I hope the below helps with giving more context to the episode on Hannibal and his exploits from the highs of Cannae through to the lows of Zama. In the episode I mentioned previous episodes I have done on Hannibal and his battles (and much more). Here are some links to them.

Hannibal in Spain.

This is about how Hannibal developed as a general as well as why Carthage was in the Iberian peninsula.

Trebia.

Trasimene.

Cannae.

Magna Graecia.

This episode covered southern Italy and I mentioned it in the episode a few times.

Spolia Opima.

I mentioned this in the episode – the general rule was that if a general killed the enemy King or commander or king in battle and stripped the armour from him he could claim this. It was a very niche achievement. Not only did you have to kill the enemy general or king, you yourself had to be leading the army.

Marcellus had achieved this in 222 BC at The Battle of Clastidium. In the episode I mentioned Cossus and Romulus, the two other people to have achieved this. You can hear more about Cossus and how it all went down in a couple of episodes of the Partial Historians podcast (episodes 129 & 130).

Images.

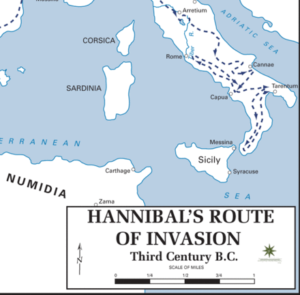

Firstly, here’s a map which gives an outline of Hannibal’s movements in southern Italy.

Here’s the troop deployment at the Battle of the Metaurus. It’s been inverted (the river would be at the top of the map) – nice work.

A very detailed map with the routes taken into Italy by both Hannibal and Hasdrubal (with battles and locations). You can see Metaurus is quite far north.

Here’s Carthage and the nearby cities, including Hadrumentum (where Hannibal marched from). The location of Zama is debated, but it’s thought to have been to the west of Carthage.

The remains of the Temple to Hera at modern day Capo Colonna in southern Italy. What a beautiful view.

Reading list / sources used.

Livy. History of Rome.

Polybius. Histories

Goldsworthy, A. The Fall of Carthage.

Lancel, S. Hannibal.

McCall, J. The Sword of Rome a biography of Marcus Claudius Marcellus.

Shean, J. Hannibal’s Mules: The Logistical Limitations of Hannibal’s Army and the Battle of Cannae, 216 B.C

Transcription.

As ever there may have been some slight deviations on the day but this should match well enough.

Hi and welcome, my name’s Neil and in this episode I’m continuing on from a previous set of episodes which each featured Hannibal. These centred on a specific battle, the three famous ones in which he defeated Rome. But they are actually a bit more than that if I do say so myself. Each went into the lead up, the characters involved and the events during and after the battle. You don’t have to have listened to them for this to make sense but it might be good to indulge in a bit of binge listening if you haven’t.

What I’ll be unwrapping in this episode then is what happened after the famous battle of Cannae in 216 BC. In short Hannibal campaigned in southern Italy where he met success and setback. These ultimately resulted in him needing to travel back to Carthage and fight Rome at Zama.

Before I start just a few points. Firstly thanks for the nice emails and reviews, keep them coming! I keep saying it and I will keep saying it but I don’t have a patreon or a marketing budget. If you can spare the time to rate and review wherever you listened to this it makes a huge difference.

Episode notes are on my website, ancientblogger.com. These will feature a transcription, maps, a reading list of the sources I have used, images and anything I think might be useful for you. My website is also a website in itself, I’ve been updating and improving it of late. It’s all ancient history so check it out anyway.

Elsewhere I’m on instagram, threads, youtube, tiktok and tiwtter as @ancientblogger. This podcast also has its own twitter handle of @houndancient. If you are feeling old school and want to email me – it’s [email protected].

All dates are BC unless otherwise stated. I usually say BC, but just in case I don’t then assume it is. Ok, let’s get started.

In August of 216 BC Hannibal had inflicted upon Rome its greatest defeat. Noted by military historians as a near perfect victory Hannibal had taken on a large Roman force and within a few hours reduced a battle to a work of butchery. However, this victory came with expectations and Livy painted a scene where Hannibal’s cavalry commander, Maharbal pressed for Hannibal to march on Rome. Hannibal declined and this caused Maharbal to issue the famous response:

“Hannibal, you know how to gain a victory, but not how to use one”.

