I hope you enjoyed the episode, here is some extra bits which you may find useful. In the episode I mentioned my discussion with LJ Trafford about Domitian, here’s the episode. I also spoke about the date of Vesuvius, here’s the episode for that as well.

Pliny’s home.

As you can see from the photos Pliny grew up in a truly beautiful part of the world. It’s easy to understand how he found Rome cramped and preferred his villas for the countryside and gardens.

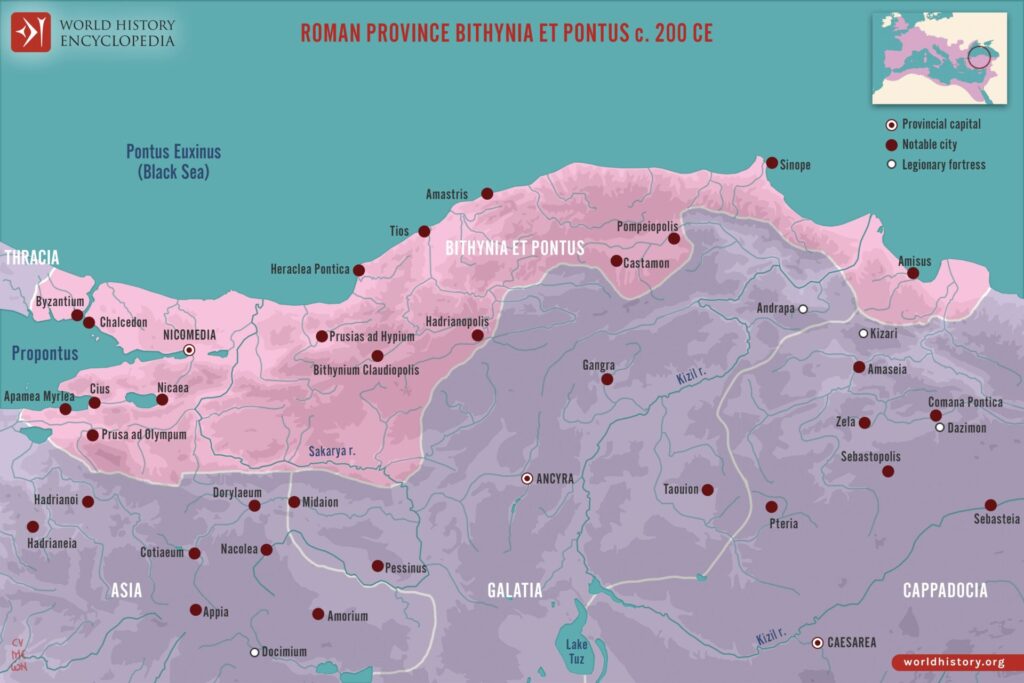

Bithynia and Pontus.

This province was an important and quite large one. You might recognise Pontus from a blog piece I did where the famous enemy of Rome, Mithridates, ordered a massacre in 88 BC.

Pliny’s date and the letters.

I gave a brief overview of this in the episode. The issue of Pliny’s letters and the dating of Vesuvius is covered in depth and very well in this blog piece. As for where his uncle was staying – the map below gives the location of Misenum and Stabiae.

Reading List.

There’s a great account on Livius about Pliny and if you want to listen to another podcast with the amazing Professor Catherine Edwards then check out the Pliny episode of In Our Time.

My copy of Pliny’s Letters is the Penguin version with an introduction by Betty Radice (very good).

Baraz, Y. Pliny’s Epistolary Dreams and the Ghost of Domitian.

Dunn, Daisy. In the Shadow of Vesuvius.

Johansson, BS. Damning Domitian: A historical study of three aspects of his reign.

Jonca M. Pliny the Younger and Christians.

Ohnler, M. Pliny and the expansion of Christianity in cities and rural areas of Pontus et Bithynia.

Stevens, S. Domitian: An Innovative Emperor?

Strunk, T. Domitian’s Lighting bolts and close shaves in Pliny.

Transcription.

Hi and welcome, my name’s Neil and in this episode or Plinysode, oh come on, you can give me that one, I will be talking about Pliny the Younger and his letters. Now, there are a lot of them, 368 in total so what I will be doing is focusing on some of the more famous letters – in particular, his account the eruption of Vesuvius which he witnessed, and what to do with a small but problematic religious sect called the Christians. I’ll also be giving an overview of his life and other letters which cover a range of topics.

