Thanks for listening and feel free to check out the other Halloween episodes I have done over the years.

Images.

I recently did a piece on the cursed sarcophagus of Ahiram in which I go into more detail.

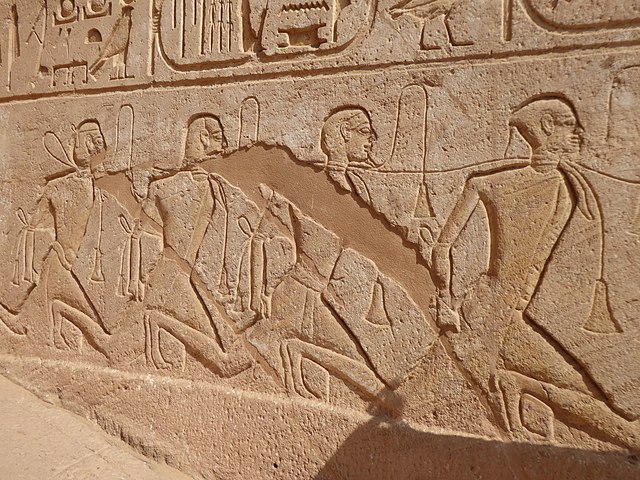

In the temple of Abu Simbel (13th cenury BC) in Egypt there is a relief showing prisoners taken by Ramses II. Below you can see them conforming to a familiar pose – kneeling with their hands behind their backs. You can also make out that they have been tied together at the neck, it also looks like their arms have been tied as well.

This is a lead figurine (Mnesimachus) in a lead coffin which dated to around 400 BC and found in the Kerameikos at Athens.

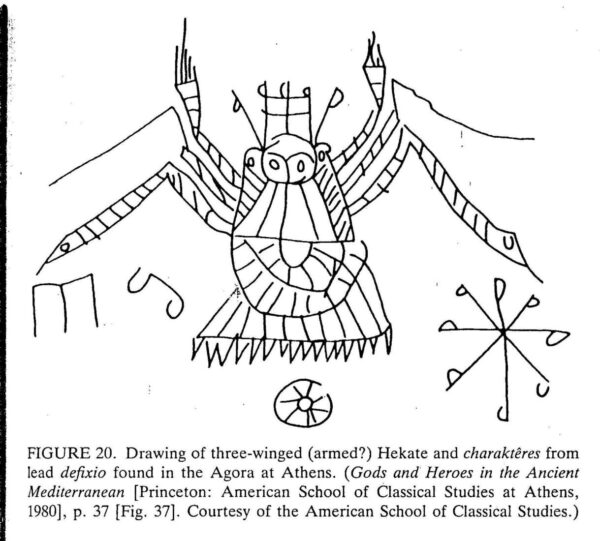

In the episode I mentioned the curious depiction of Hekate, here is a drawing of it.

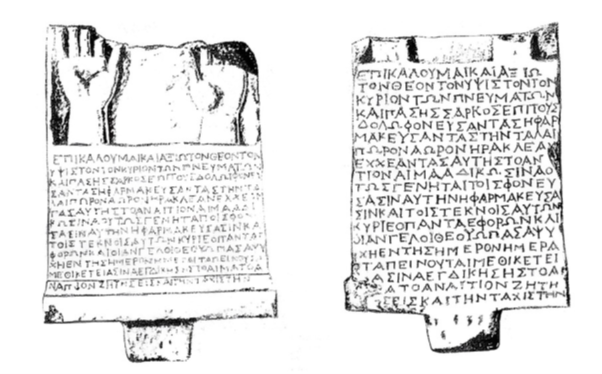

Below is the marble tablet found at Rheneia which has been argued as Jewish. The image can be found in Cursing beyond the grave: Imprecations and Jewish funerary culture in antiquity (see the reading list section).

The Egyptian Louvre Doll.