Whether this was ever said is debatable. It’s a critcism which belongs far more to an armchair general, or rather a later Roman historian, than a cavalry commander who well understood the reasons why a march on Rome was implausible . However, for the sake of argument and also because it has become a famous criticism of Hannibal, it’s worth weighing it up.

To start with consider the distance, Rome was 250 miles away and this meant that there was no prospect of surprise. As Livy himself noted the city found out soon and immediately strengthened the defences there. Now assume that Hannibal’s army was fresh and not exhausted and in need of a good few days rest it would take a while to reach Rome.

One paper I’ve included in the reading list by John Shean goes into the logistics of moving Hannibal’s forces that distance and keeping it fed. The numbers are truly eye watering. Using the his numbers and estimates Hannibal’s army after Cannae would require around 286,000 pounds of food a day, that’s around 130,000 kilograms. And that’s without considering water.

But let’s assume Hannibal magically had all the supplies he needed. Shean estimated it would take at least 19 days continual march to get to Rome and the supply chain would require just over half a million animals.

But again, using magic let’s just drop Hannibal’s army right next to Rome. Well, here we’d have a problem, in regards to conducting a siege. Hannibal lacked both the equipment and the expertise to conduct a long siege. Before he’d laid foot in Italy he’d besieged Saguntum in Iberia, this had taken many months and it had been very costly. And of course what about his army? Many of these soldiers, and I’m looking at the Celts here in particular, had joined up for glory and to win battles. They weren’t going to stick around for months doing nothing. And finally any army conducting a siege was very vulnerable from attacks. It’s actually difficult to find one reason why Hannibal would have marched on Rome. Though later, as you’ll hear, he comes very close to it.

Cannae had been fought in the south of Italy and Hannibal seems to have had plans for this region of the Italian peninsula. It’s important to consider that this region didn’t have deep roots with Rome.

In fact Rome had only started engaging there earlier that century and had only secured its influence in 272 BC when it took Taras or Tarentum.

This was a region which became known as Magna Graecia, ‘Greater Greece’ because of the Greek colonies which had grown there. I covered this in an episode titled Magna Graecia: Greeks in Southern Italy and discussed how Rome ended up securing the area. Anyway, my point here is that this part of Italy wasn’t some securely held Roman territory with a historic relationship imbued with loyalty. There were plenty of cities who would happily take their independence back if given the opportunity. One such location, Tarentum, had even come out for Hannibal after his victory at Cannae even though it had a Roman garisson.

Hannibal’s first movements after Canne took him west and to Campania and this was somewhere he’d visited in 217 after the victory at Trasimene. Back then it was a big logistical shop, Hannibal helping himself to the harvests there. Back then he’d also been tracked by Fabius Maximus and almost trapped in the region. But this time there was no such Roman force on his heels. His main aim seems to have been to take Neapolis, or modern day Naples. This would provide him with a good harbour, something he’d not had the chance of yet. However, the defences of Neapolis put him off – this further underlines how he was never going to try and take Rome. But he didn’t leave empty handed. If he couldn’t take Neapolis there were other cities he could try.

And that’s what happened. Nearby Capua fell to him, but not through a siege, instead good old fashioned treachery. Or at least treachery if you were a Roman.

According to Livy the city was betrayed to the Romans by a faction within it. This was more common than you might think, often a city had a faction, usually by this I mean some disgruntled nobles who had been sidelined and realised a change of owner would be good for them. Livy added some gruesome details to enhance the horror of it all, for example some Roman officials locked up in the steam rooms of the baths and cooked to death. Perhaps that’s a tad fanciful but it wasn’t exactly a bloodless event.

Signs were positive for Hannibal and pardon the pun things were cooking nicely. However, it was here he was to meet a Roman general who would be a continual thorn in his side, Marcus Claudius Marcellus.

Marcellus was no green general like some others which Hannibal had faced. Here was an individual who had excelled as a soldier and as a general had defeated an army of Gauls in 222 BC. He hadn’t just defeated them, in the battle he killed the Gallic King and won the spolia opima. A general killing the enemy commander was a rare thing, indeed only two figures had done this previously. Given one was the mythical Romulus and the other Cossus, a 5th century general this was quite something. Just as an aside there’s a whole thing about how Cossus achieved that great feat on an episode, in fact two episodes by the Partial Historians. But aside from that Marcellus seems to have been a genuinely capable general, much to the chagraine of Hannibal.