Before I start the standard fare of pointing you in my direction. I’m on Bluesky, Tikok, X, Instagram and Youtube as ancient blogger. There’s also a subreddit for this podcast called AncientHistoryHound which is also my name on reddit. Finally, my website which will have episode notes which includes a transcript, supporting content and a list of sources I have used. One book gets a special mention – ‘In the Shadow of Vesuvius’ by Daisy Dunn. I bought this as part of my research and it’s a great read about Pliny the Younger and much more.

Thanks for those those reviews and ratings which have been coming in on Spotify – but don’t forget Apple podcasts if you listen on that platform and in fact on any platform. You may not know this, but these give my podcast more exposure and results it being suggested to more people. For an indie podcaster with no marketing budget it’s what I rely on.

Ok then, let’s begin.

Lake Como sits south of the Italian Alps and north of modern-day Milan. It’s a picturesque location and we may know it today as a place where many celebs and A-listers have stayed for those breathtaking views across the lake and hills. Keeping with the theme of celebrity it was a sort of celebrity who founded a colony on the southern shore of the lake in 59 BC, it was called Novum Comum and the celebrity of sorts who founded it was Julius Caesar.

In either AD 61 or 62 Gaius Caecilius Secundus was born, or as we more commonly know him, Pliny the Younger. His parents were wealthy and from the equestrian class, his father, Lucius Caecilius, died early in Pliny’s life leaving him to be brought up by his mother Plinia and a guardian, Verginius Rufus. Pliny seems to have felt a great deal for Rufus, he speaks of him very fondly in his letters. As a young boy Pliny had a private tutor and seems to have been a very capable student, writing a Greek tragedy at the age of 14.

Pliny wasn’t the only Pliny in Novum Comum or from it – Pliny the Elder was Plinia’s brother and thus Pliny the Younger’s uncle. He too played an important role in the life of the younger Pliny though in AD 70 this was put on pause as he was made a procurator and as such had to travel the empire. However, we know that the pair were spending time together in AD 79 because of the eruption of Vesuvius.

The two letters by Pliny, covering the eruption of Vesuvius are possibly the most famous of his letters. In these he described the actions of his uncle, the Elder Pliny, and his own experience of the event. What you may not know is why he came two write the letters in the first place. It wasn’t because of the eruption as such. Some 30 years after the event the historian Tacitus sent him a letter. The request was to find out how his uncle died as Tacitus was interested in this, presumably because Pliny the Elder was a famous person in his own right.

Pliny’s first letter outlined the events, how he and his uncle were staying at Misenum. This was in the northwestern part of the bay of Naples, and it was where his uncle was stationed as he was in charge of a Roman fleet there. His account begins with his mother pointing out a strange cloud rising from Vesuvius which Pliny described as like a pine tree. His uncle decided to investigate and as he was making ready he received a note from some friends asking for help in evacuating them. Pliny the Elder set sail across the bay and landed at Stabiae, near to Pompeii.

Despite the falling ash and fires in the distance Pliny the Elder disembarked and stayed with his friends. He dined, bathed and was sleeping when awakened by the increasing panic of those around him. The decision was made to leave but Pliny the Elder was overcome by the ash and fumes on the shore. His body was found two days later lying as if asleep.

Pliny obviously thought highly of his uncle, but his letter described him in almost a contradictory sense. On one hand he sped off on a mission of mercy but upon reaching his friends decided to take a more relaxed attitude which ultimately had a fatal outcome for him. Pliny’s second letter was in response to Tacitus wanting to know more about what happened and in this letter Pliny wrote of his own experience. How he was forced to leave Misenum due to the tremors, of the darkness and the falling ash. When he returned to his uncle’s house the skies had cleared he described a landscape covered in ash as if it was snow.

Pliny was only 17 or 18 at the time and his letter, as mentioned, was written to Tacitus decades later. But it included some details which weren’t fully appreciated until the modern period – the description of the pine tree cloud being one such example. It was testament to the accuracy of his account. With that said there is one aspect of his account of the eruption of Vesuvius which does need to be addressed, and this leads to a wider point I need to make about Pliny’s letters.

