Another Halloween and another Night of the Livy Dead episode. I’ve been working on these for several years and as mentioned you can find previous episodes on any podcasting platform which you use to listen to my podcast. Keeping with the Halloween vibe here’s a recent bit on the ancient history themed pumpkins I have carved.

This year I picked a few creatures and figures from various mythologies to talk about. Here are the notes with some links and extra content including a transcription.

Night of the Livy Dead VII – roll call.

First up was the nasty character of Sulak. I also mentioned Puzazu and here’s an amulet (900-500 BC) with her face.

This may have been worn by an expectant mother or perhaps on a young child.

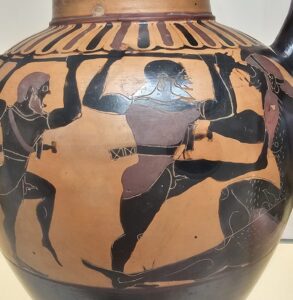

As I spoke about, Polyphemus and his fellow cyclops in the Odyssey were both a real threat to Odysseus but also represented a lot of non-Greek values. Below is a vase dating to circa 520 BC showing Odysseus’ famous solution to being stuck in a cave with him.

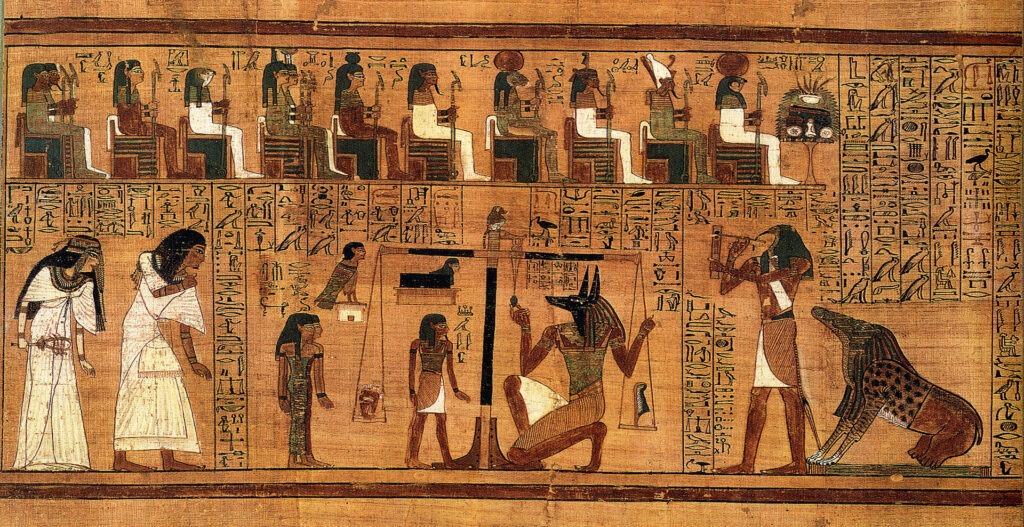

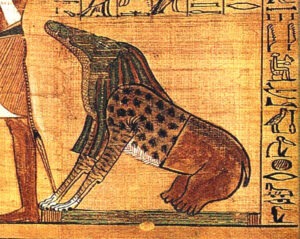

Ammit followed, on the Papyrus of Ani (circa 1250 BC) there is a scene of a soul being judged. Ammit can be seen in the bottom right hand corner.

