Tyrants formed much of the background to this episode so I hope you didn’t suffer from tyrant fatigue! Here are some extra bits which I hope will help you enjoy the episode more.

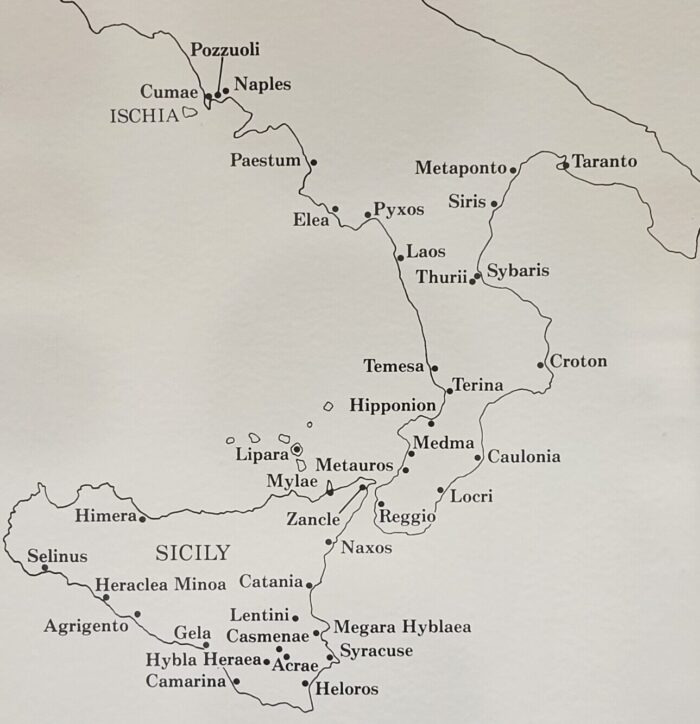

Maps.

Below you can make out the wider Greek world around Sicily and how those colonies were networked.

In the episode I mentioned how close Rhegion was to Zankle/Messina – this NASA image gives a great perspective. The strait of Messina is only a few kilometres, a bridgehead between Sicily and Rhegion.

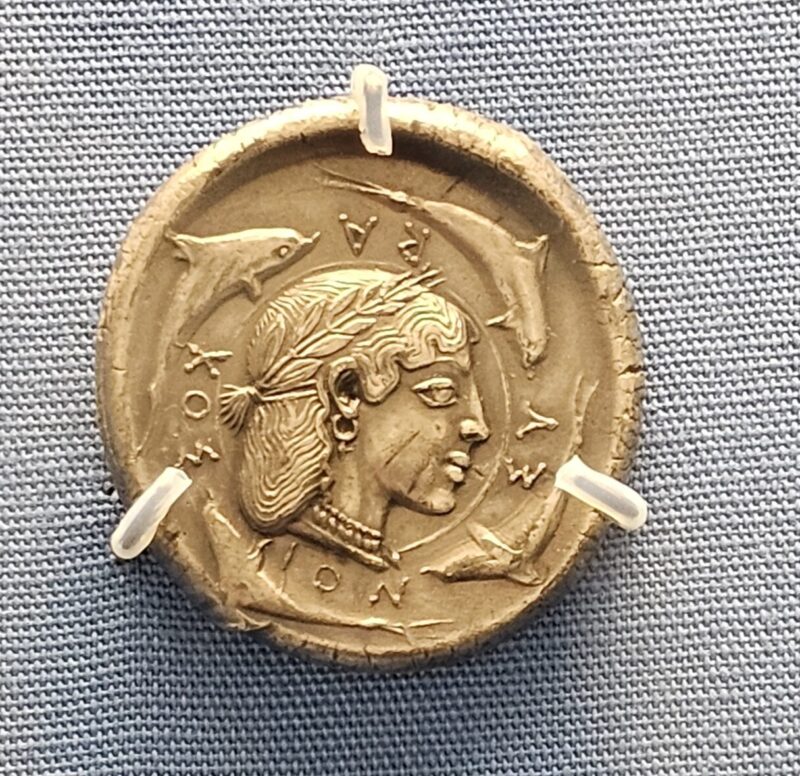

Coin of a tyrant.

This wonderful coin is a decadrachm from Sicily. It’s thought to be the ‘Demaretion’, dated to 490 BC linked to Demarete, Gelon’s wife. This is debated and may date to the 460s BC. If you want to see some more coins from the Sicilian colonies – have a look at a recent post I put up.

