a golden cup was listed. Dishes sat on the same spectrum, basic ones through to those inlaid with gold. What’s notable even within this small sample was the extra information provided by Martial in respect of where the objects might come from. The Cumean plate, which was made of earth from Cumae, Saguntine cups which suggest that they came from Saguntum in Spain or of that design. Even Etruscan vases were mentioned.

Moving from the table to it – by that I mean furniture. There were tables made of maple wood, citron wood and even inlaid with tortoiseshell. Next to them you might wish to recline on a couch which must have been another showpiece gift.

Sometimes it wasn’t just the expense of the items which indicated their status, rather what they might be used for. Snow was an expensive item which was sometimes used to chill wine, more likely during the summer months. A snow bag, snow decanter and snow strainer must have been welcomed when the summer came round.

Staying with the more expensive how about pictures? We don’t think of these as options but those of Hyacinthus and Danae were included. Artwork was an option, from a small silver statuette of Minerva to a terracotta Hercules. If you wanted a real talking point what about a terracotte mask of a red haired German. As Martial commented, this was also good for scaring children.

If you wanted a nice rest then pillows would help though perhaps even more so mattress stuffing made from woolen strands. A cheaper option was also given with the nickname of ‘circus stuffing’. It was made of reeds and as Martial noted ‘for the poor man’.

Possibly my favourite item from this category, which may easily sit in the next one, was a backstratcher in the form of a hand. I’m sure you can buy those these days? This item could easily belong in what I’ve termed health and appearance. We have balms, a medicine chest, and barber set but also hair dye and hair ointment. With the barber set we can confidently assume that this was for a man, but the hair dye may have been for both men and women. The same can be said of the combs, tooth pick, ear pick – which sounds terrifying and tooth powder for those whiter than white teeth.

Items for women aren’t numerous though this comes with the caveat that a lot of the gifts seem to have been for the use of both men and women, all those cups for example. However a breastband for the mistress, corset and girdle were included in Martial’s list. And those are translations by the way. The notion of gifts for women does bring with it more questions – for example, aside from the breast band were these items given by women to women?

The gifts I’ve just mentioned carry us into the category of clothing. There were many options and I suspect that these wouldn’t have been cheap.

Starting at the top we have a hat, a golden hair pin and hoods. The Gallic Hood came from the Santoni tribe, a Gallic people from the western central region of Gaul and this had a wonderful detail to it I’ll come to shortly. There were cloaks, leather and wool ones the former seemingly to be worn in the rain.

A toga must have been expensive but also ironic, the toga wasn’t worn at this time as mentioned earlier. What was worn, the sythesis, was on the list. Perhaps it was good to have a backup. Moving to the feet there were slippers but also socks made from the beard of a goat.

With goats I can segue into pets. Birds were popular, magpies, parrots and nightingales. But also dwarf mules and a small type of horse from northern Spain. Puppies and greyhounds also featured and of course a monkey. Now a few moments ago I mentioned a wonderful detail and this related to the Gallic hood which apparently resembled a smaller type of hood which monkeys sometimes wore.

For the avid reader, I’ve not got an obvious segue from small monkey attire as you can expect, there were works on parchments or similar. Cicero, Homer, Sallust, Livy and Ovid were all named as authors whose works you could give or receive. Moving into the caterogy of hobbies there was wool, in fact there were various types of wool, all sorts of colours and qualities of this.

Other hobbies might involve wool and there were various types, colours and qualities of this. For those who wanted something a bit more energetic dumbells, a discuss and different sized balls. Balls of various sizes might be encountered at the baths, no stop that, because it was a place where you’d often wrestle or play ball prior to using the facilities. Indeed strigils, for scraping the sweat from your skin, were another possible gift along with flasks to carry the oil. Not just any oil flasks, statement pieces such as flasks made of rhino horn. There were quite a few options then that could be used in the baths.

The final hobby related to gaming and dice, which as you’ve heard was very popular at this time. You could give someone dice or even a gaming table. Surely the TenBox of its day. On that distasteful joke I’ll head to food which covers both what you could eat and those who prepared it.

A sausage and even a pig with a priapus made of pastry. Let’s just say the latter was quite a moutful. In terms of who could help with this Martial refered to a cook and confectioner. Perhaps these were specialist slaves, though we meet the quandry I mentioned earlier regarding how a slave might do anything during this period. Perhaps then they were professionals well rewarded for working at this time of the year. Again, the idea that everyone in Rome was doing nothing but having a good time needed to be aligned with the practicalities of it all. Interestingly Martial also referred to a buffoon and comedians – after or even during the food you had entertainment covered.