You might wonder why I didn’t include the famous Egyptian figurine exhibited in the Louvre (below). It’s known as the ‘Louvre Voodoo doll’ and it’s Egyptian dating to the 3rd or 4th century AD (there’s a good piece on it here with a translation of the spell). Whilst it looks very sinister, and in many ways is, it didn’t fit the criteria I set for the episode. This was about curses in the context of what would be considered a negative outcome (e.g. breaking up a relationship). The premise behind the figurine and the tablet which accompanied it is to bind one person to another in a romantic context. As I stated at the beginning of the episode I was focused on curses, that is where a negative outcome for a party is sought. This, even with the questionable morality of trying to make a person love you through a spell, is seeking a positive outcome. If I included this instance I would have needed to have included so much more material as well – in short I’ll be doing an episode in the future on incantations/spells which looked to unite, rather than separate.

Reading List.

Abusch, T. The witch’s messages, Witchcraft, omens and voodoo death in ancient Mesopotamia

Dickie, M. Magic and magicians in the Greco-Roman World.

Faraone, C. The agonistic context of early Greek Binding Spells in Magika Hiera.

Binding and burying the forces of evil: the defensive use of ‘voodoo dols in ancient Greece’

Gager, J. Curse tablets and binding spells from the ancient world.

Geller, MJ. The exorcists Manual.

Goedegebuure, P. Hittite Iconoclasm, in Iconoclasm and text destruction in the ancient near east and beyond.

Jordan, DR. New Greek Curse Tablets.

Kamal, SM & Shehata, HA. Curse rituals in Egypt.

Mouton, A. Hittite witchcraft.

Ogden, D. Binding Spells in Witchcraft and magic in Europe.

Saar, OP, Cursing beyond the grave: Imprecations and Jewish funerary culture in antiquity.

Schwemer, D. Witchcraft and War.

Magic rituals: conceptualization and performance in The Oxford handbook of cuneiform culture.

Strubbe, JHM. Cursed be that moves my bones in Magika Hiera.

Transcription.

Hi and welcome, my name’s Neil and it’s another Halloween and therefore another Night of the Livy Dead episode. I’ve been doing these Halloween specials since the podcast began so feel free to look through the back catalogue. I’ve covered werewolves, ghosts, demons, witches, exorcists and all sorts which featured in antiquity. As a bit of a horror fan, I always look forward to doing these. And in case you are wondering the reason for the delay in releasing the episode – this was due to covid. As an indie solo podcaster, it’s all on me, so anything like, say an illness which leaves me bedbound and unable to do much at all for several days, will have an effect on my schedule. But important thing is that you are here listening now to what I think is a really good episode.

In this Night of the Livy Dead I’ll be exploring curse tablets and curse figurines in antiquity – following their early appearances in Egypt and Mesopotamia through to Greece and Rome. The important word here is curse, because there is a large amount of spells, incantations, rituals and so forth which are couched in what is often referred to as love magic. Aside from the whole debate about what constitutes magic, a discussion for another time, I should clarify that I won’t be covering the type of activity where a romantic outcome is desired. Perhaps I’ll cover it in a future episode. However, that doesn’t mean I won’t be covering intimate relationships – as you’ll hear curse tablets and figurines might be used to prevent or stop a romance in its tracks.

There will of course be episode notes and a reading list on ancientblogger.com. If you want to get in touch you can find me on twitter/Instagram/youtube and TikTok as ancientblogger and this podcast also has its own reddit – ancient history hound and its own twitter or X account @houndancient.

I’ve been getting some fab reviews and ratings – if you can spare a couple minutes to do this on your platform that helps so much in getting this podcast a bit more exposure. But of course, the bigger thank you is to you for taking the time to listen.

Right then – let’s get to it.

I’m going to begin in an unusual place both in terms of time and location. It’s the 3rd century AD and long-time listeners will be aware that anything much past the early second century AD gives me a nosebleed but here I am in the 3rd century AD. I’m also in a well. Well, a well in the Athenian agora, again, not a place I am accustomed to.

It was here that a tablet was found with an inscription looking to bind a man called Eutuchianos. More specifically a wrestler called Eutuchianos. The inscription requested him to become weak and chill his resolve. Presumably this was from a rival, perhaps his next opponent. Sadly, we don’t know the outcome of the fight so we don’t know if it worked.