Hannibal’s first experience of this was at Nola, to the east of Neapolis and south of Capua. Hannibal had taken Nuceria and was presumably looking to increase his hold on the area. However, when camping outside Nola he seems to have adopted a lax attitude, or it was simply an off day because Marcellus led a sortie from the city and surprised the Carthaginians. The result wasn’t a victory exactly but it was enough for Hannibal to move his forces away and returned to Capua where he spent the winter.

In 215 Hannibal turned his attention further south. Bruttium is a region which roughly equates with modern day Calabria. If you imagine the foot of Italy this forms the mid-foot to the tips of its toe. Most of this was pacified for him by Himlico, that is all apart from Rhegion which is a city right on the tip of that toe. This activity hadn’t gone unnoticed, given the close proximity to it the city state of Syracuse on Sicily saw an opportunity and allied with Hannibal.

He was also able to realise the dream of being supplied by Carthage and at Locri a force arrived which even included some elephants.

With these elephants and perhaps the boost to morale Hannibal tried once more to take Nola but again was met by Marcellus who drove him away. Hannibal’s response was to send some of his army to Bruttium whilst he moved east to Apulia, again, to use the foot metaphor this is the heel region.

By 212 BC things had changed for the worse and Hannibal’s campaign started to stagnate with some gains lost. Rome hadn’t been pleased by Syracuse’s alliance and had sent a force there under Appius Claudius and Marcellus to take it. This they did and it was this event in which Archimedes, the famous mathmetician and all round genius was accidentally killed. With Syracuse now lost the position Carthage had on Sicily would be far weaker. But it wasn’t just here where Rome was looking to take back ground. Capua still stood out as Hannibal’s main gain in Campania and Rome was putting pressure on it.

On the southern coast of Italy Hannibal did have some luck and took the city of Tarentum, earlier known as Taras. I spoke about this city a fair amount in my episode on Magna Graecia. Originally a Spartan colony it had fulfilled its potential and became a leading city in southern Italy. It’s fair to say that Tarentum had a very strained relationship with Rome. It had employed Pyrrhus against Rome in the early 3rd century which ultimately led to its defeat. When Rome finally took the city in 272 BC it established Roman dominance in the southern part of Italy.

Rome’s dominance of this area was therefore still relatively fresh. And given that Tarentum had been its long standing opponent here there’s little surprise that Tarentum would wish to become independent once more. As mentioned, it had been the leading city of the region so perhaps here was a chance to reset things to how they had once been.

The tale behind the taking of Tarentum is suitably dramatic. Hannibal received 13 young men from Tarentum at his nearby camp. Successive visits outlined the plan and what would happen. As with Capua once the city was taken it would operate as was and wasn’t required to contribute anything, though any Roman property would be fair game.

And game is the word here. Pivotal to this plan was a hunter Philemenos. He was already well known at Tarentum and started going out often at night. When he returned he’d invariably bring something nice and edible to the soldiers posted at one of the gates. Eventually he built up a rapport which saw these gates opened to him at the sound of his whistle when he was approaching. You can probably guess where this is going.

Hannibal moved a force over several days near to Tarentum. Done this way it wouldn’t arouse that much suspicion and a screening force of Numidian riders gave the impression of a simply foraging party. Nothing to see here.

The plan took place whilst festivities in full flow one evening, this ensured that the governor would be distracted and they would know where he was, that is to say in the town centre enjoying them. The conspirators inside the town gave a signal at which point the soldiers at one gate were killed and the gate opened.

At a different gate Philomenos approached with a few colleagues and some nice boars. He whistled and the soldiers there opened the gate expecting some choice cuts. Cuts there certainly were but made on them by a small force hiding nearby. Hannibal now had access to Tarentum from two points and he moved his men to the market square where they took control of the city, albeit apart from a few Romans who had made it to the citadel and holed up there. Despite his attempts to get them out he couldn’t though at this point there was no great threat from them.

Hannibal wasn’t able to enjoy the success of taking Tarentum because news reached him that Capua was being besieged. Capua was a strategically important location and even beyond that Hannibal couldn’t afford the dent in his PR that losing Capua would make. As with his exploits in northern Italy he had eyes on him, loyalty could only be demanded from a position of power and if he was to sway any more cities to his side he needed to demonstrate that he was still a viable option. In the spring of 211 BC he moved out with a lightly provisioned and equipped force which could move quickly to Capua.