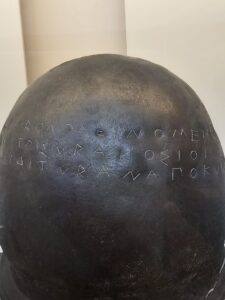

Spoils from Cumae.

I came across this at a recent visit to the British Museum, one of the helmets from the Battle of Cumae in 474 BC.

This was one of the helmets dedicated by Hieron at Olympia and carries the following inscription:

“Hieron, son of Deinomenes, and the Syracusans, [dedicated] to Zeus Etruscan [spoils] from Cumae”

Reading list.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War.

Herodotus, Histories.

Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica.

Polyaenus, Stratagems of War.

Pindar, Odes.

Bacchylides, Odes.

Balco, W. Thinking beyond imitation: Mixed-style pottery in ancient western Sicily.

Booms,D. Higgs, P. Sicily culture and conquest.

Croon, JH. The Palici: an autochthonous cult in ancient Sicily.

Dominguez, A. Greeks in Sicily in ‘Greek Colonisation and account of Greek colonies and other settlements overseas’.

Falsone, G & Sconzo, P. New investigations in the north-east quarter of Motya. The archaic cemetery and building.

Lentini, M. Recent investigation of the early settlement levels at Sicilian Naxos.

McGlew, J. Tyranny and political culture in ancient Greece.

Miles, R. Carthage must be destroyed.

Morgan, K. Pindar and the construction of the Syracusan Monarchy.

Nigro, L. Temples in Motya and their Levantine prototypes: Phoenician religious architectural tradition.

Nigro, L. The sacred pool of Ba’al: a reinterpretation of the ‘Kothon’ at Motya.

Nigro, L. From Tyre to Motya: the temples and the rise of a Phoenician colony.

Nigro, L & Spagnoli, F. Landing on Motya.

Nigro, L. Before the Greeks: the earliest Phoenician settlements in Motya – recent discoveries by Rome.

Nigro, L. The Temple of Astarte “Aglaia” at Motya and Its Cultural Significance in the Mediterranean Realm

Orsingher, A. The ceramic repertoire of Motya: origins and development between the 8th and 6th centuries BC.

Pownhall, F. The making and the unmaking of the memory of Gelon of Syracuse.

Prag, J. The indigenous languages of ancient Sicily.

Sconzo, P. The Archaic Cremation Cemetery on the Island of Motya. A Case-Study for

Tracing Early Colonial Phoenician Culture and Mortuary Traditions in the West

Mediterranean

Shepherd, G. Archaeology and Ethnicity. Untangling Identities in Western Greece.

Tribulato, O. Archaic and Classical Inscribed Epigrams from Sicily: Language and Archaeological context.

Tribulato, O. Learning to write in Indigenous Sicily. A new abecedary from the necropolis of Manico di Quarara.

Tribulato, O. ‘So Many Sicilies’

Walsh, J.St.P. Urbanism at classical Morgantina.

White, D. Demeter’s Sicilian Cult as a political instrument.

Tyrants & Tragedy: Transciption.

Hi, my name’s Neil and in this episode, I’m continuing the story of ancient Sicily. In part One New Neighbours I gave an overview of the island’s history up to and including the early Phoenician and Greek colonies. This took me through to the end of the 7th century BC. In this episode I’ll be introducing a couple of new colonies and a lot more action which takes us from 600BC through to the middle of the 5th century BC.

Before I begin the standard appeal for any reviews or such you can give on the platform you are using to listen to this. There’ll be a set of episode notes on my website – ancientblogger.com which will include a transcription, reading list and sources used. There’ll also be maps and anything else I think might help.

As for social media – you can find me on Instagram, TikTok, youtube and X as ancientblogger. This podcast also has its own X account – @HoundAncient. I’m always eager to hear from you so feel free to get in touch and if you are old school enough to consider emailing then ancientblogger@hotmail.com is where you get me.

Ok, that’s it so let’s head on with the episode.