It’s in Pliny’s first letter to Tacitus that he provides the date of the 24th of August as when it all happened. You are probably aware of the debate on this and I have discussed this in my episode on Pompeii. However, I’m going to leave the arguments about archaeology and ash dispersal patterns to look at an important point which is sometimes missed.

The central issue is that we do not have any surviving original letters by Pliny. Instead, what we have are fragments and much later copies. The earliest set of copies we have date to the 5th century AD, and these weren’t discovered until around 1500. What we do have though are fragments and copies of copies, sometimes different copies made at different times of the same letter spread across the intervening centuries. An issue you’ve probably realised already is where we have differences in the copies. Pliny’s account of Vesuvius which gives that famous date is one example of this. In some copies of that letter the date is different, in others absent. This is why we have a date, but also don’t. If Schoedinger’s cat had a birthday it would be the 24th of August but also wouldn’t.

And just before I continue, it wasn’t until the early 14th century that it was realised that there were two Plinys and not just one. It’s a good example of how we can have an expectation that the knowledge we have today was consistently held from antiquity. In reality a lot was lost and then rediscovered later on.

Pliny the Elder left the younger Pliny everything in his inheritance and this included his name, hence Pliny the Younger. Given what he now had it might have been tempting to live a life of relative luxury, I know that’s what I would have chosen. But thankfully Pliny was made of more ambitious stuff. At the age of 18 he was in Rome and beginning a legal career in the Centumviral Court, or Court of 100 Men. This court dealt with wills, inheritance and fraud. Pliny’s rhetorical abilities shone, helped no doubt by the earlier tutoring he had received from Quintilian a famous teacher of rhetoric. Many of Pliny’s later letters pick up on the art of speaking, whether it be reviewing his own speeches, the speeches of others or attending speeches. Though he had a love of poetry and writing it seems he was a real nerd for the art of speaking.

The Centumviral Court was no doubt a tough and competitive arena. Pliny’s next role was as challenging but in a very different context.

The Gallic III legion had been formed under Julius Caesar and, as its name suggests, was recruited in the north of Italy. The Gallic III had moved to Syria under Mark Antony, and in AD 45 the emperor Claudius had settled some of its veterans in modern day Acre. The legion became strongly associated with the east and its soldiers adopted eastern customs. This was to have a fortuitous outcome in a battle during the year of the 4 emperors. At the Second Battle of Bedriacum in October of AD 69 the Gallic III fought alongside other legions which had backed Vespasian against the forces of Vitellius, the current emperor.

The battle had extended through the night but as the sun rose the Gallic III started cheering. This was a custom they had picked up from their time in the east. The Vitellian army thought that this was because reinforcements for Vespasian had been sighted and panicked. Their lines broke and they retreated. The cheering from the Gallic III had won the day.

When Pliny came to join the Gallic III, they were back in the East in modern day Syria. Here he was a military tribune responsible for the administration and specifically the financial side of things. In a later letter Pliny described going through the accounts to ensure that there was no fraud or discrepancies something which was more common than you might think.

Pliny’s next career was as step up in what’s often referred to as the Cursus Honorum. This can be loosely described as the political ladder, if you wanted to get to the top there were a series of rungs to climb. In AD 90, when he was still in his late 20s, Pliny became a Quaestor. This was as an elected magistrate whose main role involved conducting audits and overseeing the state treasury. It wasn’t just a move up the career ladder it was also a move up the social ladder because Pliny was entered into the senatorial class. The senatorial class required a property requirement and nominations – Pliny must have been held in high regard.

Pliny’s climbing of the social and political ladder had occurred under the emperor Domitian who ruled from AD 81 to AD 96. Under Domitian Pliny was made both prefect of the treasury and a tribune – again both important positions. And here we meet what can be best described as an awkward truth because Domitian came to be highly unpopular with the senate. After his assassination in AD 96 the senate condemned him.

Pliny wasn’t alone – both the historians Suetonius and Tacitus, who Pliny exchanged letters with, also had worked under Domitian. Both had nothing but bad words to say about him, In Suetonius’ work ‘The 12 Caesars’ he is depicted as the worst type of tyrant. We don’t have the section of Tacitus which covered his reign but in his work Agricola he gives a damning portrayal, noting that and I quote ‘even Nero withdrew his eyes from the cruelties he commanded’ end quote.

