Gladiators are one of the most popular topics when talking about ancient Rome. However, there are some misconceptions about the gladiator which have stuck around and so here are a few with an explanation as to what’s not exaclty true about them.

Gladiators and the whole thumbs up or down thing.

I’ll start with the major one. Now, before I go further just consider the premise of this myth which posits that the fate of a gladiator was given through a thumbs down gesture from the Emperor. I’ve always found this one confusing based on what it implies, namely that there was a standardised accepted gesure. Was this gesture one which applied just in Rome, or across the empire? Presumably this gesture was also used by non-emperors as most of the gladiatorial events wouldn’t have had him in attendance. If not then who decided, the senior official or the person organising the event? It’s unclear and, more importantly, referenced fleetingly in our sources.

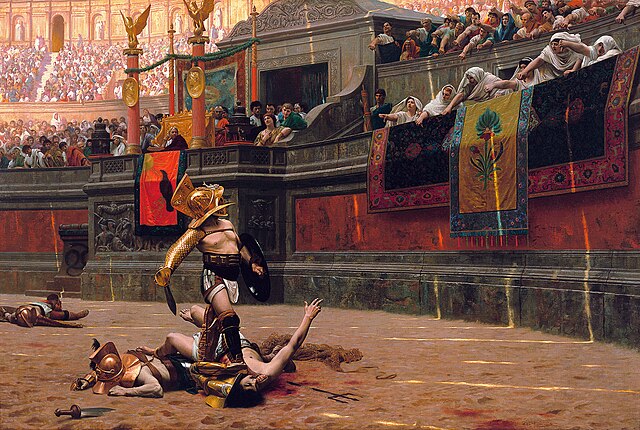

Much of the thumbs-down is influenced by the painting below.

The painting dates to 1872 and by the French painter Jean-Leon Gerome. The title of it is ‘Pollice Verso’ (Thumbs down) and this relates to the figures in white all gesturing with the thumbs down which dooms the defeated gladiator. This was a highly influential painting, but it’s not source material.

The actual reference to any gesture made in a gladiatorial fight comes from Juvenal who mentioned a turn of the thumb as indicating the gladiator should be killed. However, that’s it. In which direction was the thumb turned? Overarching all of this is the wider point that gladiatorial contetsts weren’t to-the-death as a default. Perhaps this option was only permitted on occasion when it had been agreed beforehand as if a gladiator died the organiser of the games would have to pay the trainer or owner of the gladiator. It could get very costly very quickly.

Like any good myth there is a kernel of truth within it – a gesture of some sort may have been used to indicate the fate of a defeated gladiator. What we don’t have is the context and what that gesture even looked like.

Gladiators as a sex symbol.

This myth is somewhat manifested by modern narratives, which I’ll come to shortly. But before that let’s consider the evidence of women in ancient Rome lusting after gladiators. To start with let’s review the source material left by women about their thoughts on gladiators. But, hang on, there isn’t really anything of that type. Purely on that fact alone we can’t know what Roman women thought of gladiators and even if we did have some source material it would need to be of a decent sample to get a generalised position.

Perhaps then we can consider a famous piece of graffiti at Pompeii which is often cited in this context. According to the scratchings Celadus was both the sigh of the girls and the glory of the girls. Presumably then Celadus, a gladiator, was popular with the ladies. However, this piece of graffiti was found inside the gladiator barracks. It’s as likely either written by Celadus or perhaps by someone mocking him.

At Pompeii there’s also the tale of a skeleton of a noblewoman found in the gladiator barracks and again the easy link made is that here were a couple of lovers caught, quite literally, in the act. However, the erruption of Vesuvius and the destruction visited upon Pompeii consisted of a series of events which lasted over 12 hours. The ash cloud plunged Pompeii into darkness and if you have listened to my episode on the sequence of events you’ll realise how traumatising these were. People were panicking and many found in collapsed buildings. It’s much more likely that this was a noblewoman seeking cover. The fact that in this small room several other skeletons were found further repudiates the lovers sneaking in a quick meeting. In fact a more horrific engagement could be implied.

But that isn’t to say that gladiators couldn’t have provided titilation (for both men and women by the way). In the entire duration of the gladiator shows at Rome and across the Empire the idea that at no point was there either an affair or something close between a Roman woman and a gladiator is almost statistically impossible. Gladiators were popular, Pliny the Elder reported that when a freedman of Nero put on a show at Antium paitings of the gladiators decorated the public porticoes. There were even scribblings on the tombs outside Pompeii which recorded the fight records of named gladiators. It’s entirely plausible that there were affairs had, but this seems borne more from a concerned male perspective than reality. As a kid growing up in the late 70s and early 80s the trope of the milkman or postman having affairs with married women was a popular one used to fund any number of skits. I’m sure it happened, but I don’t remember either job being marked out as one for would be Casanovas.