It wouldn’t be fair to start without giving the briefest of overviews as to where we are. It’s 600 BC and Sicily has three main cultural groups on the island. First up are the indigenous Sicilians. Now in part One I mentioned how the names often used for this group, Elymians, Sicanians and Sicels, is problematic given that they are labels Thucydides’, the 5th century BC historian, allocated. Though these labels do help to distinguish this group from others, and establish that there were different regional differences, there are issues as to how accurate they really are. After all they were created in accordance with how Thucydides understood the ethnic layout of Sicily. Many of the papers and articles I’ve read have this caveat when they use them. I’m going to continue as per episode One and refer to the indigenous people of the island as indigenous, Sicilians, locals, local tribes you get the idea.

The next demographic are the Phoenicians, in the 8th century BC, they had established a settlement on the western tip of the island called Motya and this grew into a substantial location.

Finally, we have the Greeks who largely settled their colonies on the east coast. Though I use the umbrella term of Greek these were colonies founded by different Greek city states. These inherited the rivalries of their parent cities and were often in strong competition with each other. On the eastern coast there were colonies such as Syracuse and Naxos. But there were also colonies elsewhere. On the northern coast was Himera, notable because it was quite near the western end. One colony we will hear a lot of is Gela, situated on the southern coast but more towards the eastern end.

To these settlements I need to add a couple more. The colony of Megara Hyblaea was another colony on the eastern coast, just north of Syracuse. The name of the colony gives away where the settlers came from, Megara in mainland Greece. The settlement seems to have been founded in the latter quarter of the 8th century BC so perhaps shortly after Naxos and Syracuse. The settling of this colony doesn’t seem to have been a simple affair, Thucydides’ wrote that the Megarians were joined by Chalkidians who finally settled the colony once a local king had given them land to do so and this king was called Hyblon. Megara Hyblaea therefor took his name; we could of course argue that this was a retrospectively applied myth which explained the name – but even if true it still posits that it could be easily believed that colonies were settled with some form of co-operation from the locals.

Megara Hyblaea joined with the practice of settling its own colonies and the result was Selinus. The exact details behind this aren’t clear, though Thucydides wrote how Megara Hyblaea had asked its parent city for assistance in this sub-colony. As to the date, this too isn’t clear though archaeological records suggest that by the mid-7th century there was a Greek presence at that location.

On the topic of location – Selinus was unique in this context. Where most Greek colonies had been in the eastern third of the island Selinus was almost at the western end of the southern coast. This was deep into what might be considered the Phoenician region, and this has prompted queries into why you’d choose that location. Was it some sort of aggressive posturing? Perhaps, though the answer was probably due to the lack of space in the eastern third of the island and the commercial advantage of being located nearer to Motya where it could literally set up shop and access that market as well as the indigenous settlements nearby.

The final two colonies, much like Selinus, were sub colonies. In 600 BC Syracuse added Camarina to the south of it, and this I’ll be mentioning later because this is a good example of how the parent / sub colony relationship can degrade. Finally, in or around 580 BC there was Acragas. This was a sub-colony of Gela and sat roughly in the middle of the southern coast. Today it’s known as Agrigentum.

Now, so far, I have probably given you the impression that founding a colony was an easy thing. Just turn up with a bunch of people and there you have it. That wasn’t always the case though and one example dated to the early 6th century and another towards the end of it show what can happen when it all goes wrong.

Diodorus Siculus, a Greek historian born in Sicily in the 1st century BC, wrote an account of Pentathlus who arrived on the western part of the island with settlers intending to found a colony there. The date mentioned by Diodorus was the 50th Olympiad which gives us a period of between 580-576 BC. When he arrived, he found Selinus in conflict with Egesta – modern day Segesta, an indigenous settlement in the western corner of Sicily. Pentathlus threw his lot in with his fellow Greeks of Selinus but fell in the fighting and the remaining settlers decided to leave.

Later that century a frustrated Spartan prince called Dorieus also tried his hand at setting a colony in Sicily. When his father died, he contested the throne with his elder half-brother Cleomenes. But it was Cleomenes who was successful. Dorieus, realising that he was unlikely to ever become king set his eyes overseas. After a failed attempt at a colony in Libya he headed west and to Sicily, and specifically the western tip area of it. However, when he arrived, he was defeated by a mixed force of Phoenicians and local tribes. This was said to have occurred around 510 BC. Just a bit of trivia about Dorieus, he had a younger brother who also died fighting non-Greeks outside Sparta, a certain Leonidas who met his end at Thermopylae.

