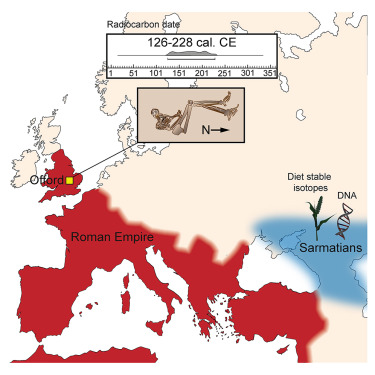

In 2017 work was being done outside of Cambridge in the UK. These were upgrades to the A14 road and though needed weren’t exactly headline grabbing. However what they found allowed experts to piece together a tale which linked Roman Britain to the easternmost tips of the Roman Empire. Whilst digging the remains of a young male were found (thought to be aged between 18-25). Experts from the Francis Crick Institute and MOLA Headland Infrastructure set about understanding more about this individual. You can read the full report here.

Heading back to Sarmatia.

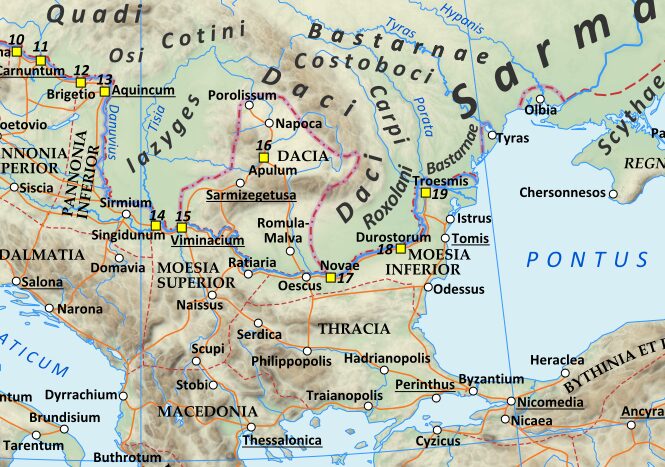

Initial work dated the remains of the man to between AD 126 and AD 228, in short Roman Britain. DNA, retrieved from the inner ear, revealed that the individual had maternal and paternal lineages which linked them to a region in modern day Armenia. The area in which modern day Armenia sits was once the lands of the Sarmatians – a nomadic people. The Sarmatians were formed of sub-groups, the land between the Caspian and Black Sea on of their haunts. That said these people weren’t restricted to that part of the world. By the time of Hadrian one tribe, the Roxolani, made it to the northern banks of the Danube in what is modern day Romania.

Rome and Sarmatia.

The gradual expansion westwards resulted in the Sarmatian tribes interacting with Rome and this escalated. In the latter half of the 2nd century AD Rome was at war with a number of tribes (the Marcommanic Wars). The main front for this war was the Danube, and though it involved Germanic tribes a Sarmatian tribes, were also involved.

It’s the Iazyges which we need to focus on here because in AD 175 Marcus Aurelius defeated them and part of the resulting treaty involved Rome receiving several thousand of their cavalry. Of these 5,500 were sent to Roman Britain.

Sarmatians out west.

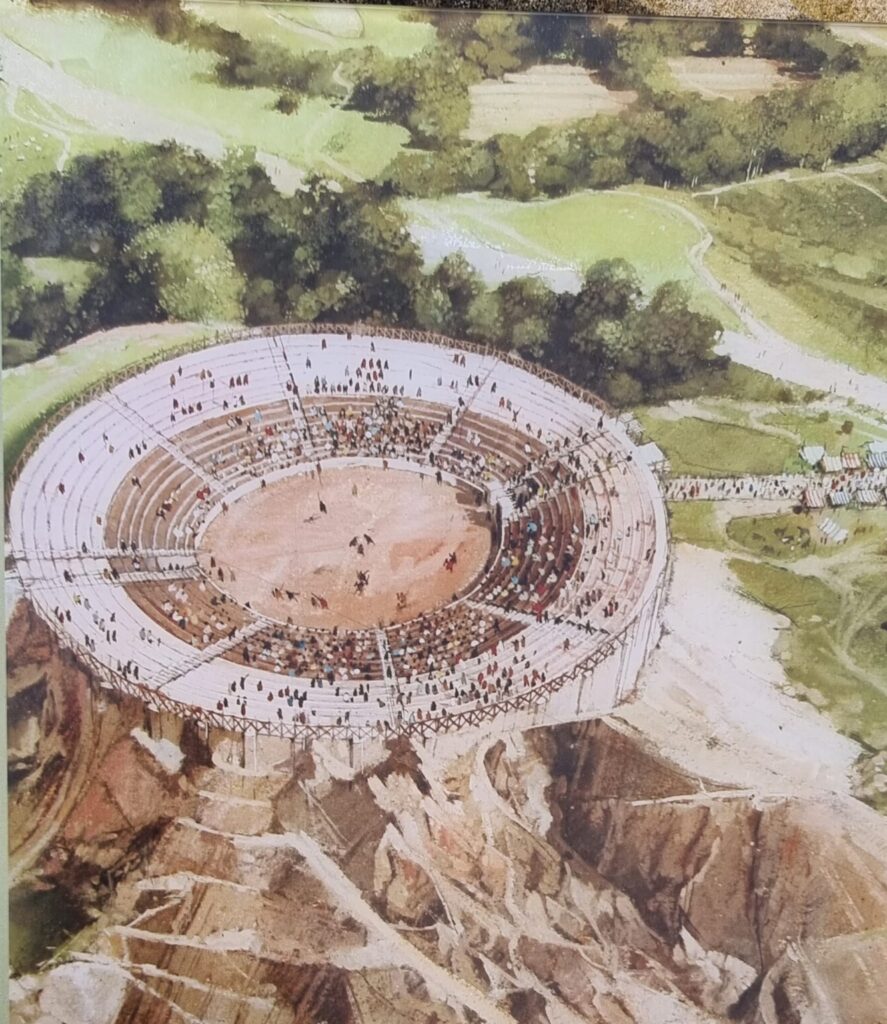

As typical cavalry units numbered 500 the number sent to Roman Britain represented 11 detachments. We know of some of their business, there is a tombstone of a Sarmatian cavalryman in Chester (also known as the Draconarius tombstone). In Ribchester a funerary inscription and a dedication to a temple references them. At Catterick tiles were found stamped with name of a Sarmatian cavalry unit. However, does this mean the individual found outside Cambridge was himself one of these soldiers? It’s unlikely and the evidence comes from isotopes found in his teeth.

Straight from the horses mouth.

The isotopes indicated that this individual had spent the first 5 years of his life in the same location. But this wasn’t Roman Britain, the signature pointing to a more arid and eastern climate. The genetic analysis suggest a possible location, the steppes or area around Armenia. What was also notable was that the isotopes indicated another substantial change around the age of 9. With this in mind it’s unlikely that this was a Sarmatian cavalryman, or at least one bound to that redistribution of troops after AD 175. He was too young when first leaving his homeland, it also seems his journey took a number of years before he arrived in Britain. This doesn’t fit with the quicker movement you would have expected of redistributed cavalry. The burial also suggests that this wasn’t a serving soldier. It was a grave devoid of any distinguishing markers, no goods, not even a simple headstone.

Perhaps though he had an association the Sarmatians and his journey to Roman Britain intended to meet up with them in some capacity. Hopefully we’ll find out more but this is a wonderful and poignant story and a reminder that people of antiquity were more mobile than we sometimes think.

For more on Roman Britain why not check out my piece on Richborough or a bizarre mosaic on the Isle of Wight?