Once he reached Capua Hannibal was met with a scenario he wouldn’t ever have chosen. Hannibal’s successes had relied on feints, surprise and mobility. His infantry holding the line whilst his cavalry flanked and caused chaos. What he had always lacked was a large number of heavier infantry and this was exaclty what was needed. The Roman force laying siege to Capua weren’t about to budge or put themselves in a vulnerable position. They were set defensively – if you wanted to fight them this would take the form of a slug fest and Hannibal didn’t have the forces for this.

But what he did have was his ability to trap and coax a general into a silly decision and this is what he tried to do here. According to Livy he wrote a letter to Capua stating that they didn’t need to worry as he was going to march on Rome, and he ensured that this was intercepted. Hannibal then struck out for Rome, the intention being that it would cause panic and the forces at Capua would move away. When Hannibal appeared near Rome it caused panic in the city and an army was mustered to meet him there. It’s not clear if this was formed of the men from Capua or fresh recruits though a force under the Roman proconsul Flaccus did leave Capua to chase down Hannibal.

Outside of Rome the two armies were about to clash, but fate intervened in the form of a violent storm which prevented any fighting. There was action back at Capua, ironically the letter Hannibal had wanted intercepted could have done with actually making it there. Those in Capua thought he had deserted them and the city surrendered to Rome.

The following years saw more Carthaginian losses in terms of cities or towns going back over to Rome. Worse was to come in 209 BC when Rome laid siege to Tarentum which included that small Roman force holed up in the citadel there. At this point Hannibal was in Bruttium and Rome well understood that in order to take Tarentum he needed to be prevented from reaching it. This job was given to an old enemy of Hannibal, Marcellus. So began a game of cat and mouse with Marcellus keeping close to the Carthaginian army as it made it’s way to Tarentum.

At Canusium Marcellus finally caught up with Hannibal but was soundly defeated, this didn’t unnerve him and the next day he sought to balance things out. Again battle was joined but this time it was Marcellus who was victorious or so Livy tells us. It’s debated whether the second battle ever happened and reasons for this are that it reads as just a bit too boys-own. By that I mean that it’s crammed with cliches including a last minute save by the Roman line driving the elephants back. In narrative terms it also balances out the defeat the day prior, a great comeback. But perhaps the main indicator that it may have been fabricated was the outcome. Hannibal, though apparently soundly defeated, was able to move his army to Bruttium. Tarentum now a lost cause. Compare this then with the supposed victor, Marcellus. His army was unable to move for several days due to casualties. This doesn’t quite add up.

In the summer of 208 BC Marcellus was again to clash with Hannibal, at this point he was again a consul, his 5th time as one in fact. He was joined by the other consul Titus Quinticus Crispinus. Two consuls and their armies now hunted for Hannibal in southern Italy and in the summer of 208 BC they met near the border of Apulia and Lucania near a place called Venusia.

It was to be Marcellus’ last battle, although the battle never fully took place. Prior to it the two consuls decided to take a small scouting party to make observations and this was intercepted by a unit of Numidian cavalry which Hannibal had placed in a wooded area nearby. Whether this was intended to launch an attack during the upcoming battle or simply anything which came near to it is unknown. Marcellus was killed and Crispinus was severely injured, he died a few months later and Livy noted that Rome had never lost two consuls in the same year.

Given that one consul was out of action and the other dead no engagement between Rome and Hannibal took place. Taking advantage of the situation Hannibal moved to Locri in Bruttium where he spent the winter. Back at Rome the situation with the consuls was remedied with the election of a dictator. This was a political safeguard and not to be confused with how the role was skewed by later individuals at Rome. A Dictator was specific to a set of conditions, in fact one dictator had been Fabius Maximus who had looked to check Hannibal after Trasimene.

The man chosen as dictator was Titus Manlius Torquatus, by this time in his 70s and a very experienced Roman politician. Chief amongst his duties was to oversee the consular election which occurred midwinter. The successful candadidates at this point in Rome’s history would then take begin their consulship in the following March. In this instance the two elected were, Gaius Claudius Nero and Marcus Livius. Nero had been involved at Capua during the seige and had spent some time in Iberia, as such he had a good military understanding of the situation and of who he was facing.