The question of whether Domitian was a tyrant has been a point of debate in more recent times. In fact, you can listen to the excellent Domitian fangirl herself LJ Trafford in an episode called AD 69 and daily life in ancient Rome where I challenged her to make a case for Domitian being a decent emperor and I have to admit it was a case well made.

Why then did the senate hate Domitian? What had he done to cause that reaction and now place Pliny, and others, in such an awkward position. The unpopularity was largely the result of some prosecutions of senators and their families as well as Domitian’s attitude towards the senate at the end of his reign. For Pliny, however, we can be a bit more specific, and it related to a culmination of events in AD 93.

It was then that Domitian had responded to what he saw as provocative moves by a faction within the senate – the stoics, otherwise known as the stoic opposition. They were named after the school of philosophy which they followed, and Pliny had become associated with a number of them. This wasn’t a new thing, under Vespasian, Domitian’s father, a famous stoic senator called Helvidius Priscus had been exiled and then executed. Priscus had now risen from the grave to become a thorn in the side of another Flavian emperor, Domitian and this took the form of a biography of his and another stoic which was published. The response was suitably brutal. It had been the widow of Priscus, named Fannia, who had organised this. She was exiled. The two authors of the biographies, both senators, were prosecuted and executed. Even the stepson of Fannia was executed for a farce he had written which Domitian took offence to.

When Pliny published his letters there were several which looked to clarify his role in all of this, and I mean his lack of a role. Perhaps he felt guilty of surviving? Perhaps he wanted to ensure that people didn’t question his loyalty to his friends – in a bad bit of timing he had been promoted to Praetor, a very senior position, in the same year as this was all going down. A worry Pliny had was that he might be viewed as somehow complicit.

Several of his letters sought to address this. There were ones where he had written about his support for Fannia whilst she was exiled and upon her return after the death of Domitian.

Another letter mentioned how he courted danger staying with Artemidorus, a philosopher who had been banned by Domitian. Pliny even wrote to Tacitus with an account of an important court case and asked if Tacitus might include it in his work. His partner in the legal case was one of the biographers executed by Domitian.

A final example was the inclusion in a letter where Pliny had found a document in the desk of Domitian after his assassination. It was from Carus who had accused and prosecuted one of the biographers and it denounced Pliny. The implication was that had Domitian lasted much longer Pliny would have been next on the list.

The letters give the impression of Pliny as a bystander who was unable to do much to save his friends. More importantly they underline how he didn’t benefit from this. He wasn’t about to throw his friends under the bus to improve his position. These letters dovetail with a criticism of Domitian made years later when he was consul under Trajan in a speech. In this he called Domitian the most treacherous of emperors and named himself as one who had lived back then in grief and fear.

For both Tacitus and Suetonius, the question is to what extent were their accounts of Domitian balanced. Were they formed purely out of a personal experience of him? Was there an element of survivor guilt? Their works were published long after Domitian was gone, and their treatment of Domitian had a unique dynamic to it. Both had done well under a supposedly tyrannical ruler. Perhaps it was useful to clarify their opinion of him for a number of reasons.

After Domitian there was the emperor Nerva who only reigned for a few years and following him it was Trajan. Under Trajan Pliny’s career soared to new heights. In AD 100 he became consul for a few months, he was only 38. It was a few years later, in AD 103, when Pliny began to publish the letters which formed the nine books published in his lifetime. We have 247 which have survived but as I mentioned not the originals. And even these weren’t the originals he’d written in the years previous. These were in fact the ones which had been redrafted, edited and given a bit of a rhetorical polish.

Pliny continued with his legal career, prosecuting two ex-governors for corruption. One was Julius Bassus who had overseen the province of Bithynia and Pontus. Trajan was keen to utilise Pliny, making him an augur and the curator of the Tiber. This involved overseeing the sewers in Rome and flood defences. It might not sound like much of a job, but both these aspects were of high importance. Rome had always suffered from floods and Pliny seems to have had a good ability with pairing the practical with the economic. Trajan would have known that anything done under him would have been stable in the physical sense and on the balance sheet.

Pliny’s career so far had evidenced his expertise as a financial troubleshooter and someone who could be relied on with large projects, including infrastructure. His next role was to incorporate these elements on a much larger scale than he had previously experienced.

