Cannae and extra bits.

I hope you enjoyed the episode on Cannae and the elements leading up to it even if it the subject was gruesome in places.

You will also have heard Luke aka The Bald Historian whose promo I played. You can find him on twitter @bald_historian and you can find his website here.

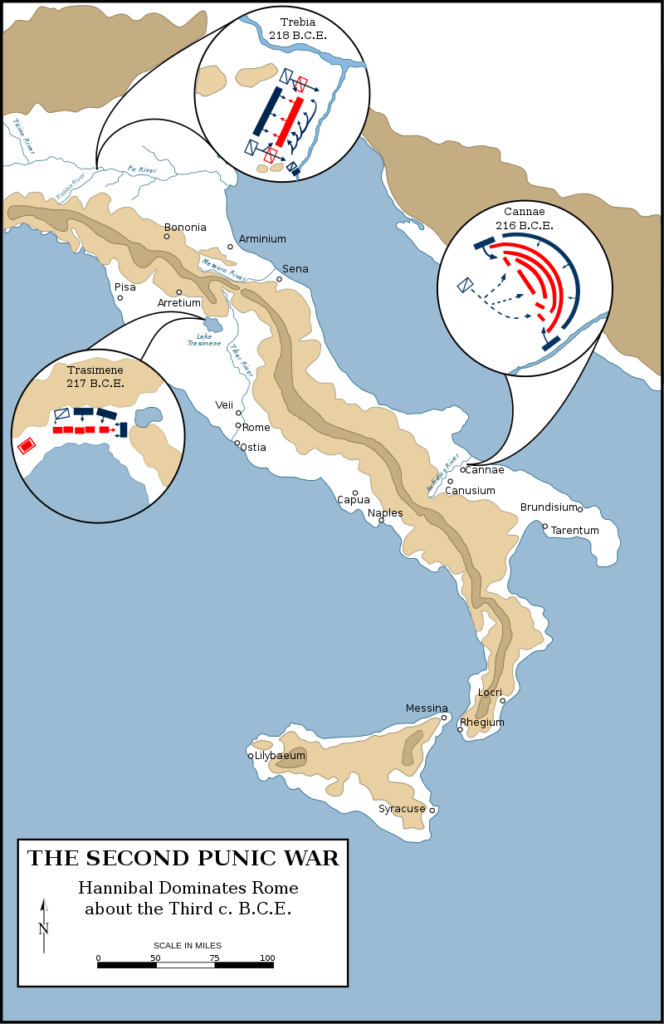

The location.

Here’s a great map detailing the location of Cannae, as well as the previous two battles.

The battlefield (thanks to Livius).

The Battle.