Marcus Livius was an odd choice, mainly because he had been in the political wilderness ever since his conulship in 219 when he was prosecuted for financial irregularities. Given the nature of Roman politics this really said something.

The main objective in 207 for the consuls wasn’t just Hannibal. In fact Hannibal was relatively well contained, the bigger problem was his brother, Hasdrubal. Spies from Massilia, modern day Marseille, had reported back that he was in possession of a large army and would be crossing the Alps. The consuls were given separate spheres of operation which was a relatively new thing. Nero would keep Hannibal in the south busy, or at least distracted. It would be Livius who would move north to intercept the new Carthaginian force whose sole mission would be to move south and link up with Hannibal.

Livius’ first challenge was assembling a strong army, or at least one which could put up a fight. This wasn’t a problem for Nero who was able to use the experienced units stationed in the south and who had been in regular action. Perhaps underlining the problems he faced Livius was forced to hire slaves into the army. And here we meet a problem which had finally started to hit Rome, manpower. Rome wasn’t just fighting in Italy, it had forces in Spain. A census taken in 287 BC had the numbers of citizen Romans hovering around the 177,000 mark, a more recent one gave the figure at 137,000. This included men too old for service and those who wouldn’t pass muster but even with a pinch of salt these numbers give some indication that the war effort was starting to bite.

Hasdrubal’s movement across the Alps and through northern Italy was far, far easier than his brother’s had been. The Celtic tribes seemed happy enough for another Carthaginian force to head south and kill Romans, always an easy vote winner with them. Soon Rome felt the presence of Hasdrubal, Placentia – modern day Piacenza- was at that time the most northern of Rome’s strongholds.

Hasdrubal spent a short time trying to lay siege to it, but failed. He then sent a letter to Hannibal indicating that the two were to meet in Umbria, a region in central Italy. But this letter never made it to Hannibal, the riders took the wrong road and ended up near Tarentum where they were caught and the letter taken to Nero.

Nero realised the situation and informed the Senate that he was abandoning his positon in the south and heading north. As well as disobeying his orders there was a practical problem in hand. Nero well understood that if he decamped and moved his full army north it would likely result in two outcomes. The first was that Hannibal would now be free to undo Roman gains there. Secondly and possibly the real danger – Hannibal would have realised something was up. He’d then track Nero’s army and either harass or wait till the right time to attack it. Probably an ambush of some sort.

In a stroke of ingenuity Nero took a leaf out of Hannibal’s book and combined movement and deception. This didn’t require a large force, so he left the majority of his army in southern Italy and took a picked force of 1,000 cavalry and 6,000 infantry. This smaller number could move more quickly and wouldn’t necessarily alert Hannibal that he was up to much. Even so Nero embraced the aforementioned art of deception. He made a bee line for a Lucanian town with a Carthaginian garisson. It would therefore seem as if Nero was merely launching a small assault. However, at night he undertook forced marches to move north quickly. Eventually he arrived at Picenum, a region in the eastern central part of Italy and close to where Livius had his camp. Remember that the orders Livius had were to intercept Hasdrubal and defeat him,

We can only speculate if Hannibal ever realised anything. Even if he did there was still the majority of Nero’s army in the south which would have made things very different for him if he’d tried to follow. In any case the chief objective of Nero’s, to get to Livius with a sizeable contingent of men, had worked. When he arrived at Livius’ camp Nero did so with as little fuss as possible, the idea still being to surprise Hasdrubal.

Though the ruse might have initially worked Hasdrubal soon understood that there was another consul in the Roman camp to the south of his camp. You can only imagine the despairing conclusions which tumbled from this. First that he was now facing a much larger army than he had previously been expecting. Estimates for the numbers here range, but it’s assumed that both Hasdrubal and Livius had around 30,000 troops each. Hasdrubal couldn’t know how many more he was facing. He just knew that now he was now outnumbered.

Second was about what wasn’t there, namely his brother. Was he dead, or had he been defeated on the way? Worse still did he even know about any of this? The sorry realisation must have been that this wasn’t a coincidence, that his letter had been intercepted and read.

What Hasdrubal now experienced was the stuff of nightmares for any general of any period. And that’s because decisions were made, as they are now, on information. It’s one of the enduring strategies of war, to try and trick the enemy. Let them understimate your numbers, let them overestimate your numbers. Presumably Hasdrubal had a battle plan based on what he knew. All this had now changed.