Curses, whether inscribed or in the form of an object representing a person was an old tradition by the time Eutuchianos was oiling himself and preparing to grapple. What I find interesting is how there were various manifestations of these across the different people and times and how these changed or sometimes didn’t.

I’ll begin with cursed figurine or cursed images in Ancient Egypt. The earliest surviving examples date as far back as the 6th Dynasty which was around 2,300 BC. At places such as Giza numbers of figurines were found and these early examples, moving through the following centuries took the form of either figurines or flattened out figurines, sometimes referred to as looking like gingerbread men. In the case of the figurines a common style was for the it to have its hands bound behind its back and this becomes a notable motif which we’ll see elsewhere. The kneeling and submissive posture belonged to a standard depiction of the defeated and those submitting to the Pharoah – it featured on reliefs for example and became a standard way of establishing the ruling Pharoah’s power.

Both types also featured inscriptions. It wasn’t so easy to do this on figurines, but we find names of specific people and even nations on them. Figurines dated to the rule of Pepi II who reigned in the 23rd century BC listed names of Egyptians, Nubians and other individuals identified as chiefs or commanders. The intention, as you have probably guessed, was to subdue and place a restrictive effect on these individuals.

By the Middle Kingdom Period, that is around 2000 BC to 1650 BC there had been a standardised script employed against anyone who might rebel against Egypt and upon figurines the names of all types of people and any rebellious activity were listed. These types of scripts have been understood as a more defensive type of curse, almost a pre-emptive one. The idea of the bound individual intended to restrain any potential rebellions.

A Pharaoh had this ritual to help ensure the stability of his rule, but this could presumably be the within the remit of the individual. The Coffin Texts date to 2100 BC and one spell involves making a wax image of your enemy and inscribing their name on it using the bone of a fish. So far I’ve set the context of these being used by the state against potential enemies or at least for the Egyptians against their enemies on a personal level. But what if was used by an individual against the Pharoah himself?

in 1155 BC we know that it happened.

Rameses III ruled from 1186 BC through to 1155 BC and he met his end through an event known as the Harem Conspiracy. This event was an assassination attempt which involved several key figures including a wife called Tiye who wanted her son as next in line. Though this was successful, it seems Ramses III died as a result, the conspirators were brought to justice and punished. All of this was recorded in a papyrus known as the Judicial Turin papyrus which featured those involved, and there were plenty of them. Many of these seem to have been senior officials.

The Lee and Rollin papyri included the names of two individuals who had both used wax figurines in the plot. These represented both gods and people. As with earlier the intent was to restrict them – presumably in their ability to protect the Pharaoh and against those who might discover the plot.

It wasn’t just Egypt which had an early relationship with curse objects and inscriptions. To the north the Hittites, a people based in what is modern day Turkey and Syria also used them. It’s fair to say that they took any instance of creating an image and naming it for curse purposes very seriously. The Hittite Laws, dated to between 1650-1500 BC stated that if you were caught then doing this you faced being brought to the king himself for judgment. The most important court in the land, somewhere you definitely didn’t want to be.

Curse objects and inscriptions weren’t entirely ruled out though and we find official examples of them. A good example of this is a tablet dating to the 18th century BC, here the curse was about anyone not agreeing to what was in the inscription. If you did contest it then you’d be automatically an enemy of the storm god. As a rule being the enemy of any god isn’t great but especially a storm one. We find a more explicit version of this type of wording on a decree issued by the Hittite King Tudhaliya IV who ruled in the latter half of the 13th century. The decree ended with, and I quote:

“This tablet must be placed before the storm god of Hatti, and no one may take it away from before him. But anyone who takes this tablet away from before the Storm god of Hatti or melts it down or removes the name or carries it forth may the Storm god if Hatti, the Sun goddess of Arinna and all the gods completely destroy him together with his offspring”.