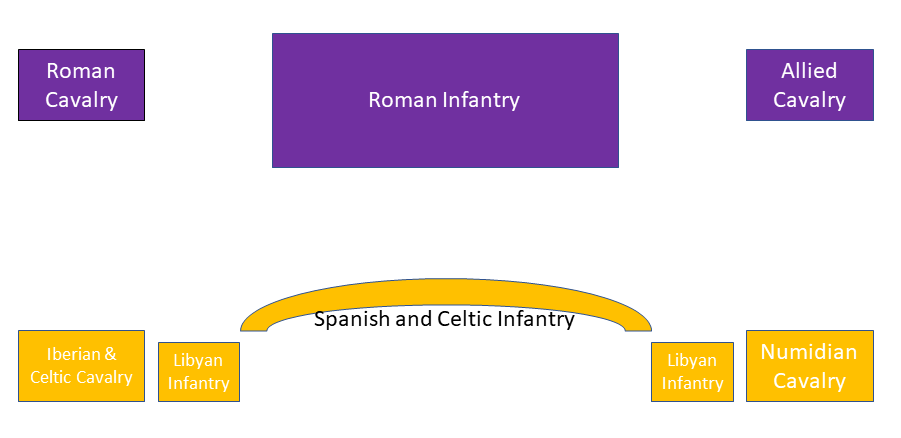

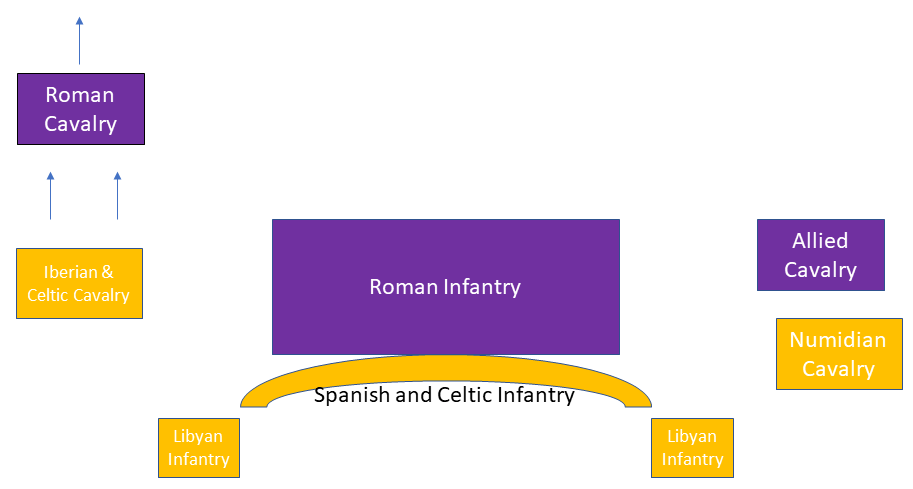

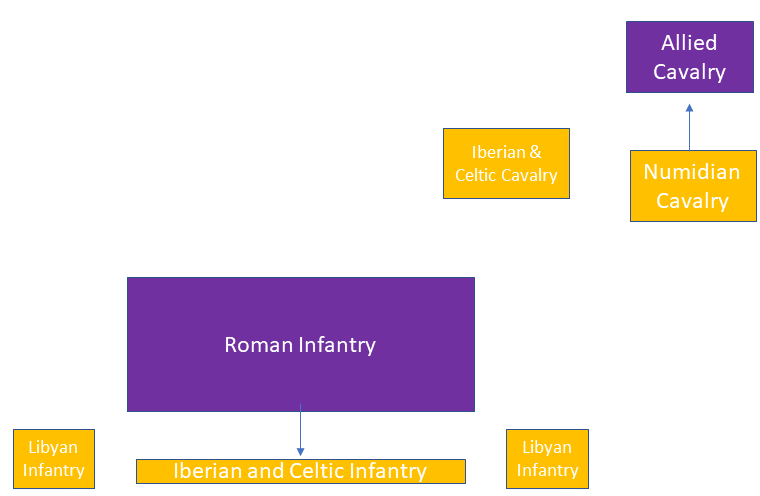

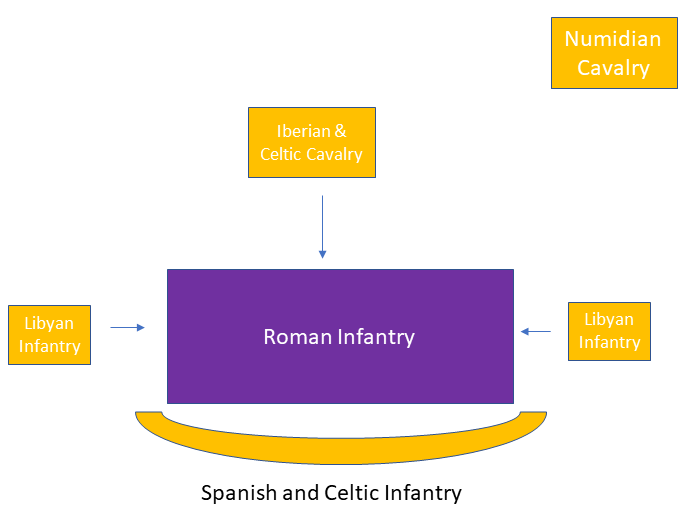

Hopefully this will help clarify my explanation in the episode.

1. The initial deployment.

2. The Celtic and Iberian Cavalry rout the Roman Cavalry.

3. The Roman centre forces the Carthaginian line back, the Iberian and Celtic Cavalry move across to support the Numidian cavalry who chase the Allied cavalry off the battlefield.

4. The Roman infantry centre has pushed the Carthaginian line back but is now exposed on the flanks to the Libyan infantry which hit it in the flanks. The Carthaginian line reforms as the Roman momentum stops. Now the Romans are boxed in and the slaughter begins.

Dictators and hammering.

In the episode I mentioned how dictators at Rome could be invoked for a range of reasons and my favourite was the ritual where they hammered some nails into wood. This is mentioned twice by Livy:

Bk VII.3.

It is said to have been discovered that the older men remembered that a pestilence had once been assuaged by the Dictator driving in a nail. The senate believed this to be a religious obligation, and ordered a Dictator to be nominated for that purpose. L. Manlius Imperiosus was nominated, and he appointed L. Pinarius as his Master of the Horse.

Bk VIII.18.

This in response to a spate of poisonings.

In consequence of the universal alarm created, it was decided to follow the precedent recorded in the annals. During the secessions of the plebs in the old days a nail had been driven in by the Dictator, and by this act of expiation men’s minds, disordered by civil strife, had been restored to sanity. A resolution was passed accordingly, that a Dictator should be appointed to drive in the nail. Cnaeus Quinctilius was appointed and named L. Valerius as his Master of the Horse. After the nail was driven in they resigned office.

Reading list/Sources cited.

The War with Hannibal, Livy. Penguin.

Histories, Polybius.

Feeding the ancient horse, Thomas Donaghy

Cannae, Adrian Goldsworthy.

In the name of Rome, Adrian Goldsworthy

The Fall of Carthage, Adrian Goldsworthy

Hannibal, Serge Lancel

The reality of Cannae, Martin Samuels

Dictator, the evolution of the Roman Dictatorship, Mark Wilson

Episode Transcription (some change were made on the day of recording but only a few!).