The province of Bithynia and Pontus was a province formed from initially two separate regions which hug the northern coast of modern-day Turkey. This was a senatorial province, meaning the Senate would normally choose the governor but it seems Trajan leant heavily on Pliny being chosen and around 109 BC he arrived to fix what was a broken province which had been thoroughly mismanaged. Financial black holes and poor infrastructure were endemic, as such You can see why he was such a good choice.

Book 10 of his letters covered his time there and this book is sometimes held separately from books 1-9 for two main reasons. That they were published after his death and that they were exclusively about his time there and correspondence with one individual. The emperor Trajan.. Just pause there – this book has replies from a Roman emperor. One of these exchanges is famous, although at the time it was one of many issues Pliny had to field. Not a broken aqueduct but what to do with this bunch calling themselves Christians.

The Christians were just another problem for Pliny but not one he had encountered before. He wrote to Trajan informing him of his current approach. Anyone who still responded that they were a Christian after being questioned on this several times was sent to prison. The implication here is that this meant execution of some sort as Pliny mentioned how if any were also Roman citizens they’d be sent to Rome. Executing Roman citizens required special authorisation.

This left two groups to be dealt with. The first was those accused who denied ever having been a Christian. These were easily dealt with, after performing a sacrifice to the Roman gods and denouncing Christianity they were let go. This left the final group – those who were once Christians but weren’t anymore. It was this group that Pliny wanted clarification of what to do with.

Trajan’s reply was succinct. Keep doing what you are doing but don’t go actively hunting Christians. The emperor also added an important point – don’t go trusting or responding to any accusers or pamphlets. Pliny had mentioned in the letter that names of potential Christians had been suggested to him and also circulated on a pamphlet. This was almost a separate issue as the role of accusers or informers was often a dangerous thing as people will start accusing others for all sorts of reasons. Trajan knew that this could end up causing social disorder and so wanted to ensure that it wasn’t made a valid practice.

Aside from the angle of policy Pliny’s letter carried details about the Christians and what they got up to from his investigations. They would meet before daybreak, recite a hymn to Christ and then swear an oath ensuring they would not commit any crime and abstain from robbery, theft, adultery and a breach of faith. The Christians used to meet later in the day but had stopped because of an edict in the region prohibiting such types of meetings. Rome had long been concerned over societies and groups forming and being places where political dissent might form. In fact, Pliny wrote to Trajan requesting a fire brigade be set up in Nicomedia following some fires there. A sensible request you might think. But Trajan denied the request, stating that in the region there were factions, and I quote and that such associations might degenerate into secret societies, end quote. Pliny had anticipated this and even written how he’d oversee the brigade – but it was still too risky in the opinion of Trajan.

The Christians themselves don’t seem to have posed much of a threat or at least not one that rang any bells with Pliny. His main concern was the role of accusers and informers, he even blew his own trumpet by concluding that the actions taken had already seen people returning to the traditional forms of worship.

The letter has been viewed as a critique of Pliny, that it showed him unable to deal with a situation and confusingly asking for guidance whilst already undertaking actions.

Well, that’s one way to look at it. Another is that Pliny was playing a clever game. True, Pliny does ask for guidance for that specific group of ex-Christians but the letter can be read as more outlining his policy with a question to ensure a response. Pliny states in the letter that his preference with regards to the ex-Christians was to let them return to the traditional worship. Read this way it’s a clever tactic of having Trajan sign off on what he was doing. Why would he want to do this? Well, Pliny had been involved in the prosecution of ex-Governors. Perhaps he feared that anything he did in region may be scrutinised and as such he now had a letter from Trajan confirming that what he was doing was with Imperial knowledge and approval.

Pliny never faced any prosecutions because, sadly, it doesn’t seem as if he made it back to Rome. His death is given at around AD 113 and it was either in the province or on his way back.

Even though he was in his early 50s he’d had a truly remarkable career, and his letters help us understand this. But they do much, much more. The letters allow us to understand Pliny as well as they world he was living in. And as I come to the end of the episode I want to talk about what more the letters can tell us about him, what he loved, what he didn’t, who he hated and some random bits from some of the letters.

