Ancient Greece thronged with holidays, sacrifices and events throughout the year. It’s no surprise that there was one such festival in the the mid-winter period. The Haloa was celebrated towards the end of the Attic month of Poseidon.

This corresponds to late December in the modern calendar. It was a festival where women were front and centre and expected to behave in a way you might find surprising.

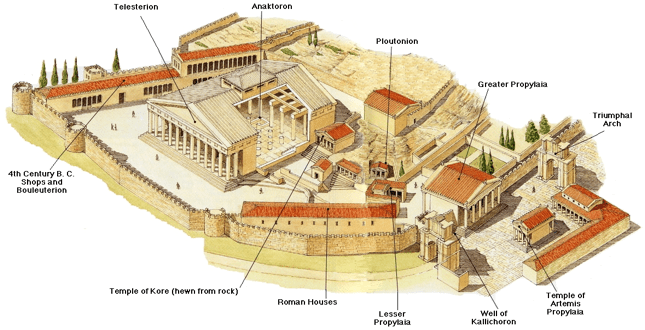

Eleusis, where it all happened.

Around 11 miles northwest of Athens is the site of Eleusis, famous for the Eleusian Mysteries. It was at Eleusis where the sanctuary to Demeter was to be found. This was a substantial site with several buildings as you can see from the illustration below.

The Haloa – how in unfolded.

Establishing an order of events and what happened at the Haloa requires some rudimentary detective skills. Much of our knowledge about it comes from references in source material. For example, that there was a priestess in charge is mentioned in a speech by the Athenian orator Demosthenes. Overarching this is a commentary written in the 10th century CE by a Bishop called Arethas. There are snippets of earlier sources referenced in this but as you might imagine, the Christian view of this was not one of approval. Even the most ‘civil’ of pagan festivals were given rough treatment at the quills of the time. The Haloa was nothing approaching this and must have drawn tuts and gasps aplenty.

The festival began with a sacrifice and it’s possible to use this as an anchor point to suggest an order of events. Sunset at Eleusis in late December is at 17:00, and as the sacrifice would have been made during the day it’s plausible for it to have featured in the mid afternoon. This would have allowed those travelling from Athens to make their way to to Eleusis. As mentioned, it was a journey of 11 miles and this gave enough time for those participating to make their way to the sanctuary and assemble there.

The main sacrifice was overseen by the priestess and it may have been a bloodless one, that is to say it didn’t involve an animal. Once the sacrifice had taken place women and men were segregated – there is debate as to what the men did, but of more interest is what the women got up to.

Drinking, feasting and behaving badly.

For women attending what came next was a pannychis, an all night feast. Women only festivals weren’t unusual, but here there is evidence that women across all spectrums of society were invited to celebrate. Prostitutes are mentioned engaging in some salty language with each other and this links in with a key theme of it all. Vulgarity.

Women, even virtuous wives, were encouraged to swear and discuss the sorts of things which would shock in everyday conversation. A word used here is aporreta, a word not easily translated though Brumfield suggests ‘shameful’, vulgar’ and ‘unspeakable’ as giving a rough indication.

The Telesterion, a large building, is suggested as a location for all the bawdy chat and for the feast itself. Here food and cakes shaped like genitalia (male and female) were washed down with lots of wine. Following the feast the action moved outside, though exactly what went on isn’t clear. An inscription dated to the 4th century BCE indicated 3 tonnes of wood was ordered for the festival. Suggestions of a massive bonfire, or seating to watch dances have been made but another is found on a kylix by the Oedipus Painter.

The cup dates to around 480 BCE. On it two women dance round a large phallus. It’s plausible that such structures were built and the wood was used in part for these and for a bonfire which would have been needed given the time of the year.

The question you may have is what function did the overtly sexual behaviour, the vulgar language and even dancing have? Why was it encouraged?

The Homeric Hymn to Demeter tells of how Demeter, after losing her daughter Persephone to Hades, wandered the earth as a mortal woman. She is described as a woman in mourning, which is understandable given her temporary loss. The goddess, still disguised as a mortal stopped outside the palace at Eleusis and here she was spotted by women from the palace to took her in and tried to cheer her up.

In Homer’s account this is eventually accomplished via some jokes which forced a smile on her face. However, in other myths it’s a bit more bawdy. In one a nurse made the goddess smile after flashing at her. In isolation this would seem a very odd version of the myth, but it’s plausible that the Homeric tale was merely a tamer version where it wasn’t vulgar actions, just vulgar jokes which raised the spirits.

Brumfield noted that aporreta featured in other rites associated with Demeter. As such the function of it as well as the behaviour in general was to jolt Demeter from her gloom and into action. With her spirits raised the fertility of the fields and the harvest was ensured for the period following. It must also have been a great social valve which helped ease any social tensions. Though it may have caused a few headaches.

The involvement of the men at the festival isn’t that clear. It’s been argued that they had their own celebration or that the segregation was only temporary and a joint celebration concluded the festival. However, the involvement of men does seem to have been secondary to the festival of the women.

This is echoed in the involvement of male deities. Both Poseidon and Dionysus are referenced as supporting characters in the festival. The latter has a more obvious connection, Dionysus had agricultural elements to his worship. He was the god of the vine and of fertility. Phalli featured at the Haloa and they were certainly a part of his worship also.

With Poseidon the association is more niche. Robertson argues how the god of the sea had involvement here through the ditches and embankments which were repaired at this time. In addition there was flooding of the fields and even an epithet of his (phytalmios which references the fertility of vegetation).

Podcast.

I recorded a podcast on the Haloa which goes into a bit more detail on the above. If you want to listen you can find Ancient History Hound on most platforms. The episode is titled ‘The Haloa, it makes Boxing Day seem civilised’. You can find episode notes for it here.

Further reading.

Allaire Brumfield, Aporetta, Verbal and Ritual Obscenity in the Cults of Ancient Women.

Noel Robertson, Poseidon’s Festival at the Winter Solstice, Class Quarterly Vo 34, No 1 (1984)

Evy Johanne Haland, Greek Festivals modern and ancient Vol. 1