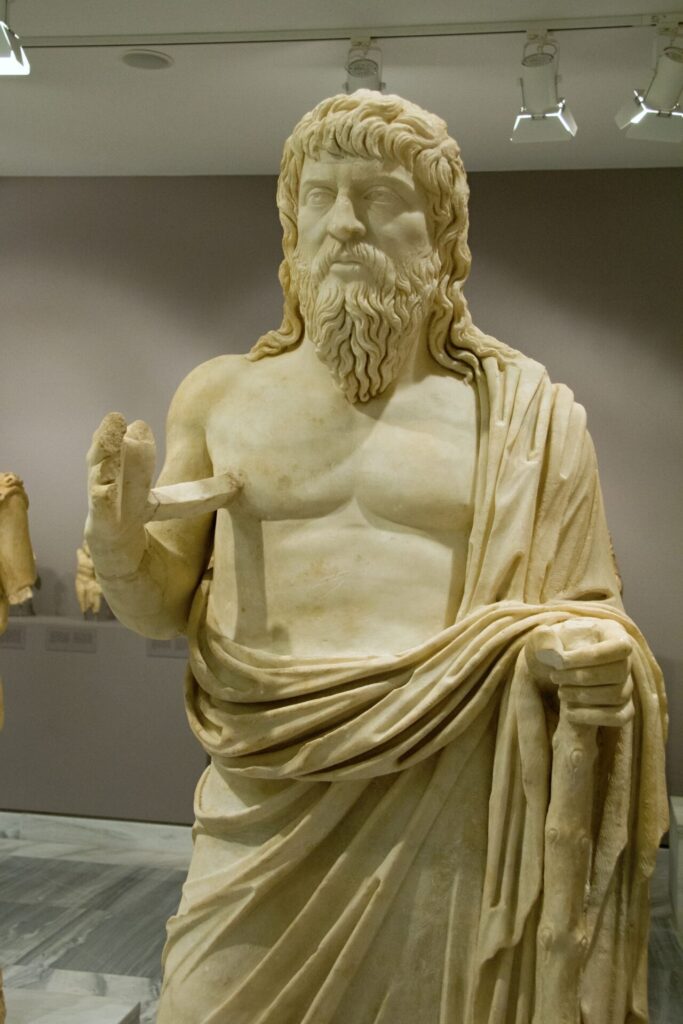

When it came to empusae and lamia – we have some references in Greek myth and an entire tale about one featuring Apollonius of Tyana (possible statue of him below). He was a 1st century AD philosopher from Cappadocia in Anatolia (modern day Turkey).

I finished with the Erinyes, here’s a wonderful 4th century BC krater with Orestes at Delphi. What is most likely an Erinyes appears above the tripod (you can make out she snakes around her).

Reading List.

Aeshylus, Eumenides.

Homer, The Odyssey.

Theoi.com – a fantastic reource for Greek myth.

Bonatz, D. The iconography of religion in the Hittite, Luwian and Aramaean Kingdoms.

Black, J & Green, A. Gods, Demons and symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia.

George, AR. On Babylonian lavatories and sewers.

Night of the Livy Dead VII – transcription.

Hi and welcome, my name’s Neil and this is the 7th Night of the Livy Dead Halloween episode where I get to examine that nice overlap between horror and ancient history. I’ve been a horror fan since I was a child, back then someone always had an older sibling who could rent a video which you’d otherwise not be able to see. This saw yours truly watching the likes of American Werewolf in London, The Shining and Poltergeist well at an age well below what was advised. The Night of the Livy Dead series has given me the chance to blend two passions, ancient history and scaring myself silly. Though it’s true that much of modern horror is just that – modern – it’s equally true that there are many horror elements or figures which manifested in antiquity. For example, the trope of the ghost rattling chains came from a story from ancient Rome.

In previous Night of the Livy Dead episodes I’ve discussed werewolves, vampires, ghosts, poltergeists, exorcisms, witchcraft and the Underworld in antiquity across Greece, Rome and Mesopotamia. And this leaves out the two-parter I did on human sacrifice.

All of these episodes are available on whicchever platform you are using to listen to this one – just have a scroll down. You may even find something else you want to listen to.

Before we go any further, you can find episode notes on my website – ancientblogger.com and this will include links, a reading list, transcription and other content which I hope is useful. You can rate and review this episode on numerous platforms, so please do and thanks for the reviews I have been getting. It’s not just about getting the word out and making the magic algorithms work, it can be a real pick me up and certainly brightens my dad when I hear from you and you have something positive to say.

If you want to say hi or find more content I’m on YouTube, instagram, TikTok and X as ancientblogger, with this podcast as @houndancient on X as well. You can also email me [email protected].

What I have done in this shorter episode is to pick some figures or creatures from across Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece and Rome which fit well within the horror genre or at least have something of the scary about them.

My first selection definitely fits this definition. Not by virtue of what they were, although it’s still scary, but where and when they manifested. A confession I feel comfortable in making is that night time trips to the toilet still spook me. No idea why but it seems to be the moment where my brain delights in flicking through a back catalogue of moments in horror films which I’ve watched. Be it the tapping of fingernails by a floating sibling outside the window – the original Salem’s Lot still terrifies me – through to twin girls holding hands or just a single red balloon. I say to myself that I don’t turn the light on in the toilet because it’ll hurt my eyes and wake me up a bit but really it’s because I’m worried what I might see behind me if I look in the mirror.

Though the ancient Mesopotamians hadn’t had the pleasure of hours in front of a screen peeping through fingers they too might waver at the prospect of a night time trip when nature came calling because there was a demon to be avoided in such an instance and it resided in what can be roughly described as the toilet.