These were terms and conditions you really, really didn’t want to violate. A similar warning was found inscribed on a sarcophagus found in modern day Lebanon. A landslide revealed a network of nine tombs, the oldest of which dated to the early 2nd millenium BC, but it was in tomb V where a sarcophagus was found with a curse inscription protecting the person who rested within it. The sarcophagus was likely reused, it dated to the 13th century BC. The inscription has been dated at around 1,000 BC and warned that any successor, King or governor would face revolt and a loss of power if they disturbed it. This even extended to damaging the inscription itself. And on the inscription, it was made in Old Phoenician and is the earliest example of that script which we have. I did a piece on this sarcophagus on ancientblogger.com if you fancy learning more about it all.

It might not be Kings targeting their rivals or successors. Curse wording could be used by a King as an insurance that his word was good. An inscription dating to the 8th century BC recorded a treaty involving King Matti’el, the King of Arpad a city in the north of modern-day Syria. The oath recorded on the stele indicates that it involved rituals, for example, at one point it read

“as this bow and these arrows are broken, thus Inurta and Hadad shall break the bow of Matti’el and his nobles”. You might imagine arrows being broken as this part of the oath was made. Likewise when the inscription reads: “As a man of wax is blinded, thus Matti’el shall be blinded”.

You can imagine a wax figurine of the king being blinded in some way as further ensuring the pact made and in sight, no pun intended, of the gods.

The use of figurines or, especially wax ones, will be familiar to those who listened to a previous Night of the Livy dead episode on Witches in Mesopotamia. A series of rituals, known as the Maqlu rituals involved spells to counter a witch and this involved making wax figurines of the witch and then melting them. The intended effect was to send the magic back to the witch, in short this intended to kill the person who had sent the spell.

The Namburbi texts, also Mesopotamian, date a bit later – perhaps as early as the 8th century BC. A ritual listed intended to protect a person from evil spells sent by a man or woman. This involved making a figurine or image of a man and a woman in clay, dough, wax and tallow and then writing their names on the left hip. Once done the images aren’t melted or burned, instead the hands are turned backwards, and the feet are bound. Here we meet that recurring motif, to bind the individual and restrain them. Presumably this wasn’t to kill the spellcaster, just to ensure that their magic didn’t work.

The use of magic, again, using air quotes continued to be a popular thing in this region. In the early Ptolemaic period (around the 2nd century BC) there was a daily ritual at Karnak in Egypt in which red wax images of Apophis, a deity associated with darkness and disorder, was bound back-to-back with effigies of the Pharaohs human enemies and destroyed. We can stay in Egypt for possibly the most famous group of texts – the Greek Magical Papyri. As you can probably tell these were a collection of spells, rituals, formulas and all sorts written on Papyri. They were produced from the 2nd century to the 5th century AD. But I need to turn west and to the Greeks who certainly made use of both curse texts and curse figurines.

Curse tablets, known as defixiones, and curse figurines or kolossoi, were more common than you might think in ancient Greece, but there was also a development which unwrapped a key element I’ve already mentioned – the concept of binding or restricting an individual. We’ve seen this in the literal form of some of the curse figurine, their hands behind them or otherwise in a submissive posture. In ancient Greece we have more of an insight into the concept of binding or restriction. Take the war god Ares – Homer recounted an instance of him being bound in the Iliad. Here the restriction is physical but consider the actions of the people of the port town of Syedra. Plagued by pirates in the 1st century BC they were told by an oracle to set up a statue of Ares who was bound in chains, the idea being that it would stifle the violence they were experiencing. If you want to know more about pirates in ancient Greece feel free to my episode that I did on it.

We can move from the serious in the Iliad to the almost comic. Ares is ensnared along with his lover Aphrodite in a bed, courtesy of a trap designed by Aphrodite’s’ husband Hephaestus. It’s one of the more amusing stories told in the Iliad. But was really your only option with a god, restricting them was as much as you could do. In ancient Greece curse tablets often took the form of simple small lead sheets and there were also curse figurines.