It’s one of the greatest victories of all time and if you were Roman, one of the biggest defeats. It was a battle which also cemented Hannibal as a truly great commander. But how did it happen, why did Rome do what it did and how did the sources use it? Join me as I talk about the Battle of Cannae in the ancient history hound podcast.

Hi and welcome to the ancient history hound podcast, my name is Neil and in this episode I’m covering one of the most talked about battles in ancient history. The battle of Cannae. This was the third of a series of battles which happened soon after Hannibal arrived in Italy. And if you wanted to know about the previous two then you’ll be happy to know I have recorded episodes on them. Self promotion aside it might be worth doing so because Cannae didn’t happen in a vacuum, and the previous engagements informed how Rome developed its strategy in the lead up to the battle and the battle itself.

Before I start you can find me on twitter as @ancientblogger and the podcast specifically as @houndancient. I also release ancient history content on TikTok as @ancientblogger and there will be a full set of episode notes with a transcription of it, maps and diagrams as well as sources I have used or cited in my research – you can find it on my website ancientblogger.com.

If you can rate or review this on the platform you listen to then please do – it makes a lot of difference to indie podcasters like myself.

Now in this episode I’ll be discussing some of the details of the battle, in previous episodes there wasn’t much to say about the nasty stuff. But here it’s a bit more descriptive, nothing too gruesome but I just wanted to mention it now. Also, unless I state otherwise it all the dates here are BCE, just saves on the voice.

Much like the episodes on Trebia and Trasimene the events in the lead up to the battle tell us a great deal, they allow us to see how Rome and Carthage dealt with new situations and give us so much of an insight behind the scenes as it were. Cannae is no different, although the lead up was a bit longer and has almost a narrative of its own. I’ll begin then with a brief summary of where we are and then the events and drama which lead to the battle.

Hannibal and his Carthaginian army had arrived in northern Italy in the autumn of 218 and in December defeated a Romany army at Trebia. This certainly got the attention of Rome and also some key allies in northern Italy such as the Celtic tribes.

In the following summer of 217, around 6 or 7 months later Hannibal struck again. After Trebia Hannibal moved south, he now faced two consuls each with an army and each positioned to intercept him. Avoiding one of the consuls he bypassed another and drew it out from its safe defensive position. He led it to a lake called Trasimene and this led to another Carthaginian victory.

And this is where we are, it’s the summer of 217 and Rome has not only lost another battle against Hannibal they were also in a state of political disarray and this was because they had lost one consul in the fighting at Trasimene whilst the other was many miles away with another army. There was no real leadership at Rome anymore. But Rome’s political system did have an option is such times as these. When circumstances dictated they could appoint a dictator.

The role of dictator was an old one, excusing the pun but almost as old as the hills Rome sat upon. Wilson provides a great summary about the dictator which I will quote “whenever an emergency – whether domestic, military, or religious – was not best solved by the magistrates already in power, the Roman people or the senate could call upon the consuls to cede superior executive authority to one individual suited by experience and temperament to resolve that crisis and restore Rome to its previous state of safety and stability”. Endquote.

It’s far different from our perception and use of the term in the modern world. Yet even within the timescales of ancient Rome things changed, after the Second Punic War, that’s the one we are dealing with now, Rome stopped using this office and it was picked up in the first century by Sulla and Julius Caesar. Shall we say they interpreted it very differently.

A dictator in the original sense was a trouble-shooter brought in to resolve an issue, these aren’t always recorded and are often vague. It might be simply to restore stability, or organise games, elections even a festival. My favourite rationale for invoking a dictator was to hammer a nail into some wood as part of a ritual, possibly to ward off disease. How would that have looked on your CV?

Dictators at this point then weren’t unusual and weren’t about a power grab. The man chosen for the role was Fabius Maximus.

Fabius was from the patrician class, the elite group of families in Rome. His great grandfather had defeated the Samnites and won the name ‘Maximus’ meaning ‘Greatest’ as a result. In many ways he was a sound choice, he’d been consul twice previously and possibly a dictator as well. So he knew the game, he was also approaching 60, so perhaps stripped of personal ambition and instead a mind driven to good outcomes to protect his legacy. A safe pair of hands.

Though Fabius was made dictator it wasn’t done in the conventional sense. At this point becoming one required either consul to appoint you and both of these were absent. Flaminius had been killed at Trasimene and the other consul, Geminus, was miles away with his army. In absence of the standard process the senate passed a law whereby he could be appointed and this detail wasn’t missed by Polybius or Livy who enjoyed the occasional dig that he wasn’t a proper dictator. Thank goodness they didn’t have twitter back then.

As I mentioned earlier a dictator was required for a specific purpose and this seems to have been balanced between providing someone to deal with Hannibal as well as occupy and oversee the necessary duties only a senior official could provide at Rome. Supporting a dictator was a second in command, called ‘the master of the horse’. Normally the dictator would appoint this but perhaps due to the unusual process to appoint Fabius the senate chose Marcus Minucius and it’s safe to say that these two did not get on.