To these accounts we can add the inscription dated to the mid-6th century BC of a fallen Greek named Aristogeitos who was buried at Selinus. The inscription records how he fell in fighting at the walls of Motya – though as no context is given, we don’t know the reason for this. These are scattered accounts but share common ground in where the action happened, western Sicily. Nothing substantial can be argued from this in terms of major relations, though there is the sense of the Phoenicians backing their local neighbours. The likelihood of small skirmishes between groups was high given that there were groups competing for resources and land. Disputes were often settled this way. Perhaps where Pentathlus and Dorieus went wrong was assuming that they could settle where they wanted without performing what we might now term the correct due diligence.

Though a lot occurred in the 6th century BC I want to pick up on two main events, one affecting the Greeks and the other Motya. Though in truth they affected the whole island. The first takes me to Acragas, the Greek sub-colony of Gela and to around 570 BC. It was here where an individual called Phalaris made a play for sole power. According to Polyaenus this individual had been a tax collector and the people of Acragas trusted him with building a new temple to Zeus. Phalaris happily took the money given and started construction; he bought the materials needed but also a large number of workers. I say workers, but these looked more like mercenaries and prisoners, that’s because they were. When the right moment came Phalaris used them to seize control and made himself tyrant of Acragas. He lasted until 554 BC when a revolt ended both him and his reign. This was often the fate of tyrants, not always but often. A quote attributed to Solon sums this up neatly. Being a tyrant was a good place to be but a hard place to get out of.

Aside to his use of deception, Phalaris’ main claim to fame, or perhaps infamy, was the brazen bull, a hollow bronze bull which a person was placed into and a fire lit underneath. The brief account of Phalaris contains many familiar elements found in other accounts of tyrants. There was the deception and trickery, often employed to seize power. Also cruelty. The image of the tyrant became a byword for bad deeds and corrupted power, and this is certainly the usage of it today. Yet things weren’t always that way, the relationship a tyrant had with his city and people might be beneficial in some ways, it could also exist without the cruelty and in some instances, they were widely praised. I’m planning to do a minisode on the Greek tyrants where I will expand more on those points, so keep an ear out.

The tyrants of Sicily had something their counterparts elsewhere in Greece often did not, non-Greeks as neighbours. Where in mainland Greece a tyrant might be restricted by the boundaries of his city state on Sicily there was not such restriction. This led to the likes of Phalaris and other tyrants campaigning to grow their lands, usually this was at the expense of the locals. But as you’ll hear, not always.

At the western end of the island the Phoenician colony of Motya might have looked across and arched an eyebrow. Could the emergence of tyrants cause them an issue? What might happen if a few formed a power block and decided that Motya was on the menu?

So it came to pass that Motya was attacked in the middle of the 6th century BC, and it was captured. Not by a Greek tyrant though, in fact not even a Greek. Instead, the invasion came from across the sea and another Phoenician colony on the rise, Carthage.

It was around this time that Carthage started to flex its muscles and influence the Phoenician colonies of the western Mediterranean. Motya may have been targeted because it was a strong rival and occupied a very good location. Its strategic importance made more so because of the significance of Sardinia at this time to Carthage. There were possibly a number of good reasons why Carthage made this bold move.

A layer of burnt debris dated to 550 BC is found across Motya and this is the tell-tale evidence of citywide destruction. But out of this ashen layer archaeologists can also point to growth. Once the city was taken a mass building programme took hold in Motya. The Carthaginians had come to conquer but also to improve. The decades following the capture of Motya it received its first full set of walls. The Kothon sanctuary which I spoke about in episode One had a complete makeover, the all-purpose warehouse building levelled and a circular wall around the sanctuary built to highlight the importance of the sanctuary there. The temples were rebuilt and in the case of the temple to Astarte re-orientated and move 3 metres to the south. The sacred pool was formally lined with stone – as an aside it has been argued that this became a sort of star map, the night reflections upon it being used to chart celestial movements.

Other areas you might remember such as the acropolis were reset and the Cappidazzu sanctuary to the north had the temple, possibly to Melquart made grand. By the late 6th century Carthage was now firmly in charge of the Phoenician controlled region of Sicily, that is to say the western tip. Interestingly an agreement made in 509 BC between Carthage and a growing city in central Italy, Rome made this formal. The agreement outlined the zones of control and where each party could act and trade. This included what was referred to as the Carthaginian province in Sicily.