I covered demons and exorcisms in Mesopotamia in a previous episode and if you listened to this you’ll know that demons were both numerous and weren’t restricted to night time hours. They were also not automatically bad things, the best definition I read which I used in the episode was that they were agents of chaos. Sometimes useful, sometimes not and generally best avoided. In fact you’ll hear a bit about how they might be useful shortly.

A chief way which a demon might cause a bad outcome for a human was through manifesting an illness in their victim. But fortunately there was a tradition of exorcists in Mesopotamia who might be able to diagnose the demon in question through the illness or condition its victim was experiencing. In short you could work out which demon it was through the symptoms presented by their victim.

The demon in question here was one named Sulak. In art he was depicted as a lion standing on its hind legs. As if a lion in the toilet couldn’t be made any more scary.

On the subject of where Sulak could be found, the toilet, I need to clarify that this is a loose description. For many the fields may have been the likely place to visit but some houses had a room with a drain and this served as a sort of toilet. Either business was done there or chamber pots emptied there. An activity mentioned there also was washing, probably of the hands and anything else which needed it. Sulak was a real concern, so much so that on the 6th and 7th days of the month of Tashritu, which was an autumnal month, it was advised to avoid the toilet room completely.

As mentioned demons might manifest in an illness, condition or disease. What became linked to Saluka as diagnosed by an exorcist was something called simmatu, or paralysis. On one cuneiform tablet gave a diagnosis that if a mans eyes, neck and lips are affected by simmatu, then Sulak was responsible. Another symptom associated with the demon was the left hand side of the body hanging limp. What seems to be described is some form of a stroke.

Though this might seem quite a random set of circumstances there may be a kernel of truth which links these elements together. There is a type of stroke called a subarachnoid haemorrhage. These can occur through straining, be it lifting something through to coughing. But also straining whilst, well, you can can work that out.

What may have been the case was that the people of Mesopotamia made a connection between those who suffered a type of stroke and having been in the toilet recently. It’s also possible that it was a result of other types of strokes but given that most people make daily trips to the toilet you can imagine how it could still be linked, even if the stroke had nothing to do that particular thing.

In terms of preventing Sulak this was done in a common method to dissuade a demon, that is using clay figurines of an appropriate entity who will keep Sulak away. In this instance it was the lion centaur which was apparently able to chase or at least keep Sulak away. Often a particular demon could be nullified by another and this gives me a neat segue into a another Mesopotamian demon who made it to the big screen. Pazuzu. In the film Exorcist, unusually one I didn’t see whilst still a child, the demon who possesses the child Regan is identified as Pazuzu.

However, Pazuzu wasn’t that bad of a demon, certainly miscast because it was often appealed to to protect pregnant women and women in childbirth from a very nasty demon called Lamastu who predated on newborns and women in childbirth. Amulets and figurines of Pazuzu have been found and it’s probable that these were used by those in need of keeping Lamashtu at bay. Perhaps on the bed or attached to the woman when she was giving birth.

Next up is someone, or something I reckon you will have heard of. In fact they are a staple of Greek mythology – the cyclops.

It’s Hesiod, writing in the 8th century BC, who describes them as named after their single orb-eye and very strong, but they were also known for their craftsmanship and skill. They fashioned thunderbolts for Zeus and were associated with building walls. However, they were not all the same and one which Odysseus encountered was very much the stuff of nightmares.

In the Odyssey the cyclops are described in dire terms and in many ways different to the sense offered by Hesiod, namely a skilled and obedient bunch. The caveat here is that Odysseus is describing his encounter with them to a king and given how he behaved perhaps this picture of them benefitted him given the outcome. But that aside I’ll describe why the cyclops were a truly awful lot, or at least they were according to Odysseus. To start with they were a lawless bunch and layabouts as well, they didn’t farm or do much of anything and even worse they had no social or political structure. In addition to this they didn’t show any deference to the gods.

For a Greek listening to this, particularly in the Classical Period this setup was the antithesis of their beliefs. The cyclops, it seems, were less hippeis and more hippies, apologies for the niche joke there. What made for a civilised society in ancient Greece were norms such as a structured and ordered society and what is described here is everything but. We can pursue the theme of the uncivilised further, when Odysseus enters the cave of Polyphemus, the cyclops in question, he brings gifts and appeals to an essential moral standard in ancient Greece, that of xenia. This was an epithet of Zeus and related to being a good guest and equally a good host, it’s a theme which bobs along in the narrative of the Odyssey. After all the great crime of the suitors at Ithaca was largely funded by their bad behaviour as guests.