Fabius’ first action was to raise two legions and meet up with Geminus to take his as well. Fabius now had between 30-40 thousand troops, but to call them troops might overlook a basic fact, namely that this was the definition of an amateur army. These men were either green or those who had been beaten by Hannibal. This was not an army in any fit state to take on the most basic of enemies, let alone a larger force boasting a far higher level of soldier in every regard.

Fabius’ assessment of what the Roman army could, or couldn’t do led to the nickname which he was to later become famous for, ‘cunctator’ or ‘delayer’. This wasn’t used in his lifetime and its somewhat ironic that a name which became so closely associated with Hannibal did so for never actually engaging with him. Instead Fabius employed a very different, almost un-Roman approach.

In the late summer of 217 Fabius took his army and camped near Hannibal who had moved further south on the eastern side of Italy, near modern day Foggia. He camped 6 miles from Hannibal who did his best to lure the Roman army out for a fight. Fabius kept to the plan, when Hannibal gave up and moved west Fabius shadowed him. Though this was an effective strategy it caused concern in the Roman camp and even more so it caused tension between Fabius and his second in command Minucius.

This theme of tension between those dealing with Hannibal isn’t something new. Perhaps it was genuine, perhaps it was to add to the drama or make a point. In the context of the latter it could emphasise the bad qualities of someone, such as Longus at Trebia or Flaminius at Trasimene. It’s certainly something which will raise its ugly heard later on.

The strategy Fabius pursued was eminently sensible and it’s worth considering why. Obviously there was the point about the abilities of the two armies. But that aside let’s consider the weaknesses of Hannibal’s army. There was the issue of momentum, from the moment Hannibal descended the Alps he’d been winning victories and this had added to his reputation and kept his troops happy, especially the Celts who were delighted to be killing Romans. Fabius didn’t want to offer up any more easy wins for Hannibal both on and off the battlefield.

And it was off the battlefield where Fabius saw he could do some damage. Something I’ve not spoken about much but logistics were and are a fundamental for any military operation of any age. Hannibal’s army numbered around 50,000 and it was a full time occupation to keep everyone fed and watered. What made this even more demanding was that contingent of cavalry. You see horses eat and drink a lot more than a person. To give some rough estimates a moderate sized horse, under 15 hands, needs around 20lbs of food and 30 litres of water a day. With around 10,000 cavalry that’s 200,000 lbs of fodder and 300,000 litres of water a day.

And this figure relates just to the cavalry. It doesn’t include the men or the hundreds of pack animals which would be carrying the supplies or used generally. Rome not only had fewer cavalry but their army could be easily supplied – they were the home team. Hannibal was therefore working on two fronts, to beat Romans in the field and keep his supplies from running out.

Fabius, by shadowing Hannibal, exacerbated the issue of logistics because he was able to hit any foraging party that Hannibal sent out. This had two effects, it began to whittle away at Hannibal’s far superior troops and also prevented him from helping himself to the local produce at will.

Hannibal’s response to this was to move west into the rich lands of Campania, and I say rich because these were agriculturally fertile and there was land here owned by the elites at Rome. Previously to this Hannibal had pillaged areas to get a response from Rome and so this move gave opportunity to restock and bait Fabius into a pitched battle.

Fabius had followed Hannibal and saw what he thought was a mistake. In order to access the Campanian plains Hannibal had moved his army through a pass. He’d need to use that same route on the way back, so Fabius set 4,000 men there and camped the rest on a nearby hill. And waited. If Hannibal tried to fight his way out he’d have a real problem, his cavalry wouldn’t be of much use and in such a good defensive position the Romans could either beat him or cause a lot of casualties. Either would end his campaign.

Now before I get to how Hannibal solved this riddle here are some words from a podcast you might be interested in.

Back to the conundrum, Hannibal was stuck in Campania and unable to get out through that pass which was now guarded. As his namesake in the A-Team, Hannibal loved it when a plan came together and though he wasn’t locked in a space with lots of convenient resources he did have a number of oxen he’d stolen. At night he sent a detachment of men along with 2,000 of the oxen up a hill near the pass. The oxen had wooden bundles attached to their horns and these were lit on fire. The Romans in the pass saw what they thought were the Carthaginians making a break for it and moved up out intercept. But they met a lot of angry cattle instead. As it was night there was a great deal of confusion, Fabius wasn’t sure what was going on but wouldn’t commit the greater army as fighting at night was something to avoid, especially if your army was inexperienced. As dawn broke the ruse became apparent – Hannibal had got his men through the pass. He even sent troops back to help the detachment who’d been make-do shepherds, they also killed a number of Romans in the process.

Needless to say the grumblings in the Roman camp against Fabius grew even louder but fortunately he was required in Rome to oversee some important religious rituals so he left the army in the charge of Minucius – the army now had a very different character in charge.