With this is mind he did the sensible thing, striking camp he moved along the south bank of the river Metaurus, today known as the Metauro. It runs from the Appenines and travels 110 km (68 miles) east to the Adriatic sea. Hasdrubal’s new plan was to cross it and move back north, perhaps to Gaul or amongst a friendly tribe of Celts in the north of Italy. The problem he had was finding that place to cross, Livy painted a pitiful scene in which Hasdrubal’s scouts abandoned him and this left him trying desperately to find a fording point which didn’t exist.

Failing to find anywhere to cross the Romans caught up with him and in 207 BC the Battle of the Metaurus took place.

Neither army had specifically chosen the battlefield. Indeed it wasn’t much of one, it was more of a chokepoint. To the north was the Metaurus river, running east to west. To the south was very hilly ground. The Roman force lined up facing east, on their left flank was the river and their left wing was composed of cavalry. Livius’ men made up most of the army here with Nero and his infantry on the right wing, presumably his calvalry had been added to that on the Roman left wing.

Hasdrubal’s army mirrored the Roman deployment, their cavalry was placed on the right flank, next to the river. In the centre he had his core infantry and elephants and on the left more infantry. The reason no cavalry was on the southern side of the battlefield was because of the hilly terrain. And it was here that Nero’s men watched as the battle ensued. Rome made early gains, perhaps through sheer numbers their cavalry was able to force the Carthaginian cavalry back. However in the centre the Carthaginian elephants were proving unusually effective, at least for the moment.

Nero took the initiative. Realising that his men on the right couldn’t get to the Carthaginian left wing because of the terrain he sent them behind the Roman line and out to the far left. This is where the cavalry had fought and because the Roman horse had forced the Carthaginian horse back there was a gap between the infantry and the river. Nero led his men through the gap and into the rear of the Carthaginian right.

This sort out flanking manouevre was death knell in most battles and certainly here. In the centre the elephants had routed and were killing men on either side. Realising the day was lost Hasdrubal rode to the centre of the line and to his death.

The Battle of the Metaurus was a turning point in the second Punic War. The story goes that Hannibal was informed of it when the head of his brother was thrown at a Carthaginian outpost in the south. Not just that but Carthaginian prisoners in chains were paraded there.

The message was clear and Hannibal must have realised that his position in Italy was crumbling. Perhaps it was this which led to Hannibal recording his achievements on a bronze tablet at a temple to Hera near Croton. He’d visited the temple after hearing that there was a solid gold column there and was intent on taking it until he had a dream where Hera appeared and warned him against doing so. The tablet was written in Punic and Greek, fustratingly Polybius actually saw it. I say frustratingly because all that Polybius took from it were the figures for the army size Hannibal had when he arrived in Italy. If only he had copied all of it, or at least more than a statistic, even though it’s a very useful one. Think of it, Hannibal’s account of things written by Hannibal.

Hannibals’ problems began to mount due to another Roman general, Scipio and the remaining years of the 2nd Punic War are writ large with the name Scipio hanging over them. Hannibal had actually faced both Scipio and his father and defeated both. Prior to the battle of the Trebia in 218 BC a small cavalry skirmish had resulted in the Roman consul called Scipio being seriously injured. As a result he was absent from the debacle at Trebia but won renown when he took a Roman force into the Iberian peninsual following this. The idea was to disrupt and break down the Carthaginian power base there.

It was his son, also called Scipio, though who was to cross paths with Hannibal in a few years as you’ll hear. The two had met earlier when Scipio survived the butchery at Cannae. Scipio was to later replace his father in Iberia leading the Roman fightback against Carthage there and earning impressive victories. There’s even a somewhat convenient anecdote in which Scipio jnr saved his father from certain death when when he was injured in that cavalry skirmish. But as I said, that’s a very convenient tale.

In 204 BC Scipio sailed with a now experienced force and landed near to Utica north Africa. Here he defeated the Numidian force set against him. The next target was Carthage, but Scipio, much like Hannibal after Cannae, knew that he lacked the needed resources to prosecute a siege. What resulted next was a drawn out negotation for a suspension of hostilities with a view for a treaty. This was eventually agreed and it bought time for Hannibal to be sent for.