Plato noted in his Laws where commented on how they might be found at crossroads or doorways. There was a stern warning in a decree found at Cyrene which dates to the 4th century BC but supposedly harked back to the foundation of the Greek colony in 620 BC. An oath is mentioned alongside the melting of wax figurine, anyone disobeying the oath will melt like it.

This tradition, of pre-emptive warning curses can take a much more informal setting. Upon an aryballos, dated to the 7th century BC was written a sharp warning. It read “the one who will steal me will become blind”. The aryballos, a vessel used for perfume or oil and therefore a very personal object, not a state decrees. The aryballos was found at Cumae in southern Italy and gives a wider example, both geographically and context of how you could employ a curse.

Early curse tablets were simple, they contained the name of the individual in the accusative form and often they were linked to an area of everyday life you might not expect, the lawcourts. A good example of this comes from the Greek city of Selinus on Sicily. It dates to the early 5th century BC. On the thin sheet of lead was inscribed a request to bind the tongues of four named individuals, including the advocates of two of them. The inclusion of ‘advocates’ provided the context that this was a legal case. The presumption is that the person who wrote, or had this written, was trying to restrict the ability of those in court who were bringing a case against them.

As you would expect these have also been found in Athens, this was, after all a city famed in antiquity for its litigation and love of the courts.

There are references to the binding or restrictive power being used in a court setting in two very different Athenian plays. The first is the Eumenides by Aeschylus, part of the Oresteia trilogy. Here the Eumenides, otherwise known as the furies, begin a binding spell against Orestes who is effectively on trial. The second reference couldn’t be much more of a contrast. The comic-poet Aristophanes wrote the Wasps, a play lampooning old men who loved sitting as jurors. In one farcical moment a mock court is held which involves a dog as a witness. The dog’s silence on the stand is likened to an occasion when Thucydides, not the historian, had a frozen jaw in court. Though a curse tablet isn’t mentioned it plausible that this referenced this, you’ll hear later of an incident where a binding spell was certainly cited.

It might not just be the ability to speak in court which was intended. A tablet from Athens dating to the early 4th century BC was very comprehensive. It starts with the request:

I bind down Athenodoros before Hermes Eriounios and before Persephone and before Lethe, both his mind and tongue and soul and the deeds which he is plotting against us, and the dikē of Athenodoros which he brings to court against us.’

It continues in a formulaic way, repeating the same request for an individual called Smindyrides. It then moves to, Eirene, and not stopping there it extends to all the other witnesses and their supporters. Not only was this an extensive curse it also involved the reference to Lethe. Hesiod named Lethe as the goddess of forgetfulness, there was also a river in the Greek Underworld called Lethe from which the dead drank and forget their previous lives. It wasn’t just the tongues of those referred to in the curse which was being restricted or prevented from acting. Their memory of the events was also being targeted.

Two other examples relating to the world of the court are worth a mention. The first is a complex arrangement. It consisted of both a small figurine and a tablet. It was found in the Kerameikos in Athens and dated to around 400 BC. The figurine was made of lead and only 6cm long, its hands tied behind its back. On the right leg the name of Mnesimachus had been inscribed. This was contained in a miniature lead sarcophagus made of two sheets and it’s on this which had a number of names inscribed. The context is made clear by the wording at the end of the list of names. It reads ‘and if there is anyone else with them as an advocate or witness’.

This is obviously a bit more sophisticated and though no supernatural entities are mentioned does bring up the concept of the dead being used in curses and our final legal example involves just that. An undated find from Greece provided two tablets measuring 7 cm by 3cm. The inscription reads:

“Just as you Pasianax, lie here idle, so also let Neophanes be idle”.

The tablet accompanying it requested that Alkestor didn’t lay a lawsuit against Eratophanes. These tablets were presumably deposited in the grave of Pasianax. The curse aimed to project the idleness of the corpse onto Neophanes in order to prevent a lawsuit being brought against Alkestor.