Minucius made for Hannibal who was using Geronium in the modern day region of Molise as his main supply base. It was now autumn and so thoughts turned less to war and instead to ensuring that Hannibal had enough supplies for the winter. Camping nearby it he engaged Hannibal in a minor battle, nothing spectacular, in fact Polybius was at pains to underline how a good portion of Hannibal’s men were foraging and bringing in supplies. As mentioned, these made them very vulnerable and gave Hannibal a dilemma. In order to defend his position he’d need to pour what troops he had into the fight. Again, remember that he didn’t have his full army at hand. Alternatively he could pull back to Geronium and concede the area to Minucius. He chose the latter,

This was greeted by Minucius and by those back in Rome as a major victory, and if you listened to the episode on Trebia you might remember the Consul Longus forcing a Carthaginian foraging party into retreat. Back then Longus had announced this in similar fashion, that he had dealt Hannibal a major blow. The reality back then and now was that it wasn’t even a scratch.

But Rome was desperate for any sort of good news and so Minucius became the man of the hour.

The response to this was to give Minucius equal charge with Fabius. This sounds odd and has been used to comment further on how Fabius’ wasn’t really a dictator in the proper sense. But anyway. The Roman army was split between the two, lets call them generals, and two very different ones at that.

Minucius, eager to capitalise on his quote-unquote victory made to attack Hannibal again but this time fell to an ambush. His forces were on the verge of annihilation but Fabius swept in with his army and was able to help Minucius retreat safely. Minucius was humbled, in fact the accounts are that he went to the tent of Fabius and apologised in full view of everyone, even calling him father.

With winter on the horizon the two forces settled into their defensive positions near Geronium. This was the time of year when the consular elections took place and presumably Fabius was needed at Rome to oversee these. Things were returning to some semblance of normality, at least politically, the two new consuls elected would take office in March and take on Hannibal. The two elected Consuls were Gaius Terentius Varro and Aemilius Paullus.

Both men were polar opposites of the other. Paullus came from an established family, whereas Varro was a new man – that is to say he was the first of his family to achieve such a high office. The election had not been without controversy. According to Livy Varro was a demagogue who appealed to the commoners having been one of them himself. Varro had even argued that the whole war was the fault of the nobility, the likes of Paullus, who had encouraged Hannibal to invade. It would be these two men, who had no great liking for the other, who would be entrusted with agreeing on a military policy to defeat Hannibal. And again here is this theme of discord I mentioned earlier.

Though the time with Fabius in charge hadn’t led to any victories lessons had been learned and foremost amongst them was that it was unwise to split a large force into two armies. At Trasimene this had been somewhat necessary as each consul and their respective army had been given a route to guard against. But now this wasn’t required and so Rome forged a single huge army, approximately 87,000 men. But who would command it? In peacetime you might have consuls commanding on consecutive months, but the reality was that each consul feared missing out. So command of the army was swapped each day.

Around June Hannibal moved from Geronium, he had gathered crops and knew that there were more to be found to the south. In fact there was a very nice place which had both supplies and would undoubtedly be somewhere the Romans would want to fight. A town called Cannae.

This wasn’t a location near Rome, it was around 309 km, that’s 192 miles southeast of Rome. It’s around the same distance from Memphis to Nashville in the US, Manchester to Portsmouth in the UK and Osaka to Mount Fuji in Japan.

Cannae is located on a large flat plain with a single river, it was a place where men farmed and did so in great quantities, not where men fought. The location itself is a comment on how this battle bucked the trend. At Trebia Hannibal had been able to hide a force of men and cavalry who pounced upon the Roman rear. At Trasimene the Romans had been ambushed before they’d even formed up. But here there was nowhere to lay a trap, no cover for an ambush. That didn’t mean it was without dangers. The flat plain was perfect for cavalry and so the early days at Cannae were of two forces eyeing themselves up from their respective camps.

The difficulty the Romans had was that now they needed to fight a set piece battle but the area around Cannae wasn’t exactly perfect for them. The flat ground made Hannibal’s already dangerous cavalry that bit more daunting. For a few days the two forces eyed each other up whilst the two consuls debated what to do. The sources paint Paullus as resisting confrontation with Varro eager to get hold of Hannibal once and for all. It’s difficult to know to what extent this was the case. As you have heard Varro was demonised by Livy and falls into the trope of the commander who was overconfident and whose pride wasn’t checked by his ability. It was more likely that both of the consuls wanted to fight, after all that’s what they were there to do. But perhaps differed on when and how.

Even if Varro was strongly advocating for battle this doesn’t mean he was inherently wrong. Rome, even with its limitations, had a lot going for it – let me unwrap that point a bit.

Previous defeats by Hannibal had been underpinned by a shock attack. The hidden units at Trebia and the large scale surprise attack at Trasimene. But at Cannae the Romans could see his army and they knew they would be facing it as a complete unified force with no nasty surprises. This would be a battle in the more traditional or normal sense.

And then there was the numbers. At Cannae Rome could afford to leave 10,000 soldiers to guard the camps and still have 20,000 more men lining up. The larger numbers were also found in a type of soldier which Rome relied on, infantry. The minor success stories at Trebia and Trasimene had been where a unit of infantry had punched through the Carthaginian line. Of course the rest of the Roman army was being routed but it underlined the point that Rome could use its infantry to break the Carthaginian line. Even at their worst this tactic worked. I suppose the thinking was that without a surprise or ambush the infantry would be left to do the one thing it had done even in defeat.

