Sardinian origins.

The ancient Mediterranean was flush with cultures which existed prior to and alongside the Greeks and Romans who often soak up our attention. On the island of Sardinia there were a people who came to dominate the skylines with their towers and demonstrated their skill on a much smaller level with their figurines. This was the Nuragic civilisation.

A towering culture.

The towers, or nuraghe, are the dominant cultural remains of the Nuragic people. It’s from these which the name ‘Nuragic’ has come to us. Ironically, we have no written records of them or their language. Instead Nuragic is applied from a 1st century AD inscription above a doorway in the nuraghe at Aidu Entos.

The Latin script refers to ‘nuraghe’ and it’s thought this was a pre-Latin word which was Sardinian in origin.

Initially the nuraghe were smaller and more simple in design. Around the 16th century BC the nuraghe emerged in its fullest form. This was a conical tower with a flat top and inside there were chambers, access to the higher parts of the tower was made via a spiral staircase.

In some instances a single nuraghe is present, but there are variations. There are some where a nuraghe is surrounded by dwellings. There are also those where several nuraghe along with bastions and walls form defensive complex with dwellings contained within.

Today around 7,000 nuraghe have survived, many not excavated and so perhaps we will be able to learn more about them.

Nuragic aristry.

Bronze figurines, provide a rare chance to understand the Nuragic culture further. These often take the form of warriors or hunters but added to this are animals, ships and a four eyed character, possibly a demon.

It’s argued that these were displayed at sanctuaries, as such they belonged to the public sphere. They were not items of personal wealth. The figurines were produced from the 12th century BC and were subject, as art often is, to shifts in styles. External influences are found in the very making of these works, both the copper used and the tools needed were traded from Cyprus.

Indeed pottery from the island of Cyprus has been found and so we need to remember that the Nuragic people were not isolated. They were knitted into the trading networks of the Mediterranean which itself acted as a way of cultures influencing and being influenced.

Food and diet.

Animal remains have been found in the Nuragic settlements, unsurprisingly the remains of goats and sheep were present. Pigs, boar, deer and even oxen were added to the dinner table. Excavations at the settlement at Santu Antine revealed that many of the animals eaten were domesticated with hunting sporadically adding to the menu. In the 10th century BC there is evidence of a wine making industry. The dinner table was now looking rosy, though perhaps not rose.

Carthage and Rome.

As with many locations in the western Mediterranean the island of Sardinia soon came under scrutiny from the powers of Carthage and Rome. It was the Phoenicians who settle Carthage and it was this trading power whose networks extended across the Mediterranean. Given the established trading links between Cyprus and Sardinia it would be implausible to think that the Phoenicians were aware of the Nuragi.

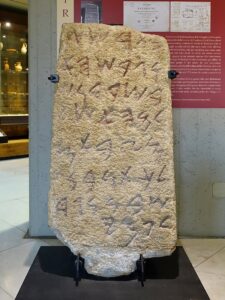

A direct link between the Phoenicians and the Nuragi can be found in the form of the Nora stone, which dates to the 9th century BC. The translation of the stele has been debated, though perhaps what is important here is that it provides a tangible link between these two cultures.

What happened next is again up for debate but there seems to have been a slow process of Phoenician involvement in Sardinia, perhaps initially through trading and then the establishment of trading posts. In the 8th century BC a the Phoenicians came proper to the island and established centres at Tharros, Sulcis and Nora.

Culturally it’s difficult to establish what the effect was on the Nuragi. Though it has been argued that the later figurines created were more in line with the eastern style.

In the 3rd century BC Sardinia came into ownership of the Romans. By this point it’s plausible to think that the Nuragi people had dwindled into a small population who were not considered worthy of much attention. The Nuragi may have claimed irrelevance to the Romans but not the Nuraghe. These were repurposed by the occupiers. In some cases they acted as storerooms and though mainly they were interpreted as residential with villas added alongside them.

Today the Nuraghe still stand, testament to the skill of the Nuragi, perhaps one day I’ll be lucky enough to visit one.

Virtual Tour.

Here’s what a visit to a Nuraghe complex may have been like.

Reading list/Contributing works used.

Cyprus and Sardinia in the Late Bronze Age: Nuragic table ware at Hala Sultan Tekke. Gradioli et al.

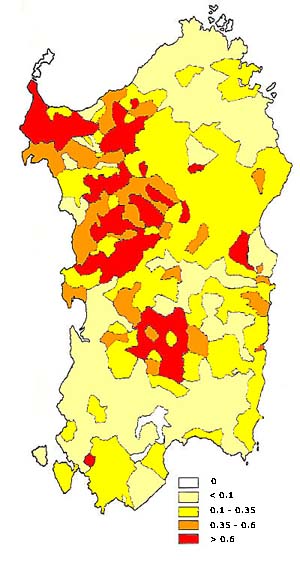

The Nuragic People: Their settlements, economic activities and the use of the Land, Sardinia, Italy. Anna Depalmas and Rita T.Melis.

Study of animal remains dug out during excavations of a Nuragic village in Sardinia. Portas et al

Phoenician colonization of Nuragic Sardinia. Jade Robison.

Chemical composition and lead isotopy of copper and bronze from Nuragic Sardinia. Begemann et al

Monuments, mobilization and Nuragic organization. Gary S Webster.

Beyond the Nuraghe: perception and reuse in Punic and Roman Sardinia. Alfonso Stiglitz.

Sardinia’s Nuraghi: Four Millenia of becoming. Emma Blake.

Sardinian bronze figurines in their Mediterranean setting. Ralph Araque Gonzalez.

The Nuragic civilization. Paolo Melis.

Carthage. Serge Lancel.