This point seems as good as any to pick up on how the different cultures on Sicily were getting along. As you might imagine the word ‘complex’ needs to be in big neon letters here. Entire papers have been written on the significance of a Greek cup found in an indigenous tomb and what it might mean. Evidence of cultural interaction is difficult, even more so when instances of it are restricted to what has survived. Even then forming a direct relationship between material from one group found in the location of another isn’t clear cut. Take for example a tomb at Sabucina, an indigenous settlement. Around 30 objects were found in this including an Etruscan basin with a non-Greek name and a bronze basic with a Greek inscription. It’s not easy to conclude which group the owner of it belonged to. Where Greek style graves are found, for example at Castiglione di Ragusa, did this mean Greeks were living there? Or were the locals copying this type of burial? What can often be found is evidence of fluidity, it’s just not clear on the exact details of the relationships involved.

There is plenty of evidence to support that people of different cultures lived together. A rather touching inscription at Castiglione di Ragusa, commemorates a man and a woman who had been buried. Where the woman’s name was Greek it seems that the man’s was local. At Naxos indigenous cups have been argued as supporting locals having moved to it and were living there.

Often the finds include Greek pottery or pieces of it, this had been imported for several centuries and is commonly found in tombs where it existed as items showcasing the wealth of the deceased. But not always. A cup from Morgantina, a local settlement, and dated to before 470 BC had I am Kupara, or I belong to Kupara inscribed on it. This isn’t unusual per se, but Kupara was a local Sicilian name, not a Greek one.

Inscriptions found across Sicily remind us that there were slightly different variations of the Greek alphabet. The indigenous Sicilians sometimes borrowed letters or structures from the Greek alphabet type used by a nearby Greek colony. Proof that the Greeks were influencing their neighbours. Some inscriptions found on shards, for example one found at Motya, may have been as the result of non-Greeks, in this case a Phoenician, practising their Greek. Indeed, fragments found at Motya from a necropolis indicate that there were Greek inscriptions there. At Motya it wasn’t just Greek, changes in Phoenician inscriptions over the course of the 6th century BC and into the 5th have been used to suggest that there was a locally evolving Phoenician language which could be called Phoenician Sicilian. Though the Phoenicians imported Greek wares it wasn’t all one way – at the Greek colony of Selinus, not far from Motya, we have amphorae with Punic stamps on them. It wasn’t just Greek pottery being traded, commercial activities went in all directions.

As for religion, and again with the caveat that there are weighty tomes written entirely on this, we can find the indigenous peoples worshipping their own deities but also new ones. At Eryx, in western Sicily the Phoenician deities of Astarte and Tanit were worshipped. It seems in the case of Tanit this was considered close to a local deity. The Greeks also imported their deities and two which seemed to have become very popular were Demeter and Persephone.

The three cultural groups, traded, loved, lost and lived alongside each other. And yet there was that buzzing of conflict about the place. It’s unclear how this dynamic was managed. The Greeks seem to have been the aggressors most of the time. This itself was borne from competition with other Greeks, the instances of tyrants and competition with Carthage and its trading networks. At the western end of Sicily, the local peoples and the Carthaginians don’t seem to have had the same issues. All of that comes with the caveat of a generalised statement and acknowledging the paucity of sources representing all groups which we have on this.

Starting at the end of the 6th century BC the background buzzing of conflict would be turned into a loud roar – but before I begin, I want to give a quick shoutout to something which you might be interested in, particularly if you are into Dungeons & Dragons. Recently I stumbled upon a post about Labyrinth & Lyre on Reddit, it’s an enhancement to the Dungeons & Dragons 5th edition basic rules. It includes aspects of ancient Greek culture and myth, with adventures, new races and loads of monsters. The creator is Jason Lira who is a long time D&D player so this comes from a love of that and ancient Greek myth and history. That’s Labyrinth & Lyre, there is a Kickstarter which has already hit the initial target. So search for it online and have a look.

Just a reminder that any ads or promos I have aren’t paid for. I don’t have a patreon or have any income streams from my podcast. When it comes to ads and promos my ethic is to share other podcasts, projects or anything I think might interest the listeners of this podcast. Just in case you were wondering.

Back then to the episode and to Gela which debuted its first tyrant around 504 BC. His name was Cleander and we don’t know much about him save that he was assassinated in 498 BC by a local called Sabyllus. The assassination didn’t lead to a return to the political norm, instead and perhaps due to the civil disruption, Cleander’s brother Hippocrates took charge as tyrant.