The next context of curses is businesses and the world of commerce. It’s Hesiod who made the observation in his Works and Days that: Potter hates potter, builder builder, and beggar bears his fellow-beggar spite. Likewise, all singers. An epigram attributed to Homer mentioned a series of supernatural entities being called upon to smash the works of a potter if he made false promises.

Several curse tablets saw business rivals seeking to disable the other. A tablet dated to the 3rd century BC looked to bind Kittos, a slave who made nets. Another net maker Euphrosune was named as well as her workplace. A 2nd century BC tablet had Dionusios, a helmet worker and his wife, a goldworker called Artemis named as well as their products in the curse. Income is even specified as something to be bound by a 4th century tablet which also cites Hermes as the appealed deity. This would make sense as Hermes was a deity associated with trade.

Other trades might be targeted. Unsurprisingly a pimp is named along with a list of women’s names, presumably the prostitutes who worked for him. Another very old trade, tavern owner, possibly with sex workers, is also common. A 4th century BC tablet of some size, 41cm x 41 cm, requested Kallias to be bound, he was a shop or tavern keeper who was the neighbour of the person making the curse. Presumably this person did not get on with his other neighbour, Kittos, who made wooden frames. He was listed along with Philon, Agathon, Anthemion, Aristandos and someone referred to as the bald man – all tavern owners. Interestingly it also named Mania, another tavern owner – and I say interesting because this was the name of a woman. There were others as well I should say. All of these were required to have their soul, hands, tongue, feet and minds bound. This person must have been the neighbour we all dread.

Curse tablets offered a wonderful insight into how people were thinking about other people, and this could include affairs of the heart. Using spells, potions and rituals to capture the heart of another was a common thing. However, as we aren’t doing love spells we can look at anti-love spells and curses.

A tablet dating to the 4th century BC requested that Persephone help in preventing Theodora from getting involved with Kallias or Charias, requesting that Theodora remain unmarried. The tablet was inscribed on both sides and must have been deposited in a grave because the other side appealed to Hermes of the Underworld. It was also linked to the inhabitant of the grave – it reads ‘And just as] this corpse lies useless, [so] may all the words and deeds of Theodora be useless with regard to Charias and to the other people’. The tablet continued requesting that Charias not get intimate with Theodora and forget her.

Much like the other curses these intended to prevent intimacy or love from developing between people and we might wonder why that was. A scorned rival perhaps? Another 4th century BC tablet looked to bind Aristokudes and the women who will be seen with him. May he not marry and other woman or young maiden. Perhaps this was from his wife or an interested party?

At Nemea, 12km southwest of Corinth and in a pit a tablet was found which may be from one man to another. It names several body parts of the other man, including genitals, one reading is that this man didn’t want anything more to do with the intended. Genitals were also mentioned in a very different context in an undated tablet from Attica. It included names written clearly and written in a deliberately wayward fashion. This is seen elsewhere where names are sometimes written backwards, and the argument is that this helped make the curse more effective. In any case the genitalia of both a man and woman are listed as well as another couple. One reading here is that the genitals stop working – to bind them. Though that might sound amusing, it might just stop that level of intimacy there might be something else going on here. This might be an appeal to restrict fertility.

Sometimes the curse text didn’t include a name because it wasn’t known. This perhaps because of an unsolved crime. One such text belongs on a marble tablet which wasn’t placed in a private or hidden space but out in the open. It was found on Rheneia, a small island near Delos and on it the curse is as much an appeal for vengeance. A woman called Heraklea had been poisoned or had a spell cast against her and died. The appeal though isn’t with the standard deities. The ‘highest God’ is appealed to, the Lord who oversees all things. The inscription has been argued as having clear allusions to passages from the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible and what’s been argued is that this person was Jewish. It’s also noted that there was a Samaritan population at Delos, so it could also have been them.

It’s from nearby Delos that we have a lead tablet dating to the 1st century BC or AD, it’s not entirely clear. Here the request is to punish the person who stole a necklace. The script is Greek but argued as not being written by a native Greek speaker and it invokes Syrian, not Greek, deities to avenge the theft.