The response which Polyphemus gave would have shocked any Greeks listening to it. He rebukes this notion and even goes further to dismissing the Gods, stating that the cyclops were stronger so they could just ignore them. These highly contentious words are matched with equal barbarism as his next action is to snatch a couple of Odysseus’ men and make a snack of them. There’s even an extra layer of the barbaric here, they aren’t even cooked. That’s not me being faecitious, it’s another detail of just how uncivilised the cylops are – they don’t seem to cook their food.

And this detail tracks across to how Odysseus in part deals with Polyphemus. When Odysseus set out on the island he took with him some very strong wine in a goatskin. Wine in ancient Greece was cut with water, it was considered barbaric to drink it neat. But that’s how Polyphemus quaffs the wine given to him by Odysseus. Uncooked meat and uncut wine, just as well tripadvisor wasn’t around back then.

Polyphemus is a terrifying individual in more ways than one. Simply put he’s a large monster who is out of control, despite being a son of Poseidon he has no regard for the gods, and in fact you can add that to the list of social conventions he breaks, that is to day lack of deference to your father.

But outside of this the world he inhabits is equally as troublesome. Where is the structure both politically and socially? The description of the land of the cyclops is that of abundance, in short here’s the dream of any Greek – to have that agricultural resource to work. Yet the cyclops barely lift a finger and worse than that they reject anything which might bring this about.

The sujbect of rejection brings me to another deity, a goddess who certainly had this in her locker. It’s time for me to talk about the Egyptian deity Ammit.

One of the things ancient Egypt is famous for is its mummies and therefore its treatment of the dead. It’s understandable, but this aspect does receive a lot of attention and it’s easy to forget that ancient Egyptians weren’t a bunch of emo or goth kids thinking about how it all ended. They were a vibrant people who were tuned in very much to be business of being alive and enjoying it.

But of course there are the mummies I mentioned, those tombs and the intricate path the soul took into the underworld. There are of course different versions but a generalised picture has the soul of the deceased judged in a number of ways. One of the judgements involved the heart of the soul being weighed. The Egyptians seemed to consider the heart as something which recorded all the acts of that person. If they had acted badly it would be heavier for those acts and it was placed on a set of scales and weighed against a feather which represented virtue. If the heart was lighter or the same as the feather then the soul could progress to the next stage of its journey. If not, well, that’s where Ammit or Ammut came into the equation. Known as the devourer she took the form of a creature with the head of a crocodile, body of a lion and hindquarters of a hippo. The heart of the soul would be tossed to her to eat and with that act the soul would die a second death. That was it, nothing left but oblivion.

This event was the worst of all worst case scenarios for an Egyptian. It made sense that the being or entity responsible for such an act would have such a fearsome visage. The crocodile, lion and hippo were apex creatures which no mortal wanted to tangle with. In the form of Ammit there were all three there.

So far I’ve listed creature who would scare you outright. But what about a creature who could appear attractive. For the Greeks and the Romans there were such beings but with a bit of an overlap and again it’s important to remember that there wasn’t a formal cannon here.

In the 6th century BC there was a female poet called Erinna, we don’t know much about here and in fact it’s been disputed that she could have lived a few centuries later. But in any case she wrote a poem called the Distaff which sadly only survives in fragments. One fragment recalls the terrifying prospect of Mormo, a creature which scared her and her friends as children. It walked on 4 legs and had huge ears but perhaps it’s most intriguingly was a shapeshifter, it’s face could change and here we meet a characteristic you’ll hear a bit more about. That is to say shapeshifting.

Mormo translates as ‘terrible one’ and you can commend the branding there. Less so with the next Greek shapeshifter, the Empousa. This translates as ‘Moves on one leg’ which doesn’t exactly strike you with fear. One plausible reason that the empousa was so named was because it had one leg made of copper or bronze, at least that’s how it’s described in Aristophanes’ comedy, The Frogs. Here the Empousa is described as changing forms from different animals and even to a beautiful girl. Yet it still possessed a copper, or sometimes bronze, leg. It could also be the leg of a donkey and ‘donkey-footed’ was a nickname for an Empousa and I say ‘an’ as it seems that the Empousa was the name of a general type of monster.

Before I go further it’s worth noting that the idea of a creature with shapeshifting abilities and a leg which seemed out of sorts wasn’t restricted to Greece, or even Europe. In south America there was the Patasola, myths of it varied but they boiled down to a similar description of a shapeshifting creature who would assume the form of a beautiful woman, upon seducing its victim it would then reveal it’s true form which included a single leg. The La Tunda was a variation of this, the difference being it always had a wooden leg, even in the form of a beautiful woman.