Hippocrates rule lasted seven years and ended, not at the blade of an assassin but in a battle against a local tribe. However, in that time Hippocrates had made a huge impact not only on Gela but most of the eastern third of Sicily. It wasn’t just the locals who fell to his ambition as he increased the dominance of Gela in the area around Gela. The Greek colonies of Naxos, Catana and Leontini were all captured and now came under his rule. At Zankle in the northeastern corner of Sicily he seems to have placed an individual called Scythes in charge. We’ll hear about him shortly.

Sticking out like a sore thumb was Syracuse and Hippocrates made a play for it. After defeating Syracusans at the Helorus river it seemed that he might have found that last piece of the puzzle. But Syracuse’s parent city, Corinth saved the day and so Hippocrates was forced to settle with a deal that gave him Camarina, a sub-colony of Syracuse, instead.

Camarina wasn’t Syracuse, but it wasn’t all that bad either. This colony was located on the southeastern corner of Sicily and so strategically it was a good platform from which Hippocrates could launch another attack on Syracuse. According to the sources he even resettled it which probably means he moved his troops there, making it a permanent base. But Hippocrates never got to make that next move as in 491 BC he was killed fighting locals.

Before I head into the next tyrant in the southeast of Sicily, I need to pick up on someone I mentioned a moment ago. Scythes – who had been placed in charge of Zankle. This was a strategically important point as it governed the crossing of the straits of Messina, a narrow channel of water between it and the toe of southern Italy. On the other side of the channel was the Greek colony of Rhegion, modern day Reggio Calabria. This was a Greek colony and boasted its own tyrant called Anaxilas. An obvious move for Anaxilas would be to take Zankle and he had a cunning plan how to achieve this.

The story goes that he made contact with Greek settlers who were on their way to Sicily and offered them the opportunity to take Zankle. This could be done easily as Scythes was out on campaign, presumably against local tribes. The new settlers were successful and when Scythes returned he found himself essentially locked out of his own city. When he appealed to Hippocrates for help Scythes didn’t get the response he hoped for. Rather that support he found himself in chains, the price of failure. Hippocrates then proceeded to do a deal with Zankle and went on his way.

As for the Greeks who had taken Zankle, their celebrations didn’t last long as Anaxilas seized Zankle from them. He then changed the name of Zankle to Messina. This after the name of the region in southwest Peloponnese which he had grown up in.

When Hippocrates died in 491 the scene was set for his sons to take over. However, the people rebelled against them. Keen to save the situation Hippocrates’ cavalry commander, Gelon, stepped forward and helped the sons crush the revolt. He then betrayed them and took power, or at least that’s how Herodotus framed the rise of Gelon. The next tyrant of Gela.

Gelon inherited a very strong position, he controlled most of the eastern third of the island. But there was the issue with Syracuse which now must have seemed even more important to capture. Lady luck smiled on Gelon in the guise of civil unrest there, it seems that the nobles and the poor were at each other’s throats. When the nobles came to him Gelon was only more than happy to help out and so in 485 BC Syracuse was added to his portfolio.

This now became his base of operations with Hieron, Gelon’s younger brother placed in charge of Gela. The only thing left to do was to ensure that there was no more unrest and Gelon cast his eyes south to the unruly sub-colony of Camarina which seems to have supported local tribes against its parent city. The solution was easy, Camarina was retaken and the people transferred to Syracuse where Gelon could keep an eye on them. This policy, of moving peoples became more common. In 483 he captured Megara Hyblaea and destroyed it. The poor were sold into slavery and the nobles moved to Syracuse.

Gelon’s main achievement or rather the event which made him famous was a battle fought in 480 BC. But this wasn’t with another Greek colony, sub-colony or even locals. It was with Carthage. The battle of Himera, as it came to be known, marked a significant change in the relations between Greeks and Carthage and just about everyone else on the island. But how exactly had it come about? We can point to earlier examples of tension between Greeks and others on the island, the failings of Dorieus for example. Yet this was more than a skirmish and to understand what caused Himera we can examine the two main accounts of it and weight them up. One account is from Herodotus, the 5th century historians and the other from Diodorus Siculus, a Greek born on Sicily and who wrote in the 1st century BC.