At this point I will turn to Rome, but I should add the caveat that cultures and people overlapped far more than we sometimes realise. Though empires waxed and waned, the Hittites were a long-lost thing by this point, there was much more of an overlap between them than we sometimes think. Greece and Egypt were very much still a thing by the time Rome took prominence. Their respective cultures hadn’t ceased to be – remember that ritual performed daily at Karnak with the wax figurine and the later Greek Magical Papyri.

The Roman Republic had a strong experience with what might be considered magic, as mentioned a difficult definition but a pragmatic one to use here. Romans did imagine that spells, divination, potions and all sorts of supernatural skillsets were around them. Lead curse tablets have been discovered around the Italian peninsula such as those in Etruria, Campania and Bruttium. These don’t seem to have been Roman as such, in fact those from Campania were written in Oscan and date to the 4th or 3rd centuries BC. These predated Rome’s rise but importantly this doesn’t mean Rome wasn’t exposed to them. You might be surprised as to how Rome absorbed the practices and trends from its neighbours, that is before it conquered them. I’ve mentioned these in other episodes that I have done, for example the incorporation of Greek religious practices in say the Saturnalia.

We might consider Rome having a love/hate relationship with spells and what we might later term as magic. In 81 BC a law was brought in at Rome, the Lex Cornelius de sicariis et veneficis. Those who perform bewitching or binding spells were to be crucified or thrown to the beasts. Magicians in Rome like other demographics, were a people who were occasionally exiled en masse from Rome.

Cicero, writing in the mid-1st century BC noted in his work Brutus that the orator Curio had forgotten his words in the middle of a speech and blamed this on spells used against him. Whether this was an excuse or whether Curio believed it is irrelevant as it was presumably a go to option, and we might recognise a reference to those Athenian legal tongue binding spells in play.

The suggestion of a curse with familiar elements is contained in a slightly more famous Roman work – the Aeneid. After the Carthaginian Queen Dido is told by Aeneas that he no longer wants to be with her the poem contains references to a witch and love magic. A pseudo ritual is hinted at with Dido collecting objects owned by Aeneas and forming a mock figure of him which is placed on the pyre. Once done Dido appealed to Hekate and shortly after kills herself upon it.

As mentioned these are familiar elements and perhaps perversion is at play here with Dido employing death as a mock image of Aeneas. One interpretation of this is that here was a form of the curse doll, but rather than employing a wax doll Dido herself is what is destroyed, and it is her spirit, through this ritual which will avenge Aeneas who is represented alongside her on the pyre.

Where we find a more direct reference to figurine being used for nefarious purposes is within the works of the poet Horace. His Satires, dating to around 35 BC included the famous witch Canidia. She was described as using figurine made of wax and wool – curiously the woollen one was used to torment and crush the wax doll.

The use of curse tablets existed both in real life and in later accounts of the historians. A curse tablet dating to the latter 1st century BC, perhaps around the time Horace was writing, placed a wholehearted curse on a woman, by a woman. This was found at Carmona, modern day Seville. The tablet requested that the gods of the underworld should cause the head, heart, mind, health life and limbs of a woman called Luxia to be affected by illness.

Moving into the 1st century AD there’s a quite extraordinary inscription from Tuder, modern day Todi in central Italy. It celebrated the actions of an individual who helped punish a slave who was tormenting the town senators through the use of curse tablets in tombs. As you may have already realised the use of curses wasn’t restricted to the rich. Analysis of the earlier Greek tablets revealed that those of lower status, perhaps those who could barely write, were issuing them. Sometimes the earlier tablets had wording which suggested that these were being done by a professionals using some form of a template. However, the most basic form of curse tablets or figurine were an option for anyone in any level of society. And that included famous names of the imperial period and even an emperor.

Germanicus was a famous general, and brother of the later emperor Claudius. His rise seems to have been a concern to the emperor at the time, Tiberius and after some success he was sent to Syria. It was here that he met his end. Some say he was poisoned on the orders of Tiberius, but the accounts of Tacitus added that within his residence tablets were found hidden away with Germanicus’ name and spells written on them.