Up until this point I’ve not gone into what the units in each army were, mainly because it made more sense to detail them now. I’ll start with the Romans.

When it comes to understanding the Roman army at this time we need to be mindful that there aren’t an array of sources which provide much detail. Unlike the armies of the later period we don’t have a wealth of evidence to understand how the Romans fought and what equipment they had. Possibly our main source for this is a good example of what I am talking about. It’s Polybius, whose account of Hannibal’s invasion of Rome is considered as good a surviving source as any, certainly more accurate than Livy.

Polybius was writing in the middle of the second century, that is some 60 years after Cannae. His description of the Roman army of the time is as close as we can get and though it may have different in detail it provides us with a base to work with.

The Roman army was predominantly infantry based, with the poorest taking up the role of skirmishers or velites. These had not much more than javelins and at best looked to counter the enemy skirmishers and provide cover when the army was forming up. When the Roman army did form up it did so three lines, each consisting of a different infantry type. At the front were the hastati, these were the younger men. As the army wasn’t professional there wasn’t standard kit provided, but a hastati was required to supply himself with light infantry gear. This would have consisted of a helmet, a shield, javelins and a sword. For body armour it might be just a tunic or wearing a small metal rectangle over the chest.

In the second line were the Principes. These were men in their late 20s who occupied the role of the heavy infantry. Their gear was much the same as the hastati except they would have chain mail, assuming that they could afford it. As they were older they were in theory more experienced, though exactly how experience can align to an amateur army is debatable.

Finally there were the triarii. These were older men and equipped like the principes but with a spear. Their main role was not to hopefully be involved as they formed that final third line. A saying went in Rome along the lines of ‘down to the triarii’ which essentially meant you were in a bad place. If the triarii had to get involved it meant the two lines in front had failed.

Romans fielded cavalry, though this was largely through property qualification and by that I mean people who could afford a horse. As such we can only guess at how skilled they were but they don’t seem to have been particularly effective. Much like the rest of the army these weren’t professionals, the men fighting at Cannae had very little experience and though their numbers were impressive it was certainly quantity over quality.

Rome could also call upon allied troops from the cities and towns which it had come to absorb. From this they were supplied with various infantry and cavalry, the latter specifically mentioned at Cannae. However, these were questionable, not so much in their ability but whether they were that bothered to fight for a people who had commanded them to do so. These were not men largely fighting for Rome and as such they were not to be wholly relied upon. Hannibal had taken care in his victories to let allies, or non-Romans go free after a battle. It was part of his overarching policy of detaching Rome from her allies and so it may have been that there were soldiers lining up who whose commitment to Rome was minimal.

Against these were arrayed the army of Hannibal. In every sense these were the opposite, they were veterans and many had been marching and fighting since they left Spain in the summer of 218. They were truly an international force, to start with there was the Libyan or African infantry. It’s debated whether these were spear based or sword based, the fact that they equipped themselves with Roman weapons following the victory at Trasimene has been interpreted as evidence of them being a sword based unit. In either case they were highly skilled and by this point very experienced.

There were also Iberian troops. Hannibal had spent his formulative years in southern Spain and had both fought and recruited from the tribes there. The tribes in Iberia practised a martial culture, that is to say they were largely about fighting. These were great swordsmen and along with the terrifying falcata, look one up and you’ll see what I mean they also carried with them a type of sword which the Romans would later adapt and call the gladius.

The Celts were the final infantry type and these had joined up when Hannibal had won at Trebia. These fighters had a grudge against Rome every bit as much as Carthage had. Being able to recruit and keep these men happy had been a much needed coup for Hannibal. They were much easier to replenish and this seems to coincide with their use, Hannibal was happy for them to take the brunt of much of the fighting thus keeping casualties down in the units he couldn’t so easily replace.

For skirmishers Hannibal could boast the Balearic slingers, trust me, these could keep a unit pinned down and cause havoc with their lead or stone missiles. They could also use javelins.

Finally there was the cavalry. The heavier type belonged to the Iberian and Celtic, very good riders who would hit hard but the jewel in the crown was the Numidian cavalry. These were the polar opposite of the Celtic and Iberian horse, they were smaller horses whose riders darted in and out throwing javelins. Enemy horse had trouble dealing with their mobility and men had no chance. Were they to get round a flank they could throw their javelins point blank into the side or rear of an an enemy causing panic at will.

And this is a really important point to consider. Panic in an army could easily lead to rout with a unit of men or larger units dissolving into a bunch of fleeing individuals. It could easily lead to a domino effect throughout an entire army which simply collapsed. No surprise then that battles in antiquity were about inducing this state as much as possible. The appearance of an enemy to the rear or surprise could ignite it. The more experienced an army the more tolerance there was of it, which is why experience was so vital. Experienced soldiers understood the impact of that first charge or engagement. They expected it. Contrastingly an inexperienced army of unti of men might find themselves fleeing after the first engagement.