The two present very different accounts of what led to it all. Herodotus framed the Carthaginian involvement as almost incidental. In his account battle resulted due to conflict between Terillus, the Greek tyrant of Himera and Theron, the Greek tyrant of Acragas. Terillus had been forced out of Himera by Theron and wanted his city back. In a search for backers Terillus turned to Anaxilas who I mentioned earlier who was also his son-in-law. Anaxilas in turn suggested Carthage might be happy to support them and so a large Carthaginian force arrived. Theron in turn was backed by Gelon.

What we have here is an old fashioned falling out with Carthage simply providing muscle in a Greek Tyrant vs Greek Tyrant showdown.

Diodorus Siculus has it very different – this was much, much bigger that Sicily. His account stated that the reason behind the battle was Persia. As part of their war against the Greeks they had conspired with Carthage to attack the Greeks on Sicily. This version of events elevates the Battle of Himera as part of the wider Greeks vs Persian wars of the early 5th century. The date of the battle also links in with this. Diodorus has it occurring on the same day as Thermopylae and even Herodotus, whose narrative is less linked to Persian, has it on the date of another battle – that of Salamis. For Diodorus this continued the theme of elevating the battle to the Pan-Hellenic struggle against Persia. Herodotus’, however, may have been simply aligning dates or making an association with less emphasis.

Whatever the reasons and even to what extent that the date is accurate the outcome of the Battle of Himera was a defeat for Terillus and Carthage. Herodotus has the Carthaginian commander, Hamilcar, throwing himself on pyre he was using to make sacrifices with when he realised the outcome. Diodorus has a slightly different version of Hamilcar’s end. This one involved, you guessed it, a cunning plan which a contingent of Gelon’s cavalry sneak into Hamilcar’s camp, kills him and then set fire to the ships. Diodorus is also at great pains to underline how massive a victory this was, in fact the news of it inspired the Greeks to defeat Persia. Indeed, he even extolls it as better that what the Greeks achieved, after all the Persian king had survived along with some of his men. Whereas here the enemy leader was killed and almost all his men slaughtered.

Following the battle Carthage signed a treaty with Gelon and this included a large payment which he used to build temples to Demeter and Persephone in Syracuse. It also required that Anaxilas’ daughter to be married to Hieron, Gelon’s younger brother. The political situation had been quelled, though Gelon was keen to ensure that the outcomes further cemented his power in Syracuse. The temples to Demeter and Persephone would appease those recently brought to the city, both deities were very popular. Gelon could also point to the threat of Carthage and his position as defender of the Greeks to further justify his position to any nay sayers.

The need for justification and ensuring stability led to a grand piece of political theatre. In 479 he appeared in front of the people and essentially handed himself in, he would accept any charge levelled at him. Instead, those present acclaimed him saviour and leader. In a sense Gelon looked to repackage himself as a legitimate leader, no longer a tyrant but someone in power because those in Syracuse wanted him to be. The image of the successful leader was promoted outside of Sicily, at Olympia Gelon dedicated a large statue of Zeus and three corslets taken from the battle. Diodorus referred to something even grander, a golden tripod worth 16 talents set at Delphi. There is a debate as to what the dedications were at Delphi and whether they celebrated this victory or the establishment of Gelon in general but in any case Gelon was working to set his image in the wider Greek world.

This image didn’t last long, in 478 BC Gelon died and his younger brother Hieron took power, he was a strong advocate of the arts. Famous poets such as Bacchylides and Simonides attended his court. Even the playwright Aeschylus made an appearance and became part of a grand project, but I’ll get to that in a moment.

Where Gelon had Himera as a defining moment, Hieron had Cumae. This was a naval battle which pitted the Greeks of southern Italy against the Etruscans. Hieron sent a fleet and in 474 BC, in the bay of Naples the Battle of Cumae was fought and the Greeks were victorious. Hieron was not shy, far from it, in projecting this as a great success. Cue another dedication at Delphi and helmets from the battle sent to Olympia. In addition to this Hieron turned to the power of words in the form of Odes written by both Pindar and Bacchylides.

These Odes celebrated Hieron’s victories in the games at Delphi and Olympia, which added to his prestige. But within these odes were key messages which were equally as important.

In these works, we hear how Hieron had saved Greece from bondage and how Cumae was the equal of Salamis. They also elevated the victory at Himera, putting it in the pantheon of victories the Greeks had against the Persians.