Tiberius himself had some experience of names and spells written down. Earlier, in AD 16 a conspiracy against him was discovered. The perpetrator of this was an individual called Libo, and it was alleged that he had the names of Tiberius and others written down on parchment with what Tacitus described as marks of dreadful or mysterious significance. The only was to confirm Libo’s involvement here was to have his slaves testify that this was his handwriting, except slaves weren’t allowed to testify against their masters. Tiberius neatly sidestepped this by enacting a law allowing him to buy the slaves. We’ll never know if all this was true though because Libo took his life before they could testify.

Unusual marks or images on tablets aren’t something I have mentioned much but there is a quite remarkable design on one which was found in the Athenian agora and dated to the 1st century AD. It consists of script, symbols and a puzzling drawing. The text concerns the theft of some items from the little house in the quarter or street knowns and Acheloou. Hekate, Pluto, the fates and even the Erinyes are invoked to avenge this act. The drawing itself is hard to describe but looks something like a flattened crab with six legs and has been argued as representing Hekate with outstretched arms. Hekate was sometimes depicted as having three bodies, hence six arms.

I want to finish with tablets in perhaps a less expected format. Yes, I started with the tablet against the wrestler but there were equally curious and mildly amusing tablets dating to the later Roman empire.

Let’s start with possibly the most ambitious – it was found in Rome in a grave. Written in Greek text it dates to the late 3rd century AD. It was framed as a binding tablet and aimed its ire at Artemidoros, the physician of the 3rd Praetorian Cohort and also the entire land of Italy and the gates of Rome. Well, if you are going to go big, then go big.

In modern day Beirut we had a tablet from the 3rd century AD which not only targeted the horses of the blue team but also their charioteers. There are in fact a number of similar tablets found at Rome which also have this motif. Perhaps the most famous is the Sethian tablet which includes a Tolkein-length curse with a drawing of a horse headed figure holding a chariot wheel and a whip. The deities appealed to in this tablet were both Greek and Egyptian, possibly even Judeo-Christian angels. Near Carthage another tablet, again targeting a chariot team, this time the reds included a number of deities. It’s unclear who some are, but there’s a name with the comment ‘the god of Solomon’ and even Isos, which has been suggested as Jesus.

If we didn’t know how passionate people were about chariot racing and the heated rivalries we might pass this off as an outlier. However, that we do know how passionate things could get in the world of chariot racing means it would be odd if this sort of thing wasn’t going on.

I’m going to finish with a tablet which also dates to the later empire and, well, just made me laugh when I read it. We’ve all heard how showbusiness can be a very competitive affair, perhaps more so than anything involving a chariot, or at least as dangerous. On a tablet from Apheca in Syria and dated to the 3rd century AD an individual called Hyperechios, referred to repeatedly in the tablet as the bewigged pantomime of the blue team was singled out. The individual parts of his body are targeted in order from preventing a successful performance. This was pantomime on pantomime rivalry here. Actually, that’s not entirely unusual, there are some earlier Greek tablets dating to the 5th and 4th century which name performers and place a binding spell on them to fail. We know that, in Greece, dramatic performances could be in the context of a competition so perhaps it’s not all that surprising.

I hope you have enjoyed my attempt, in a short amount of time, to cover a wide range of peoples and centuries. In fact, this episode had probably been the one where I have included the widest date range, from ancient Egypt through to the later Roman empire. This was intentional as it feels that though there were different manifestations of the curse they were often couched in a similar context. And this links in with something I have always been passionate about in my podcast, finding the windows to what the average people were thinking and doing in antiquity. There are what feels like familiar motives here, ok perhaps less so when you are trying to bind an entire nation. But what we have are curse texts and figurines in the contexts of personal relationships, that is to say people preventing other people from getting on, falling in love, having a successful business or even a sports team from being successful.

Anyway, thanks for listening, I hope my voice held up ok, if you can leave a review or rating please do. Come say hi as well! Until next time, stay well and keep safe.