The two armies were therefore a fascinating contrast, in terms of composition, numbers and experience.

On the 2nd August 216 the two armies marched out with the sources explaining that this was Varro’s turn to lead the army. The exact battlefield has been disputed but the sources give a good account of how the armies deployed that day and it seems that Rome set up facing south, it’s right wing hugging the river. On the Roman right wing was Paullus leading the Roman cavalry which numbered approximately 2,400 horse and Goldsworthy has estimated that the frontage of this measured 360 metres and 40 metres deep. Imagine 4 American football pitches end to end. That’s what you would have been looking at. In the Roman centre was that massive block of around 50,000 infantry with the Hastati at the very front.

This occupied a front, again estimated by Goldsworthy, measuring 1 kilometre or 0.6 miles and though the sources don’t provide a specific distance they do emphasise that the infantry were bunched up in a much narrower formation. There were likely several reasons for this. The first was that it kept things simple, these men were as green as the surrounding countryside. Anything other than marching forward could lead to confusion. The deeper lines of infantry also gave the army more momentum, this was vital to push through the Carthaginian line. Perhaps it also gave the men a sense of security.

There’s also the argument that this was because the plain they fought on as narrow. On the west side the river and the eastern side some form of obstruction, perhaps rocky ground. In either case this was a dense brick of an army.

Moving across the the Roman left wing were the 3,600 allied cavalry led by Varro and as I mentioned it with the Roman cavalry it only feels fair, these covered a front of 540 metres. Adding these up Goldsworthy has give an entire front for the Roman army as just under 2 km.

Against this was Hannibal’s army of around 50,000 men and as you’ll hear this differed in more ways than just numbers. The composition was markedly different. On the left wing, that is the Carthaginian wing next to the rive and facing Paullus and the Roman cavalry were a mix of the Iberian and Celtic cavalry. Goldsworthy estimated that this numbered between 6 and 7 thousand and so straight away you can note how they outnumbered the Roman horse opposite.

Next were the Libyan infantry, these may have been deployed just behind the cavalry on either side or certainly not as part of the main front line. Again, speculation suggests that there were 10,000 of these split between the two placements either side of the main centre.

Hannibal’s centre was formed of around 4,000 Iberians and 20,000 Celts. This against possibly 50,000 tightly packed Roman infantry. But here’s where it gets curious. Normally there would be flat lines of men, but the Iberians and Celts formed a crescent which bent out towards the Romans. This was a decisive feature of the battle, so make note of it.

The other side of the crescent was supported behind or had the second unit of 5,000 Libyan troops and on the right flank 4,000 or so of the Numidian cavalry.

Deploying the armies on both sides would have taken time with the skirmishers in the centre covering the troop movements and engaging with each other as a sort of prelude. It would most likely be late morning before the battle started.

The initial clash was between the two sets of cavalry beside the river, the Celtic and Iberian left wing versus the Roman cavalry on the Roman right. This was reported as being unlike a standard cavalry engagement and the fighting either taking place in a static way or possibly with the soldiers dismounting and fighting on foot. The outcome was certainly clear with the Romans roundly beaten and forced into retreat.

On the right the Numidians did what they did best, they darted around the Allied cavalry. When the Allied cavalry saw the Iberian and Celtic cavalry moving across to engage them, fresh from routing the Roman cavalry, the Allied cavalry just left the battlefield. The Numidian cavalry chased them off the field just to make sure and left the heavier cavalry to regroup and catch a breath. But they would soon be joining in again, we’ll hear of them shortly.

In the centre the Roman steamroller marched on and started to engage with that thin Carthaginian crescent. It may have been the the centre point of the crescent, the top of the rainbow as it were attracted the Romans who channelled and funnelled in making them more narrower in terms of composition.

Soon the sheer physics of the situation took effect, that momentum started pushing the Carthaginian crescent back, the troops there doing everything they could to keep formation and not break. This intensified as more Romans joined contact and the crescent was now inverted and beginning to fragment. Rome was dominating and doing exactly what it had planned to do. But ironically Hannibal had counted on this, because what Rome wasn’t aware of was that it had now pushed through the Carthaginian centre and between those two units of Libyan infantry who had been waiting. They turned inwards and bit into the sides of the advancing and disordered Roman infantry which was now even more narrowed through that gap in the centre. These were Roman soldiers who were pouring through the gap at the fracturing Carthaginian line and who thought they were moments from victory.

Clamped between these two units on either side the Roman centre stopped almost immediately and the Celtic and Iberian centre slowed their retreat, further boxing the Romans in. To the rear the Celtic and Iberian horse causing horror amongst the Romans. An entire Roman force of 50,000 or so men were now cramped into a small space. If you were in the middle or at least not on the edges you could only listen to the screams and wait your till enough men fell in front of for it to be your time. The butchery lasted hours with Hannibal most likely having to rotate his men due to exhaustion.