In the autumn of 203 BC Hannibal landed with between 15-20,000 men near Hadrumentum, eventually wintering there. It was the first time that Hannibal had been on his native soil since he left it with his father for Iberia at the age of 9 in 237 BC. Now he was in his mid-40s and things had come full circle, it was he who was on the defensive. It was no longer a Carthaginian general on Roman soil, but a Roman general stamping his mark across Carthaginian lands.

In the spring of 202 BC the treaty was broken, although such treaties were invariably there until one party decided they were no longer required. With Hannibal and Scipio both in possession of armies it was just a matter of time until the two clashed. They did so at Zama in the summer or autumn of 202 BC. It was a clash of reputations and a decider to what the order of things would come to be.

The exact numbers on that day, as with many military encounters, are debated but Polybius gave a good overview of the troops deployed. Hannibal placed 80 elephants at the front of his line, behind these were the skirmishers and a line of infantry. Behind this was a second line. This reserve was formed of his most experienced troops. As mentioned earlier these were likely the 15-20,000 brought over from Italy. In total estimates give Hannibal as deploying 36,000 men in total in these two lines.

Numbers were particularly relevant in a key area for Hannibal – the cavalry. Prior to the battle most of his Numidian cavalry had deserted to Rome. Hannibal therefore had to make to with only 4,000 cavalry, formed of some remaining Numdian units but also Carthaginian horse.

The paucity in numbers and quality of cavalry available wouldn’t permit a favoured Hannibal tactic, namely to use the cavalry to deliver a devastating blow from flank or rear. Instead this cavalry would be used in a defensive capacity, because – as you’ll hear in a moment – Rome found itself in the rarest of situations, that of being able to better Hannibal’s cavalry.

With this deployment then we can make some assumptions about Hannibal’s plan. It relied on the elephants to break the Roman line and have the first line of infantry pour in and exhaust the Romans. The second line would then be sent in to finish the job.

Scipio’s deployment, as mentioned carried more cavalry. 6,000 including Numidian horse. In terms of infantry there would be the normal 3 lines. The hastati at the front, the heavier Pincipes behind them and the triarii, best thought of veteran spearmen as the third line. In total it’s estimated that Scipio had 24,000 men, with those 6,000 cavalry.

The battle opened with the standard skirmishing and then Hannibal set his elephants at the Roman line. However, Scipio seems to have planned for this and as the elephants hit the Roman first line the soldiers moved to create channels which the elephants ran down. They either passed through the line or were killed.

The Carthaginian first line then hit the Romans, albeit perhaps not in the confused and bruised state which they’d hoped. This first Roman line, the hastati was normally made of lighter infantry composed of the younger men eager to prove their worth. Rather than break it was the Hastati who repelled the Carthaginian line sending it scurrying back. Hannibal then played his last card, his second line composed of those soldiers who had been with him in Italy.

These were highly experienced and therefore highly dangerous – at least from a Roman perspective. As a response Scipio took the Principes and Triarii who were behind the Hastati and moved them either side of them. Both sides now had one long line carving bits out of each other. That was until the cavalry returned.

Early on the Roman cavalry had pushed the opposing cavalry off the battlefield. It now returned and fell on the exposed Carthaginian rear. A situation Rome had been all too familiar with was now horribly felt by Hannibal. His line crumpled and disintegrated. A Roman general had finally beat him and in a way which doesn’t feel far from the type of tactics he’d used.

This then is the end of the 2nd Punic War but as a postscript you might want to know what happened next. In short Carthage was forced into a treaty which looked to permanently shackle it financially. Hannibal continued for a time as a politician at Carthage. That was until he was exiled in 195 BC, Carthage hadn’t been as humbled as the Romans had hoped through the war indemnities imposed. Perhaps fearful of this Rome heaped pressure on Carthage to move Hannibal on. In his exile Hannibal worked as a military advisor and was courted by Kings in the eastern Mediterranean. His final years are less a history and more a collection of anecdotes but he was said to have died around 183 BC in Bithynia – modern day Northern Turkey. The story went that finally hounded by Roman forces he committed suicide. But again, nothing is fully certain.

And that brings me to a far more certain thing – the end of the episode. I hope you have enjoyed it and feel free to contact me to say hi. If you can rate or review please do – but more importantly until next time keep safe and stay well.