For Rome, never one to miss out on a good idea, there was the Lamia. Again this was a shapeshifter who assumed the form of a beautiful woman to seduce young men and eat them. A tale is recounted of a famous Lamia which hung around the Greek city of Corinth and was defeated by Apollonius of Tyana who lived in the 1st century AD.

So it goes that a young man called Menippus had come under its spell and agreed to be married to a mysterious rich Phoenician woman. At the sumptious wedding breakfast Apollonius and the bride to be clashed, with Apollonius countering what was essentially a giant mirage with his wise words. After questioning the mysterious woman she admitted that she was an empousa – though I should add there is conflation here with her being a lamia – and her goal had to be to fatten Menippus up before feeding on him.

Given their proclivity for eating people, however this took place, the lamia and empousa are sometimes cited as a sort of proto vampire. The danger with this is that it ignores the fact that our modern interpretation of the vampire is largely formed around the work of Bram Stoker. The good count wasn’t the definitive vampire, he was one version of many undead or supernatural creatures who were said to feed on humans. Possibly the most famous version but far from the only one.

For our final set of creatures I turn to Greece and here we meet another group which found fame, or infamy in literature – or rather a Tragic play. They were concerned with vengeance, would continually track down their victim and would drive their victim mad. They were the Greek Erinyes, sometimes known as the Furies.

Their birth is recorded by Hesiod in his Theogony and it seems somewhat appropriate given their nature. When Cronus, the father of Zeus, castrated his father the drops of blood which resulted formed the erinyes. Theirs was a brutal introduction into the world and the fact that it was borne from an act of violence to a parent is ironic given their remit – as agents of vengeance for the most serious crimes, one of which, parenticide formed arguably their most famous myth.

Their name is argued as originating from ‘I hunt up or persecute’ and there were three of them, Tisiphone, Megaira and Alecto. These names translate as ‘murder retribution’, ‘grudge’ and ‘unceasing’ respectively. Perhaps their most famous appearance in myth was where they chased Orestes for the act of killing his mother, Clytemnestra. The Greek playwright Aeschylus wrote a play about this, the Eumenides, the final of three plays which formed a trilogy known as the Orestai. Roughly speaking this followed the tale of Agamemnon when he returned from Troy who was murdered by his wife Clytemnestra who is then murdered by her son Orestes.

Eumenides translates along the lines of ‘the friendly ones’ and this referred to the erinyes. So why the change in name and why choose a name which feels wholly inappropriate? Well, it’s likely that this was due to a combination of fear and respect for them. Plays were performed within a religious context and so perhaps this was done as a way of appeasing them or rather just not invoking them.

In the Eumenides Orestes is hounded by them until he finds himself at Athens where he is judged for his crime. It’s a dramatic story which dealt with many issues, one of which was the nature of justice and what form it might take in a modern Greek city. As mentioned in the episode on Democracy a great point made by Professor Edith Hall was that Tragedy encouraged debate, it made people ask questions and this was something the newish democracy needed its citizens to be able to do or at least get them used to being able to do.

It’s in this play that we find the earliest descriptions of the erinyes. Aeschylus describes them as dressed in black and entwined in snakes. This description of them was to stick, though Pausanias, a later Greek writer commented that the snakish aspect to them was something invented by Aeschylus. They were certainly considered terrifying in real life, there were anecdotes about how audience members fainted when they appeared on stage.

In Greek art the erinyes appeared often as normal women, albeit with snakes about their person and though this might seem at odds with their fearful countenance it makes sense once you consider it. For a start Greek art, and by this I predominantly mean Greek vase painting, placed an importance on the narrative – telling a story. For this to work you need those involved to be identifiable, hence the snakes as an identifier for the erinyes. Incredibly skilled though they were the description of the erinyes as figures in black shrouds didn’t exactly lend itself to an easy repesentation on a vase.

For the ancient Greeks the erinyes were fearful creatures because of how they looked, how the might drive you to madness but also their context. As mentioned the erinyes sought vengeance for heinous crimes, the sort which were an affront to the most fundemental Greek values.

And on that we have reached the end of the episode. I hope you’ve enjoyed it and please get in touch to tell me what you think – as with any list I am sure I have missed out a couple of options but I can always cover them another time. And until next time keep safe, have a great Halloween whatever you are doing, and keep safe.