Livy painted a truly horrific scene the following morning. Men, some still alive offered up their throats knowing that there was not surviving their wounds. He also noted that some had dug holes in the earth with which to suffocate themselves. Those 10,000 Romans guarding the camp were soon captured.

The consul Paullus who had commanded the right wing had fallen. Livy recalling how he was offered escape but chose to stay and fight to the death. Though as you’ll hear shortly Livy was happy to create moralistic vignettes at time such as these to highlight certain values. Paullus wasn’t the only big name to fall that day. The consuls from the previous year both fell and Minucius also met his end. 29 military tribunes and nearly 80 senators or men Livy wrote as being from this class also perished. Though this obviously comes with a caveat that these are reported losses, with a lot of battles in antiquity numbers aren’t always exact.

Hannibal’s losses were minor in comparison. 4,000 Celts and 1,500 Iberians and Libyans and a few hundred cavalry. This underlines how steady and well disciplined that slow retreat was in the centre. And this is why Cannae is held in such high regard, each component of the army had a very specific role and if this wasn’t performed the outcome would have been very different. It’s distasteful to consider it in such terms but it was a near perfect battle, a slaughter facilitated through watchwork engineering. Each tiny piece doing its job.

There were some survivors from the disaster. Varro had escaped and a few young nobles including a certain Scipio were able to make a break for it. This was the Scipio whose father had been injured in the lead up to Trebia. Livy renders him in a heroic scene where he champions all the noble Roman virtues and this presumably is part of his character development as he is the famous Scipio, the one who will take the fight to Carthage and defeat Hannibal at Zama many years later.

For those captured, including the Romans guarding the camp, things were different. Hannibal allowed them to select 10 from amongst them who swore an oath to visit Rome and issue the ransom demands. When they arrived in Rome things were emotional to say the least. And then up stood Titus Torquatus Manlius who gave them a verbal kicking. Chief amongst his annoyance was that many refused to join in with a breakout made by Sempronius. The answer was therefore no, we won’t ransom those who failed to try and escape and instead expected to be saved. This feels unduly harsh but this is Livy. He was a historian writing around two centuries after all of this and he’s not a historian in the sense we might understand.

As I have mentioned, Livy’s account of Hannibal and his interactions is punctuated with dramatic narratives. These result more from his need to point out the moral standards of characters, rather than the accuracy. So what we have are narratives and episodes where particular characteristics and attitudes which he saw as desirable for a wholesome Rome, and perhaps lacking in his day, were underlined for the reader. This is probably one such instance, a group of soldiers who had neglected to fight and even to attempt to break out but expected Rome to save them. Even more so this is contrasted with the noble Scipio who won’t accept defeat.

This is also the point at which the biggest criticism aimed at Hannibal roams into view. That now he had to hit Rome and with it win everything. But he didn’t and Livy includes the famous criticism made of him by Maharbal, commander of his cavalry this was that he knew how to win a great victory but not how to use it.

At best this feels disingenuous and at worst a fabrication. In previous episodes I have pointed to Hannibal’s strategy which was aimed as disconnecting Rome from her allies. The great resource Rome had was its wealth and manpower, both secured in part from a number of cities in Italy who paid tribute in some form. Hannibal’s policy seemed to aim at reducing Rome’s influence in Italy and negate its hegemony.

The last thing Hannibal had the means and appetite for was a protracted siege. He lacked the men needed, the specialists and the equipment. Early on in Spain he’d spent months trying to take Saguntum which was a far easier task than Rome with its defences. This also bucked against what his army did, it needed momentum. Were he to sit outside Rome for possibly a year or more those Celts would soon leave and he’d be highly vulnerable. Hannibal’s army wasn’t the type to make an assault on a middling city, let alone one the size of Rome and with good defences.

Following Cannae there was more panic at Rome and another dictator elected. Cannae had an effect on Rome at every level. Most families now knew of someone who had fallen in the fightin, the loss of so many of the higher classes resulted in a new draft of Romans being given entry into the Senate. And then there was the loss of prestige. Perhaps the allies to the south of Rome were unconvinced by the two previous victories won by Hannibal. These, after all, could be reworked as unfortunate losses where Rome came a cropper due to sneaky opportunistic tactics or a bad general or both. But here Rome had been soundly beaten doing what it was good at. There were no excuses and a number of important cities in the south defected to Hannibal.

Cannae was absolutely catastrophic for Rome in every sense, and yet things were far from over. Rome refused to surrender, it wasn’t going to give up and in a sense this bucked the trend or certainly the expectations of it. Hannibal prowled to the south for another decade whilst Rome found ways to turn the tide and it must have done so with lessons from Cannae etched in its mind.

Possibly in a future series I may pick up on this but for now I’m somewhat done with all the death and rancour. I hope you have enjoyed listening to the episode and again I really appreciate you taking the time to listen. I imagine you must have a large number of podcasts sitting on the proverbial pile, so thanks for taking the time to listen to me.

Until the next episode, which will certainly be cheerier and on something very different, take care and keep safe.