Possibly the most famous account of gladiators and Roman wives is found in Juvenal. In his sixth satire he records how Eppia, the wife of a senator, had fallen for a gladiator called Sergius. This may well have happened and in your mind a picture might be formed of a well built handsome man, the type which adorns the screen in any modern film or tv show involving a gladiator. However, according to Juvenal Sergius had a wounded arm and deformities on his face. There was a huge wart on his nose and one of his eyes continually leaked. That said what mitigated this was that Sergius was a gladiator. The point being that this status might cancel out the lack of an attractive disposition. As Juvenal concluded, ‘the sword is what they love’. Juvenal was rarely subtle.

The difficulty with Juvenal is that he is, well, Juvenal. He takes aim at all pockets of society and so we need to consider this in line with the bitter lens through which he scrutinised Rome. Of course it’s not impossible that women found gladiators attractive in a sense, but we need more evidence including evidence from women, to support this further. A main issue with gladiators was that they were considered the lowest of the low. In the modern narrative this works well as it forms an immediate trope of the taboo relationship which can work well with romantic themes. A love which breaks a societal norm has long been a popular story, Romeo and Juliet, Lady Chatterly and even Rose and Jack on a doomed ship.

This is where I think much of the motivation for this trope has come from. But it has also been reinforced through the films, particularly, the Pelplum films of the 60s in which bodybuilders started to star in sword and sandal films. These often featured bodybuilders and strongmen shoehorned into roles where they played famous roles from history in which they wore little and could flex. Hercules and Goliath were particularly popular (even Samson had a screen role). One famous bodybuilder, Reg Park even advised a young Arnie to go into film, his first outing ‘Hercules in New York’ wasn’t a great success but it’s safe to say that his career trajectory improved after it.

The tradition of gladiators with hewn-from-rock abs and physiques continues today. In reality gladiators lacked personal trainers (well ,that sort), nutritionists and make up artists. Though they were athletic they wouldn’t have sported the physiques which only modern nutrition (and perhaps the odd enhancement) would afford.

The final point I’ll make in this topic is the myth of gladiator sweat sold as an aphrodisiac. This is another myth which has stuck around because there is a small truth to it. The sweat of athletes mixed with the oil they used to cover their skin (glooios) was prized by the Greeks. One inscription at a Greek gymnasium even referred to the rights of any collected and sold from their premises. The jump from this to the idea that gladiator sweat was an aphrodisiac, however, is just not supported. In fact when I have seen this stated on social media I have on occasion plucked up the courage to ask for the source. The only response I ever received directed me to a blog which just stated this, with no source given.

Vegetarians.

Many years back I was invited by a friend to a sort of dinner party. Nothing fancy, but I can only describe it as that type of an event. As we were eating the host mentioned my love of ancient history and the person sat across from me started a conversation about gladiators. This included the ‘fact’ that all gladiators were vegetarians because they were called bean-eaters. This was a tricky situation to manage as this is partly true but the premise is wrong. I simply nodded and said ‘how interesting’.

It is true that gladiators were nicknamed after what they ate, Pliny the Elder called the gladiators ‘barley men’ (horderarii – see NH.18.46). However, the rationale for this wasn’t born from a moral position on the eating of meat. It was because barley was very cheap. Meat, on the other hand, was expensive. This moves to the point made earlier, that gladiators were largely expendable assets. Perhaps the more famous ones (and therefore the ones which the owner could charge more for) might have a nicer diet but as I understand it vegetarianism involves a choice not to eat meat. Gladiators rarely had a choice.

‘We who are about to die…’

A common theme in this article is how myths can sustain as they do due to a small element of truth which they hold. In AD 52 at the Fucine Lake near Rome the emperor Claudius held a battle (Suet.Claud.21). The fighters, before they began, turned to the emperor and shouted “they who are about to die salute you”, the imperial reply was “or not” and this caused chaos as the fighters interpreted this as a mass pardon. But this wasn’t a gladiatorial contest. This was a naumachia, a sea battle and the fighters weren’t gladiators. This moves to a wider point of what a gladiator was and wasn’t. Gladiators were trained to fight as gladiators, they commonly fought in pairs and in a specific manner (i.e. a gladiator type for example a murmillo). It can get confusing because there were other fights, though executions were more a mock battle, the condemned had little to no chance of survival. It’s plausible that gladiators were used in this setting but here they weren’t fighting in the context of the gladiatorial. A gladiatorial fight was one where one specific type of gladiator (e.g. secutor) fought another and there was a set of conditions. One of which seems to have been the presence of a referee to intervene if needed.

Just because you were holding a weapon at the games didn’t mean that a gladiatorial event was in play.

Podcast Episode.

You can listen to me talk about how the gladiator came to be in Rise of the Gladiator – on the Ancient History Hound podcast. Episode notes here.