The victory of Himera, though proclaimed, was also reshaped. Gelon, wasn’t named as a victor and instead this success of the victory was portioned to the sons of Deinomenes, namely Gelon and Hieron. It was a neat trick, Gelon’s direct association removed and reworked as a sort of family success. Elsewhere the Odes proclaimed his wisdom in rule and general awesomeness. Just take this line from Bacchylides and I quote: Hieron, you have displayed to mortals the most beautiful flowers of prosperity. Silence is no ornament for a successful man. End quote.

Hieron did face a challenge back at home. In 472 BC Theron, the co-victor at Himera died and his son, Thrasydaeus, decided to challenge him. The two forces met with Hieron victorious; peace was made with Akragas which duly exiled Thrasydaeus.

But the real achievement back home was wrapped in Hieron’s concerns about legitimising his reign and giving it credibility. This he partially achieved through the refounding of Aetna. This might sound odd, but perhaps think of it as an early form of rebranding. The old settlement of Catana was refashioned, its borders expanded and given the new name of Aetna. The original inhabitants, perhaps the poorer contingents, were moved to Leontini along with those from Naxos which was depopulated. Aetna was furnished with 5,000 Syracusans and 5,000 arrivals from the Peloponnese.

But why? Well, Diodorus gives two reasons, the first that this was a reliable source of support close to Syracuse and the other that he could be honoured as a founder. The former reason makes sense, the concern that Gelon had was that a city might turn against him. This threat still existed and so Hieron was employing a policy of control. Moving people about and mixing them destabilised a build of any possible revolt. The latter, that he was a founder needs a bit more explaining. In short, a founder of a city was given special honours, they were considered alongside heroes as deserving a cult or at least special significance. Needless to say his role as a founder was specifically mentioned in one of Pindar’s Odes about him.

Hierons employment of the arts and desire to continue the theme of founder found a new form in 475 BC, that of drama. It was this year where Aeschylus produced a play called ‘Women of Aetna’ performed at the new city. Unfortunately, it never survived but it seems to have involved a local maiden or nymph named Thaleia who was pursued by Hera after she had a liaison with Zeus and then bore twins as a result. The themes and characters seem to knit local myths and traditions with Greek sensibilities. Though we can only speculate it’s plausible that the play also pointed to the city’s foundation in some way. It would be highly unlikely for Hieron to miss a chance to make this point on the stage.

Hieron had undoubtedly continued to grow and cultivate a brand of respectability but peek a bit closer and those flowers of prosperity written by Bacchylides might also look a bit like weeds. He still had the instincts of a tyrant, the shifting of populations to mitigate rebellion, establishing Aetna as a sort of safety base nearby and no consideration given to those he forced out of their homes. Aristotle commented that Hieron had informers and spies in place keeping him informed of what was being said.

When Hieron died in 467 BC he was buried, as a founder would be, at Aetna. But he didn’t rest in peace. Those who had been forced from Aetna returned afterwards and destroyed his grave. What followed Hieronn’s death was infighting over who would take over and failures of those who did. Thrasybulus, his brother, lasted less than a year but did have that rare thing, retirement. Perhaps sensing the mood, he cut a deal to live out nicely at Locri in southern Italy. Now tyrant free Syracuse moved to a democracy, their time with tyrants was done, at least for a while.

That brings me to the end of the tyrants at Syracuse, before I finish up I’d like to briefly sum up where we are. By the time of the mid-5th century BC Sicily was a very important location for Greeks. The colonies there had developed into strong and culturally significant places, aside from the building in the southeast of Sicily there was Akragas with its temple to Zeus. This was the largest Doric temple constructed in Greece measuring 110 metres by 53 metres. For comparison the Parthenon measures 69 by 30. This period also witnessed the Greek colonies experiment with new designs, the Telamon, an architectural feature where a male figure, arms folded or upright and acting as a support, was first seen. There was also the coinage, exquisite with each colony reflecting its own symbolism. For example Akragas with the crab and Selinus the leaf. I recently posted some of these on my website so I’ll be sure to link them in the episode notes. Outside of Sicily these colonies were sending participants to the Pan-Hellenic games and winning both, at Delphi you could see the treasuries built there. These weren’t backwards colonies with potential, they were effectively city states of their own.

In the next episode I’ll be unwrapping what happened next, Carthage had been bruised but wasn’t out of the fight, there was a rebellion on the island and one of the biggest disasters in Greek military history. Oh, and another tyrant – who has terrified of getting his hair cut.

In the meantime, rate and review if you can but more importantly keep safe and stay well.