Let’s start with the loves. He loved literature, particularly speeches which seemed to be something he was very good at. Speechwriting and rhetoric was a hardy craft – you might spend several hours in court giving one so it was a very developed skill. In his letters he often discusses a visit to watch someone give a speech or talking about the speeches of others and his own. He spent time drafting and writing speeches in villas and two are described, similar in a way but also different. Pliny’s Tuscan villa was luxurious and he describes in detail the different trees, the gardens which included box-hedges clipped into shapes. He was also a keen gardener; in one letter he wrote how he enjoyed getting to know each fruit tree and vine. His Laurentine villa near Ostia was more austere and though the gardens aren’t described the surrounding woods, and the nearby sea are. And he delighted in both. The villas offered Pliny a space outside of Rome and somewhere which may have reminded him of his upbringing in Novum Comum.

Being more of a country boy than a city boy, Rome was more tolerated than anything else. Perhaps this coupled with the sort of work he undertook there led him to remark, and I quote

“the din, the futile bustle and useless occupations of the city” end quote. Aside from Pliny I wonder how many others who were born outside Rome and ended up there had similar thoughts.

His hometown, Novum Comum, featured in numerous letters. In one letter he states that he had gifted it 1.6 million sesterces. Much of this was to improve the educational facilities and this perhaps links back to his experience growing up. He’d been lucky enough to have a tutor and he mentions how he was inspired to help fund tutors there after hearing how one family had to send their son to nearby Mediolanum (Milan), some 40 km to the south for education.

In AD 96 or 97 he had a library built and donated 100k each year for its maintenance. He also spent a large amount to source teachers for the freeborn young, both boys and girls. His generosity wasn’t just to strangers, a childhood friend was loaned 300k so they could qualify for the rank of equestrian. He even bought what he hoped was a genuine antique Corinthian bronze sculpture which he wanted to have put in the temple of Jupiter. Sadly, it’s not been found so we don’t know if it ever made it there.

In his letters Pliny deals with a range of characters, in fact he wrote to over 100, but one receives more vitriol than everyone else put together. Allow me to introduce you to Marcus Aquilius Regulus.

Regulus had been an informer under Nero and even in the time of Pliny was associated with the dark arts of the legal profession, particularly involving wills where he’d attempt to manipulate the wealthy into leaving himself something. Of course, this was an area of specialisation for Pliny, so he well knew those dark arts and he must have hated Regulus even more. If this wasn’t enough Regulus was also involved in the prosecution of Fannia under Domitian.

Pliny’s gave an account of him, and I quote:

“He has weak lungs, he never looks you straight in the face, he stammers, he has no imaginative power, absolutely no memory, no quality at all, in short, except a wild, frantic genius, and yet, thanks to his effrontery, and even just to this frenzy of his, he has got people to regard him as an orator”

End quote.

Even when Regulus lost his son Pliny didn’t believe any of his mourning was genuine. And when Regulus himself met his end Pliny wrote in a letter about his memories of him and noted that (and I quote) Regulus did well to die and he would have done better still if he had died earlier (end quote). Savage.

If you think about Pliny’s letters as a series of photos you can consider what he’s showing us in the forefront, but there’s also a lot of detail in the background and that, for me is equally as important. It’s through his letters that we get descriptions of how things worked. Take patronage where several letters are Pliny recommending people for a variety of roles. There are the dry legal technicalities, the small cogs of the legal system revealed to us- how court hearings and how strategies were mapped to them. A sort of easier to understand Ikea instruction manual.

But there’s also the random stuff. A letter where Pliny fumes about how a host kept the good wine at a meal for those close to him and served the rest much cheaper fare. The annoyance at how people fidget at speech recitals. His love of nature and a mysterious pool which empties itself and refills. A famous tale involving a dolphin which saved a boy and allowed itself to be ridden. The dolphin became a tourist attraction and was then, let’s say, removed, when it got too popular. Pliny’s ghost story is one I have featured in my Halloween episode and where we get the trope of a spirit haunting a house whilst rattling its chains. These are just some and I’m sure moments after I stop recording I’ll be kicking myself for not mentioning others.

If you are looking to learn about Rome, particularly if you are studying it, I’d suggest you read a couple of letters a day. It’ll build up your background knowledge and though there are centuries between us and Pliny many of his letters have moments where something will resonate and for me that’s another layer of their beauty.

I hope you have enjoyed this brief overview of Pliny, if you get to read any of his letters let me know what you think of them. Until next time, take care and keep safe.