As much fun as the Saturnalia was there were also the problems with giving gifts that we experience in the modern day. Take Martial’s complaint over a gift he received, and I quote:

“You have sent me as a present for the Saturnalia, Umber, everything which you have received during the past five days; twelve note-books of three tablets each, seven tooth-picks; together with which came a sponge, a table-cloth, a wine-cup, a half-bushel of beans, a basket of Picenian olives, and a black jar of Laletanian wine. There came also some small Syrian figs, some candied plums, and a heavy pot of figs from Libya. They were a present worth, I believe, scarcely thirty small coins altogether; and they were brought by eight tall Syrian slaves. How much more convenient would it have been for one slave to have brought me, as he might without trouble, five pounds’ weight of silver!”

Umber is guilty of that most cardinal of Christmas sins, regifting and Martial brings up the age old riposte of “couldn’t you have just given me the cash?”.

Elsewhere Martial raised other issues, what if you sent someone a gift and they didn’t send you one back? Also – what if you gave someone something and their gift was nowehere near the value of yours? Martial referred to the whole business and politics of gift giving as crafty and mischevious, concluding that gifts are like fish hooks. This was more a criticism within the context of the client / patron relationship at Rome where a wealth patron might have many less wealth clients. What do you send a rich patron exactly? Martial suggested you didn’t send anything at all.

Statius, the poet I mentioned earlier, had exactly this problem and bemoaned where he had sent a well bound book of his own works his patron had sent him a book of low quality speeches. Worse still the pages were mouldy. It’s possibly a bit tonge in cheek but Statius went on to list equally underwelming gifts his patron could have selected.

There was also something in ancient Rome which is certainly in play today. The deliberately naff gift. Upon receiving a book of poetry which Catullus described as both terrible and detestable he wrote how he may well send an equally awful set of poetry in return. This exchange was between himself and his strong friend Calvus, so we can be confident that this was deliberate. Proof that the art of a deliberately bad gift goes back a long time.

Finally, when it game to receiving gifts you might try to use the Saturnalia as cover for stuff you shouldn’t have been given. In AD 102 Julius Bassus was tried in the Senate for receiving gifts when he was a governor. He couldn’t deny these but instead tried to ague that all the stuff he received which he shouldn’t have were either birthday presents or ones given during the Saturnalia.

In case you wondered he was aquitted which sums up the nature of politics in ancient Rome quite nicely.

The Saturnalia was a complex festival and one which had changed over time but it retained a popularity thoughout Rome’s history. There’s even a reference to it in AD 448 where it was listed merely as a slave’s festival. The involvement of slaves and indeed how they were involved exactly is perhaps it’s most intriguing feature. As I have attempted to sketch out, though slaves were free it’s difficult to understand how this manifested exactly and in a sense it’s a fool’s errand because what I get from the Saturnalia was that it very much depended on the house or family who were celebrating it. Were you to travel back to Rome during the festival I suspect you’d find it being enjoyed in many different ways, from all in parties to those looking to locking themselves away and letting everyone else get on with it. Pliny in one of his letters states that’s exactly what he did, he had a room he’d go to during the Saturnalia and just let his slaves get on with it.

The festival turned much of Rome on its head, the subservise qualities manifesting at every level. Take for example the lack of official business, but also the celebrations occuring in the homes and streets. No longer where these the place of business, of traders moving goods and the regular activites of the day. Instead people wore different clothes, the acted differently and there was all that Io Saturnalia going on. Rome itself as a place had discarded formality and an entirely unique of social dynamics must have made it feel very unusual. All of this in the depths of midwinter and I wonder what effect this must have had on people, how it changed their mood? How the slaves must have felt and reacted to this temporary stay of servitude.

Though it was formed of experiences and elements which seem oh so far from us there are many ways in which it does relate. Working out who you needed to invite, whether to host or who to visit. I daresay you’ve either had those or heard those discussions. Of course there’s also the issue of presents, many of the ones which Martial described are similar if not the same as today. But some are very much not. Overarching this is the whole difficulty of knowing what to get and the wider politics of presents.

I’m now going to wrap things up, surely you can excuse me one last pun, I hope you enjoyed the episode. If you get the chance to leave a review or rate please do, but more importantly look after yourself and I mean that seriously. This time of year can be tough on everyone. Until next time keep safe, stay well and Io Saturnalia!